Wikimedia Commons

Wife selling in England was a way of ending an unsatisfactory marriage by mutual agreement that probably began in the late 17th century, when divorce was a practical impossibility for all but the very wealthiest. After parading his wife with a halter around her neck, arm, or waist, a husband would publicly auction her to the highest bidder. Wife selling provides the backdrop for Thomas Hardy’s novel The Mayor of Casterbridge, in which the central character sells his wife at the beginning of the story, an act that haunts him for the rest of his life, and ultimately destroys him.

Although the custom had no basis in law and frequently resulted in prosecution, particularly from the mid-19th century onwards, the attitude of the authorities was equivocal. At least one early 19th-century magistrate is on record as stating that he did not believe he had the right to prevent wife sales, and there were cases of local Poor Law Commissioners forcing husbands to sell their wives, rather than having to maintain the family in workhouses.

Wife selling persisted in England in some form until the early 20th century; according to the jurist and historian James Bryce, writing in 1901, wife sales were still occasionally taking place during his time. In one of the last reported instances of a wife sale in England, a woman giving evidence in a Leeds police court in 1913 claimed that she had been sold to one of her husband’s workmates for £1.

Legal background

Wife selling in its “ritual form” appears to be an “invented custom” that originated at about the end of the 17th century,[2] although there is an account from 1302 of someone who “granted his wife by deed to another man”.[3] With the rise in popularity of newspapers, reports of the practice become more frequent in the second half of the 18th century.[4] In the words of 20th-century writer Courtney Kenny, the ritual was “a custom rooted sufficiently deeply to show that it was of no recent origin”.[5] Writing in 1901 on the subject of wife selling, James Bryce stated that there was “no trace at all in our [English] law of any such right”,[6] but he also observed that “everybody has heard of the odd habit of selling a wife, which still occasionally recurs among the humbler classes in England”.[7]

Marriage

Until the passing of the Marriage Act of 1753, a formal ceremony of marriage before a clergyman was not a legal requirement in England, and marriages were unregistered. All that was required was for both parties to agree to the union, so long as each had reached the legal age of consent,[8] which was 12 for girls and 14 for boys.[9] Women were completely subordinated to their husbands after marriage, the husband and wife becoming one legal entity, a legal status known as coverture. As the eminent English judge Sir William Blackstone wrote in 1753: “the very being, or legal existence of the woman, is suspended during the marriage, or at least is consolidated and incorporated into that of her husband: under whose wing, protection and cover, she performs everything”. Married women could not own property in their own right, and were indeed themselves the property of their husbands.[10] But Blackstone went on to observe that “even the disabilities the wife lies under are, for the most part, intended for her protection and benefit. So great a favourite is the female sex of the laws of England”.[3]

Separation

Five distinct methods of breaking up a marriage existed in the early modern period of English history. One was to sue in the ecclesiastical courts for separation from bed and board (a mensa et thoro), on the grounds of adultery or life-threatening cruelty, but it did not allow a remarriage. [11] From the 1550s, until the Matrimonial Causes Act became law in 1857, divorce in England was only possible, if at all, by the complex and costly procedure of a private Act of Parliament.[12] Although the divorce courts set up in the wake of the 1857 Act made the procedure considerably cheaper, divorce remained prohibitively expensive for the poorer members of society.[13][a]In his 1844 judgement against a bigamist, at Warwick Assizes, William Henry Maule described the process in detail.[14] “I will tell you what you ought to have done … You ought to have instructed your attorney to bring an action against the seducer of your wife for criminal conversation. That would have cost you about a hundred pounds. When you had obtained judgment for (though not necessarily actually recovered) substantial damages against him, you should have instructed your proctor to sue in the Ecclesiastical courts for a divorce a mensa et thoro. That would have cost you two hundred or three hundred pounds more. When you had obtained a divorce a mensa et thoro, you should have appeared by counsel before the House of Lords in order to obtain a private Act of Parliament for a divorce a vinculo matrimonii which would have rendered you free and legally competent to marry the person whom you have taken on yourself to marry with no such sanction. The Bill might possibly have been opposed in all its stages in both Houses of Parliament, and together you would have had to spend about a thousand or twelve hundred pounds. You will probably tell me that you have never had a thousand farthings of your own in the world; but, prisoner, that makes no difference. Sitting here as an English Judge, it is my duty to tell you that this is not a country in which there is one law for the rich and one for the poor. You will be imprisoned for one day. Since you have been in custody since the commencement of the Assizes you are free to leave.”[15] This affirmation later contributed to the passing of the 1857 Act. An alternative was to obtain a “private separation”, an agreement negotiated between both spouses, embodied in a deed of separation drawn up by a conveyancer. Desertion or elopement was also possible, whereby the wife was forced out of the family home, or the husband simply set up a new home with his mistress.[11] Finally, the less popular notion of wife selling was an alternative but illegitimate method of ending a marriage.[16] The Laws Respecting Women, As They Regard Their Natural Rights (1777) observed that, for the poor, wife selling was viewed as a “method of dissolving marriage”, when “a husband and wife find themselves heartily tired of each other, and agree to part, if the man has a mind to authenticate the intended separation by making it a matter of public notoriety”.[15]

