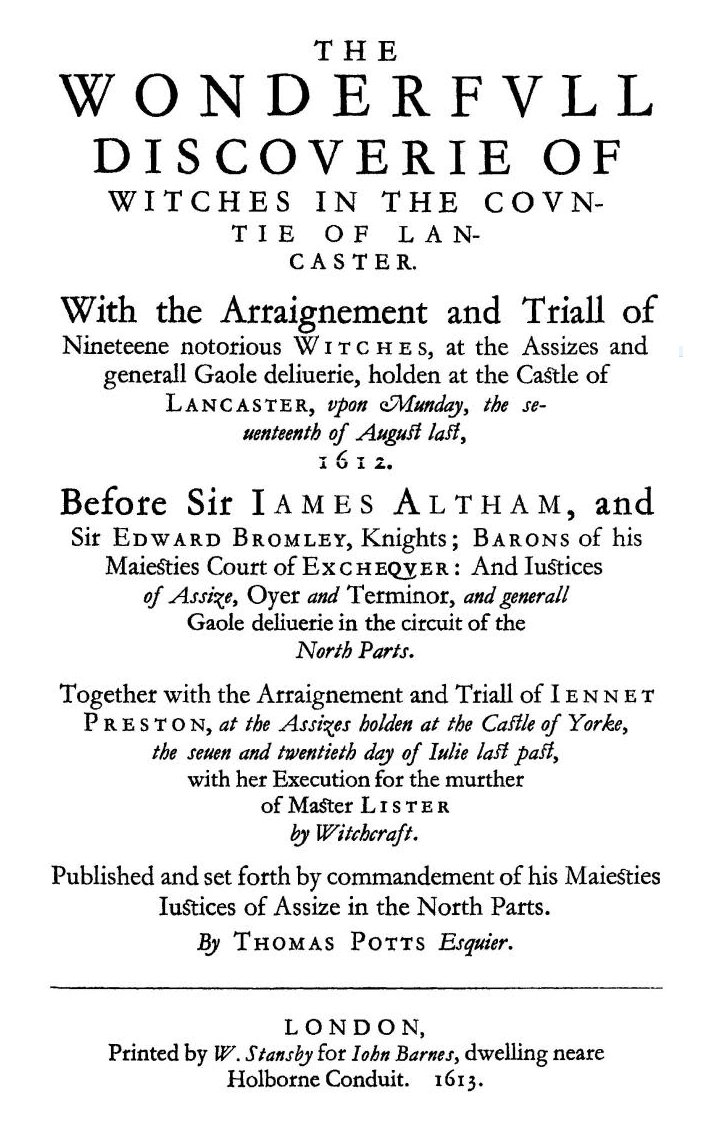

The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster is the account of a series of English witch trials that took place on 18–19 August 1612, commonly known as the Lancashire witch trials. Except for one trial held in York, they took place at Lancaster Assizes. Of the twenty men and women accused – among them the Pendle witches The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous witch trials in English history, and some of the best recorded of the 17th century. and the Samlesbury witches

The trials of the Pendle witches in 1612 are among the most famous witch trials in English history, and some of the best recorded of the 17th century. and the Samlesbury witches Three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. All three were acquitted. – eleven were found guilty and subsequently hanged; one was sentenced to stand in the pillory

Three women from the Lancashire village of Samlesbury accused by a 14-year-old girl, Grace Sowerbutts, of practising witchcraft. All three were acquitted. – eleven were found guilty and subsequently hanged; one was sentenced to stand in the pillory Device used to publicly humiliate those found guilty of minor offences., and the rest were acquitted.

Device used to publicly humiliate those found guilty of minor offences., and the rest were acquitted.