Although some 19th-century wives objected, records of 18th-century women resisting their sales are non-existent. With no financial resources, and no skills on which to trade, for many women a sale was the only way out of an unhappy marriage.[17] Indeed, the wife is sometimes reported as having insisted on the sale. A wife sold in Wenlock Market for 2s. 6d. in 1830 was quite determined that the transaction should go ahead, despite her husband’s last-minute misgivings: “‘e [the husband] turned shy, and tried to get out of the business, but Mattie mad’ un stick to it. ‘Er flipt her apern in ‘er gude man’s face, and said, ‘Let be yer rogue. I wull be sold. I wants a change’.”[18]

For the husband, the sale released him from his marital duties, including any financial responsibility for his wife.[17] For the purchaser, who was often the wife’s lover, the transaction freed him from the threat of a legal action for criminal conversation, a claim by the husband for restitution of damage to his property, in this case his wife.[19]

Sale

It is unclear when the ritualised custom of selling a wife by public auction began, but it seems likely to have been some time towards the end of the 17th century. In November 1692 “John, ye son of Nathan Whitehouse, of Tipton, sold his wife to Mr. Bracegirdle”, although the manner of the sale is unrecorded. In 1696, Thomas Heath Maultster was fined for “cohabiteing in an unlawful manner with the wife of George ffuller of Chinner … haueing bought her of her husband at 2d.q. the pound”,[20] and ordered by the peculiar court at Thame to perform public penance, but between 1690 and 1750 only eight other cases are recorded in England.[21] In an Oxford case of 1789 wife selling is described as “the vulgar form of Divorce lately adopted”, suggesting that even if it was by then established in some parts of the country it was only slowly spreading to others.[22] It persisted in some form until the early 20th century, although by then in “an advanced state of decomposition”.[23]

In most reports the sale was announced in advance, perhaps by advertisement in a local newspaper. It usually took the form of an auction, often at a local market, to which the wife would be led by a halter (usually of rope but sometimes of ribbon)[5] around her neck, or arm.[24] Often the purchaser was arranged in advance, and the sale was a form of symbolic separation and remarriage, as in a case from Maidstone, where in January 1815 John Osborne planned to sell his wife at the local market. However, as no market was held that day, the sale took place instead at “the sign of ‘The Coal-barge,’ in Earl Street”, where “in a very regular manner”, his wife and child were sold for £1 to a man named William Serjeant. In July the same year a wife was brought to Smithfield market by coach, and sold for fifty guineas and a horse. Once the sale was complete, “the lady, with her new lord and master, mounted a handsome curricle which was in waiting for them, and drove off, seemingly nothing loath to go.” At another sale in September 1815, at Staines market, “only three shillings and four pence were offered for the lot, no one choosing to contend with the bidder, for the fair object, whose merits could only be appreciated by those who knew them. This the purchaser could boast, from a long and intimate acquaintance.”[25]

Although the initiative was usually the husband’s, the wife had to agree to the sale. An 1824 report from Manchester says that “after several biddings she [the wife] was knocked down for 5s; but not liking the purchaser, she was put up again for 3s and a quart of ale”.[26] Frequently the wife was already living with her new partner.[27] In one case in 1804 a London shopkeeper found his wife in bed with a stranger to him, who, following an altercation, offered to purchase the wife. The shopkeeper agreed, and in this instance the sale may have been an acceptable method of resolving the situation. However, the sale was sometimes spontaneous, and the wife could find herself the subject of bids from total strangers.[28] In March 1766, a carpenter from Southwark sold his wife “in a fit of conjugal indifference at the alehouse”. Once sober, the man asked his wife to return, and after she refused he hanged himself. A domestic fight might sometimes precede the sale of a wife, but in most recorded cases the intent was to end a marriage in a way that gave it the legitimacy of a divorce.[29] In some cases the wife arranged for her own sale, and even provided the money for her agent to buy her out of her marriage, such as an 1822 case in Plymouth.[30]