Thomas Potts, the clerk to the Lancaster Assizes, was ordered by the trial judges Sir James Altham and Sir Edward Bromley to write an account of the proceedings, making them some of the most famous and best recorded witch trials of the 17th century. Potts completed the work on 16 November 1612, and submitted it to the judges for review. Bromley revised and corrected the manuscript before its publication in 1613, declaring it to be “truly reported” and “fit and worthie to be published”.[1]

The historian Stephen Pumfrey has suggested that Bromley and Altham worked closely with Potts in the writing of The Wonderfull Discoverie “to manipulate the extraordinary records into an account that would protect and advance their careers”.[2] Potts’ book has been called the “clearest example of an account [of a witch trial] obviously published to display the shining efficiency and justice of the legal system”.[3] Although written as an apparently verbatim account, Potts was not reporting what had actually been said during the trials; he was reflecting what had happened.[4]

Thomas Potts

The author of The Wonderfull Discoverie, Thomas Potts, was brought up in the home of Thomas Knyvet,[5] the man who in 1605 had been credited with apprehending Guy Fawkes in his attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament, and thus saving the life of King James I.[6] At the time of writing his book, Potts was lodging in Chancery Lane, in London.[5]

Potts was employed as a clerk of the peace for the East Riding of Yorkshire in about 1610–11, and was an associate clerk on the northern assize circuit in the summer of 1612, when the Lancashire witch trials took place.[5] Although he had sufficient legal training to be able to advise Justices of the Peace, he had not received a university education. The normal career progression for a man in his position would have been a slow promotion to Clerk of the Assize, but only a few years after the publication of his book Potts began to receive “considerable royal favour”, suggesting that his account of the trials met with the King’s approval. King James was keenly interested in the breeding of hounds, and in 1615 Potts was rewarded with “the keepership of Skalme Park … for the breeding and training of hounds”. Three years later he was granted “the office of collecting the forfeitures on the laws concerning sewers, for twenty-one years”, a position that gave him the authority to appoint deputies.[7]

17th-century jurisprudence

Potts has been described as an “active and selective reporter”;[8] he omits significant details of court procedure in the early 17th-century English legal process, such as that all indictments were initially submitted to a grand jury, whose task was to decide whether there was a prima facie case against the accused before the prisoners were taken into the courtroom to be tried by the petty jury, the forerunner of the modern jury. The accused witches would not have been tried separately as Potts’ account suggests, but in groups.[9] Potts also represents written depositions as if they had been spoken in court, and he almost certainly “improved” Bromley’s speeches.[8]

Researcher Marion Gibson has suggested that “Potts and other pamphleteers have a different understanding of truthful reporting from modern scholars, subjugating what really happened to what ought to have happened.”[4] Nevertheless, Potts “seems to give a generally trustworthy, though not comprehensive, account of an Assize witchcraft trial, provided that the reader is constantly aware of his use of written material instead of verbatim reports”.[10]

Political background

The trials took place not quite seven years after the Gunpowder Plot Attempt in 1605 to assassinate King James I and re-establish a Catholic monarchy by blowing up the House of Lords. to blow up the House of Lords in an attempt to kill King James and the Protestant aristocracy had been foiled. It was alleged that the Pendle witches had hatched their own gunpowder plot to blow up Lancaster Castle, although historian Stephen Pumfrey has suggested that the “preposterous scheme” was invented by the examining magistrates.[11] It may therefore be significant that Potts dedicated The Wonderfull Discoverie to Thomas Knyvet and his wife Elizabeth; Knyvet was the man credited with apprehending Guy Fawkes and thus saving the King’s life.[6]

Attempt in 1605 to assassinate King James I and re-establish a Catholic monarchy by blowing up the House of Lords. to blow up the House of Lords in an attempt to kill King James and the Protestant aristocracy had been foiled. It was alleged that the Pendle witches had hatched their own gunpowder plot to blow up Lancaster Castle, although historian Stephen Pumfrey has suggested that the “preposterous scheme” was invented by the examining magistrates.[11] It may therefore be significant that Potts dedicated The Wonderfull Discoverie to Thomas Knyvet and his wife Elizabeth; Knyvet was the man credited with apprehending Guy Fawkes and thus saving the King’s life.[6]