Such “divorces” were not always permanent. In 1826 John Turton sold his wife Mary to William Kaye at Emley CrossRural village in the South Pennine fringe, midway between Hudddersfield and Wakefield. for five shillings. But after Kaye’s death she returned to her husband, and the couple remained together for the next thirty years.[31]

Mid-19th century

| The Duke of Chandos, while staying at a small country inn, saw the ostler beating his wife in a most cruel manner; he interfered and literally bought her for half a crown. She was a young and pretty woman; the Duke had her educated; and on the husband’s death he married her. On her death-bed, she had her whole household assembled, told them her history, and drew from it a touching moral of reliance on Providence; as from the most wretched situation, she had been suddenly raised to one of the greatest prosperity; she entreated their forgiveness if at any time she had given needless offence, and then dismissed them with gifts; dying almost in the very act.[32] — The Gentleman’s MagazineMonthly compendium of the best news, essays and information from the daily and weekly newspapers, published from 1731 until 1914., 1832 |

It was believed during the mid-19th century that wife selling was restricted to the lowest levels of labourers, especially to those living in remote rural areas, but an analysis of the occupations of husbands and purchasers reveals that the custom was strongest in “proto-industrial” communities. Of the 158 cases in which occupation can be established, the largest group (19) was involved in the livestock or transport trades, fourteen worked in the building trade, five were blacksmiths, four were chimney-sweeps, and two were described as gentlemen, suggesting that wife selling was not simply a peasant custom. The most high-profile case was that of Henry Brydges, 2nd Duke of Chandos, who is reported to have bought his second wife from an ostler in about 1740.[33]

Prices paid for wives varied considerably, from a high of £100 plus £25 each for her two children in a sale of 1865 (equivalent to about £13,200 in 2018)[34] to a low of a glass of ale, or even free. The lowest amount of money exchanged was three farthings (three-quarters of one penny), but the usual price seems to have been between 2s. 6d. and 5 shillings.[34] According to authors Wade Mansell and Belinda Meteyard, money seems usually to have been a secondary consideration;[4] the more important factor was that the sale was seen by many as legally binding, despite it having no basis in law. Some of the new couples bigamously married,[29] but the attitude of officialdom towards wife selling was equivocal.[4] Rural clergy and magistrates knew of the custom, but seemed uncertain of its legitimacy, or chose to turn a blind eye. Entries have been found in baptismal registers, such as this example from Perleigh in Essex, dated 1782: “Amie Daughter of Moses Stebbing by a bought wife delivered to him in a Halter”.[35] A jury in Lincolnshire ruled in 1784 that a man who had sold his wife had no right to reclaim her from her purchaser, thus endorsing the validity of the transaction.[36] In 1819 a magistrate who attempted to prevent a sale at Ashbourne, Derby, but was pelted and driven away by the crowd, later commented:

In some cases, such as that of Henry Cook in 1814, the Poor Law authorities forced the husband to sell his wife rather than have to maintain her and her child in the Effingham workhouse. She was taken to Croydon market and sold for one shilling, the parish paying for the cost of the journey and a “wedding dinner”.[38]

Venue

| It is this day agreed on between John Parsons, of the parish of Midsummer Norton, in the county of Somerset, clothworker, and John Tooker, of the same place, gentleman, that the said John Parsons, for and in consideration of the sum of six pounds and six shillings in hand paid to the said John Parsons, doth sell, assign, and set over unto the said John Tooker, Ann Parsons, wife of the said John Parsons; with all right, property, claim, services, and demands whatsoever, that he, the said John Parsons, shall have in or to the said Ann Parsons, for and during the term of the natural life of her, the said Ann Parsons. In witness whereof I, the said John Parsons, have set my hand the day and year first above written.[5] — Bill of sale for a wife, contained within a petition of 1768 |

By choosing a market as the location for the sale, the couple ensured a large audience, which made their separation a widely witnessed fact.[40] The use of the halter was symbolic; after the sale, it was handed to the purchaser as a signal that the transaction was concluded,[4] and in some instances, those involved would often attempt further to legitimate the sale by forcing the winning bidder to sign a contract, recognising that the seller had no further liability for his wife. In 1735, a successful wife sale in St Clements was announced by the common cryer,[b]A common cryer was a person whose responsibility it was to make public announcements on behalf of his employer. who wandered the streets ensuring that local traders were aware of the former husband’s intention not to honour “any debts she should contract”. The same point was made in an advertisement placed in the Ipswich Journal in 1789: “no person or persons to intrust her with my name … for she is no longer my right”.[39] Those involved in such sales sometimes attempted to legalise the transaction, as demonstrated by a bill of sale for a wife, preserved in the British Museum.[c]MSS. 32,084 The bill is contained in a petition presented to a Somerset Justice of the Peace in 1758, by a wife who about 18 months earlier had been sold by her husband for £6 6s “for the support of his extravagancy”. The petition does not object to the sale, but complains that the husband returned three months later to demand more money from his wife and her new “husband”.[5]

In Sussex, inns and public houses were a regular venue for wife-selling, and alcohol often formed part of the payment. For example, when a man sold his wife at the Shoulder of Mutton and Cucumber in Yapton in 1898, the purchaser paid 7s. 6d. (£40 in 2018)[34] and 1 imperial quart (1.1 l) of beer. A sale a century earlier in Brighton involved “eight pots of beer” and seven shillings (£30 in 2018);[34] and in Ninfield in 1790, a man who swapped his wife at the village inn for half a pint of gin changed his mind and bought her back later.[40]

Public wife sales[d]Private sales have not been counted.[41] were sometimes attended by huge crowds. An 1806 sale in Hull was postponed “owing to the crowd which such an extraordinary occurrence had gathered together”, suggesting that wife sales were relatively rare events, and therefore popular. Estimates of the frequency of the ritual usually number about 300 between 1780 and 1850, relatively insignificant compared to the instances of desertion, which in the Victorian era numbered in the tens of thousands.[42]

Distribution and symbolism

Wikimedia Commons

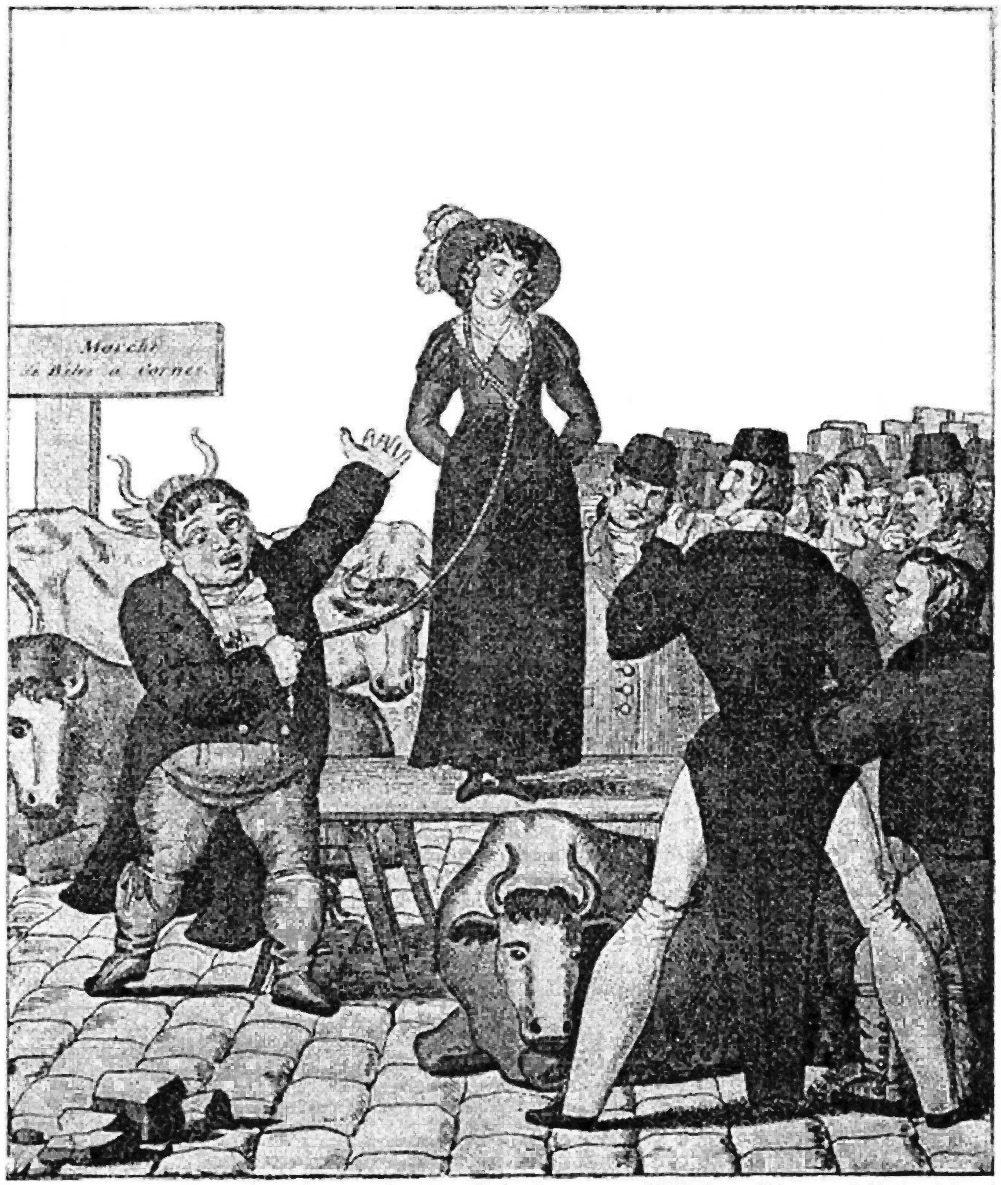

Wife selling appears to have been widespread throughout England, but relatively rare in neighbouring Wales, where only a few cases were reported, and in Scotland where only one has been discovered. The English county with the highest number of cases between 1760 and 1880 was Yorkshire, with forty-four, considerably more than the nineteen reported for Middlesex and London during the same period, despite the French caricature of Milord John Bull “booted and spurred, in [London’s] Smithfield Market, crying ‘à quinze livres ma femme!‘ [£15 for my wife], while Milady stood haltered in a pen”.[43]

In his account, Wives for Sale, author Samuel Pyeatt Menefee collected 387 incidents of wife selling, the last of which occurred in the early 20th century.[45] Historian E. P. Thompson considered many of Menefee’s cases to be “vague and dubious”, and that some double-counting had taken place, but he nevertheless agreed that about three hundred were authentic, which when combined with his own research resulted in about four hundred reported cases.[44]

Menefee argued that the ritual mirrored that of a livestock sale – the symbolic meaning of the halter; wives were even occasionally valued by weight, just like livestock. Although the halter was considered central to the “legitimacy” of the sale, Thompson has suggested that Menefee may have misunderstood the social context of the transaction. Markets were favoured not because livestock was traded there, but because they offered a public venue where the separation of husband and wife could be witnessed. Sales often took place at fairs, in front of public houses, or local landmarks such as the obelisk at Preston (1817), or Bolton’s gas pillar[e]The gas pillar was a large cast iron vase erected in the early 19th century, in Bolton’s market square, atop which was a gas lamp. The whole structure was about 30 feet (9 m) tall. (1835), where crowds could be expected to gather.[45]

There were very few reported sales of husbands, and from a modern perspective, selling a wife like a chattel is degrading, even when considered as a form of divorce.[46] Nevertheless, most contemporary reports hint at the women’s independence and sexual vitality: “The women are described as ‘fine-looking’, ‘buxom’, ‘of good appearance’, ‘a comely-looking country girl’, or as ‘enjoying the fun and frolic heartily’&thinsp”.[47]

Along with other English customs, settlers arriving in the American colonies during the late 17th and early 18th centuries took with them the practice of wife selling, and the belief in its legitimacy as a way of ending a marriage. In 1645 “The P’ticular Court” of Hartford, Connecticut, reported the case of Baggett Egleston, who was fined 20 shillings for “bequething his wyfe to a young man”. The Boston Evening-Post reported on 15 March 1736 an argument between two men “and a certain woman, each one claiming her as his Wife, but so it was that one of them had actually disposed of his Right in her to the other for Fifteen Shillings”. The purchaser had, apparently, refused to pay in full, and had attempted to return “his” wife. He was given the outstanding sum by two generous bystanders, and paid the husband – who promptly “gave the Woman a modest Salute wishing her well, and his Brother Sterling much Joy of his Bargain.”[48] An account in 1781 of a William Collings of South Carolina records that he sold his wife for “two dollars and half [a] dozen bowls of grogg”.[49]

Changing attitudes

| On Friday a butcher exposed his wife to Sale in Smithfield Market, near the Ram Inn, with a halter about her neck, and one about her waist, which tied her to a railing, when a hog-driver was the happy purchaser, who gave the husband three guineas and a crown for his departed rib. Pity it is, there is no stop put to such depraved conduct in the lower order of people.[50] — The Times, July 1797 |

Towards the end of the 18th century, some hostility towards wife selling began to manifest itself amongst the general population. One sale in 1756 in Dublin was interrupted by a group of women who “rescued” the wife, following which the husband was given a mock trial and placed in the stocksDevice used to publicly humiliate those found guilty of minor offences. until early the next morning. In about 1777, a wife sale at Carmarthenshire produced in the crowd “a great silence”, and “a feeling of uneasiness in the gathering”.[51] When a labourer offered his wife for sale on Smithfield market in 1806, “the public became incensed at the husband, and would have severely punished him for his brutality, but for the interference of some officers of the police.”[36]

Reports of wife selling rose from two per decade in the 1750s, to a peak of fifty in the 1820s and 1830s. As the number of cases increased so did opposition to the practice. It became seen as one of a number of popular customs that the social elite believed it their duty to abolish, and women protested that it represented “a threat and insult to their sex”.[36] JPs in Quarter Sessions became more active in punishing those involved in wife selling, and some test cases in the central law courts confirmed the illegality of the practice.[52] Newspaper accounts were often disparaging: “a most disgusting and disgraceful scene” was the description in a report of 1832,[53] but it was not until the 1840s that the number of cases of wife selling began to decline significantly. Thompson discovered 121 published reports of wife sales between 1800 and 1840, as compared to 55 between 1840 and 1880.[43]

Wikimedia Commons

Lord Chief Justice William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield, considered wife sales to be a conspiracy to commit adultery, but few of those reported in the newspapers led to prosecutions in court.[4] The Times reported one such case in 1818, in which a man was indicted for selling his wife at Leominster market, for 2s. 6d.[54] In 1825 a man named Johnson was charged with “having sung a song in the streets describing the merits of his wife, for the purpose of selling her to the highest bidder at Smithfield.” Such songs were not unique; in about 1842 John Ashton wrote “Sale of a Wife”.[55][f]Thank you, sir, thank you, said the bold auctioneer,

Going for ten—is there nobody here

Will bid any more? Is this not a bad job?

Going! Going! I say—she is gone for ten bob.[56]

The arresting officer claimed that the man had gathered a “crowd of all sorts of vagabonds together, who appeared to listen to his ditty, but were in fact, collected to pick pockets.” The defendant, however, replied that he had “not the most distant idea of selling his wife, who was, poor creature, at home with her hungry children, while he was endeavouring to earn a bit of bread for them by the strength of his lungs.” He had also printed copies of the song, and the story of a wife sale, to earn money. Before releasing him, the Lord Mayor, judging the case, cautioned Johnson that the practice could not be allowed, and must not be repeated.[57] In 1833 the sale of a woman was reported at Epping. She was sold for 2s. 6d., with a duty of 6d. Once sober, and placed before the Justices of the Peace, the husband claimed that he had been forced into marriage by the parish authorities, and had “never since lived with her, and that she had lived in open adultery with the man Bradley, by whom she had been purchased”. He was imprisoned for “having deserted his wife”.[58]

The return of a wife after eighteen years results in Michael Henchard’s downfall in Thomas Hardy’s novel The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886). A bad-tempered, impulsive and cruel husband, feeling burdened by his wife, Henchard sells her to a stranger for five guineas. He becomes a successful businessman and rises to the position of mayor, but the return of his wife many years later prompts his fall back into penury.[59] The custom was also referred to in the 19th-century French play, Le Marché de Londres. Commenting on the drama and contemporary French attitudes on the custom, in 1846 the writer Angus B. Reach complained: “They reckon up a long and visionary list of our failings [… They] would as readily give up their belief in the geographical and physical existence of London, as in the astounding fact that in England a husband sells his wife exactly as he sells his horse or his dog.”[60] Such complaints were still commonplace nearly 20 years later; in The Book of Days (1864), author Robert Chambers wrote about a case of wife selling in 1832, and noted that “the occasional instances of wife-sale, while remarked by ourselves with little beyond a passing smile, have made a deep impression on our continental neighbours, [who] constantly cite it as an evidence of our low civilisation.”[61] Embarrassed by the practice, a legal handbook of 1853 enabled English judges to dismiss wife selling as a myth: “It is a vulgar error that a husband can get rid of his wife by selling her in the open market with a halter round her neck. Such an act on his part would be severely punished by the local magistrate.”[62] Originally published in 1869, Burn’s Justice of the Peace and Parish Officer states that “publicly selling or buying a wife is clearly an indictable offence … And many prosecutions against husbands for selling, and others for buying, have recently been sustained, and imprisonment for six months inflicted”.[63]

Another form of wife selling was by deed of conveyance. Although initially much less common than sale by auction, the practice became more widespread after the 1850s, as popular opinion turned against the market sale of a wife.[64] The issue of the commonly perceived legitimacy of wife selling was also brought to the government. In 1881, Home Secretary William Harcourt was asked to comment on an incident in Sheffield, in which a man sold his wife for a quart of beer. Harcourt replied: “no impression exists anywhere in England that the selling of wives is legitimate”, and “that no such practice as wife selling exists”,[65] but as late as 1889, a member of the Salvation Army sold his wife for a shilling in Hucknall Torkard, Nottinghamshire, and subsequently led her by the halter to her buyer’s house, the last case in which the use of a halter is mentioned.[64] The most recent case of an English wife sale was reported in 1913, when a woman giving evidence in a Leeds police court during a maintenance case claimed that her husband had sold her to one of his workmates for £1, equivalent to about £90.[g]Comparing the value of £1 in 1913 with 2017 using the retail price index[66] The manner of her sale is unrecorded.[23]

Notes

| a | In his 1844 judgement against a bigamist, at Warwick Assizes, William Henry Maule described the process in detail.[14] “I will tell you what you ought to have done … You ought to have instructed your attorney to bring an action against the seducer of your wife for criminal conversation. That would have cost you about a hundred pounds. When you had obtained judgment for (though not necessarily actually recovered) substantial damages against him, you should have instructed your proctor to sue in the Ecclesiastical courts for a divorce a mensa et thoro. That would have cost you two hundred or three hundred pounds more. When you had obtained a divorce a mensa et thoro, you should have appeared by counsel before the House of Lords in order to obtain a private Act of Parliament for a divorce a vinculo matrimonii which would have rendered you free and legally competent to marry the person whom you have taken on yourself to marry with no such sanction. The Bill might possibly have been opposed in all its stages in both Houses of Parliament, and together you would have had to spend about a thousand or twelve hundred pounds. You will probably tell me that you have never had a thousand farthings of your own in the world; but, prisoner, that makes no difference. Sitting here as an English Judge, it is my duty to tell you that this is not a country in which there is one law for the rich and one for the poor. You will be imprisoned for one day. Since you have been in custody since the commencement of the Assizes you are free to leave.”[15] |

|---|---|

| b | A common cryer was a person whose responsibility it was to make public announcements on behalf of his employer. |

| c | MSS. 32,084 |

| d | Private sales have not been counted.[41] |

| e | The gas pillar was a large cast iron vase erected in the early 19th century, in Bolton’s market square, atop which was a gas lamp. The whole structure was about 30 feet (9 m) tall. |

| f | Thank you, sir, thank you, said the bold auctioneer, Going for ten—is there nobody here Will bid any more? Is this not a bad job? Going! Going! I say—she is gone for ten bob.[56] |

| g | Comparing the value of £1 in 1913 with 2017 using the retail price index[66] |

References

- p. 163

- p. 820

- p. 88

- pp. 819–820

- p. 819

- pp. 816–817

- pp. 12–13

- p. 141

- p. 144

- p. 15

- p. 215

- pp. 217–218

- p. 462

- p. 122

- p. 76

- p. 412

- pp. 408–409

- pp. 215–216

- pp. 216–217

- p. 433

- p. 428

- pp. 216–217

- p. 216

- pp. 440–441

- p. 132

- pp. 413–414

- p. 415

- p. 451

- pp. 86–87

- p. 223

- p. 51

- p. 218

- p. 65

- pp. 409–412

- pp. 147–148

- p. 409

- p. 408

- p. 418

- pp. 458–459

- p. 461

- pp. 224–225

- p. 131

- p. 217

- p. 416

- p. 3

- pp. 95–97

- p. 487

- pp. 146–147

- p. 1025

- p. 455