British Museum

Agnes Sampson was a Scottish cunning woman, healer and midwife. She was already being held by the Haddington Presbytery under suspicion of witchcraft when she was named as an associate by Geillis DuncanYoung Scottish maidservant suspected of witchcraft by her employer in November 1590. After being tortured, the initial testimony she gave led to the start of the North Berwick witch trials. Young Scottish maidservant suspected of witchcraft by her employer in November 1590. After being tortured, the initial testimony she gave led to the start of the North Berwick witch trials. , who was facing similar charges in a nearby parish. Transported to Edinburgh, Agnes was further interrogated, then eventually tried and convicted of witchcraft on 27 January 1591 as part of the North Berwick witch trialsSeries of Scottish witch trials held between 1590 and 1593 ; she was strangled and her body burned on Edinburgh’s Castle Hill the following day.

Agnes was a central figure in what became a major and significant series of trials; King James VI took a personal interest in the ensuing events after allegations were made the coven of witches of which she was a part was plotting against his life. The pamphlet, Newes from Scotland1591 pamphlet describing the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, detailing the confessions given by the accused witches before the King., printed in London while the trials were taking place but produced after she had been executed, gave an account of her interrogations and confessions; the narrative was sensationalised and some of the content is omitted from official records.

Modern-day scholars consider that from her recorded examinations of early December 1590, the inquisitors’ initial questioning of a cunning woman takes the route of transforming her into a witch.

Background

A resident in a little village named Nether Keith just south of Haddington, East Lothian, Agnes Sampson, Samsoune or Samson, was commonly known as the wise wife of Keith or the “wyse wyff of Keyth”.[1][2][3][a]In Scotland and England during the sixteenth century spelling was haphazard leading to many words, places and names having several variations. Modern-day texts often use an anglicised version.[4] Records do not precisely indicate her age; historian Peter Maxwell-Stuart describes her as middle-aged,[2] whereas other scholars, including Brian Levack, refer to her as elderly.[5] She was a widow with children; following the death of her husband she was left in straitened circumstances.[6]

Coached in some of the black arts by her father,[7] midwifery, healing, making predictions and other skills associated with being a cunning woman formed the basis of Agnes’s career since at least 1585. She usually worked in the local area around Haddington; those availing themselves of her services came from a wide socio-economic status, ranging from minor gentry like Lady Edmiston, Lady Kilbaberton and Lady Roslin, through to servants, poor people as well as the spouses of skippers and the sheriff of Haddington.[8]

Matronly and solemn in character, her attempts at healing were not always productive with varying levels of success. Powders were administered to ease the discomfort of her customers when they were giving birth; she chanted prayers to determine whether someone’s malaise would be fatal – if she was able to recite a bastardised form of the Apostles’ Creed without faltering her patient would recover whereas any hesitation in her rendering was indicative of death.[7]

Agnes advocated the use of eggs soaked in vinegar and iris as methods to aid curing illness; a whisky embrocation applied to a patient’s back was another of her recommendations as a healing process.[9] Wax figurines were deployed as part of her repertoire when she was approached for assistance by Barbara NapierWoman accused of witchcraft and conspiracy to murder during the North Berwick witch trials.; similar devices were given to Euphame MacCalzeanWealthy Scottish heiress and member of the gentry convicted of witchcraft. A key figure in the North Berwick witchcraft trials of 1590–1591. as a means to help elicit the death of her client’s father-in-law.[7]

Witchcraft accusations

An accusation of witchcraft was made against Agnes in early 1589; the Presbytery at Haddington investigated but when asked about it by the Synod in April, it reported it could find no grounds to substantiate the complaint. On 16 September, the Presbytery was again taken to task for not dealing with the matter; it was raised again on 5 May 1590 with the Synod being informed two days later that it was ongoing.[10] The Synod appointed two members of the Dalkeith Presbytery, Adam Johnston and George Ramsay, to ensure assistance was given to the local ministers and elders undertaking the investigation.[11]

Six months later, in November 1590, a young maidservant, Geillis DuncanYoung Scottish maidservant suspected of witchcraft by her employer in November 1590. After being tortured, the initial testimony she gave led to the start of the North Berwick witch trials. Young Scottish maidservant suspected of witchcraft by her employer in November 1590. After being tortured, the initial testimony she gave led to the start of the North Berwick witch trials. , was questioned by her employer as he suspected she was involved in witchcraft. After being tortured Geillis confessed and went on to name several others including Agnes,[2] triggering what was to become known as the North Berwick witch trials, the first major Scottish witch-hunt and the inaugural large witchcraft trial under criminal law.[12][13] Agnes had not initially been detained during the previous springtime enquiries, remaining at liberty until after Halloween;[14] by November however she was incarcerated in the tolbooth at Haddington awaiting the outcome of the earlier investigation.[15] She was transported to Edinburgh for interrogation concerning the maidservant’s claims. The first statement by Agnes in Edinburgh, made in the days before 4 or 5 December, is a transcription of her answers to a series of specific questions put to her by her inquisitors.[16]

Confessions

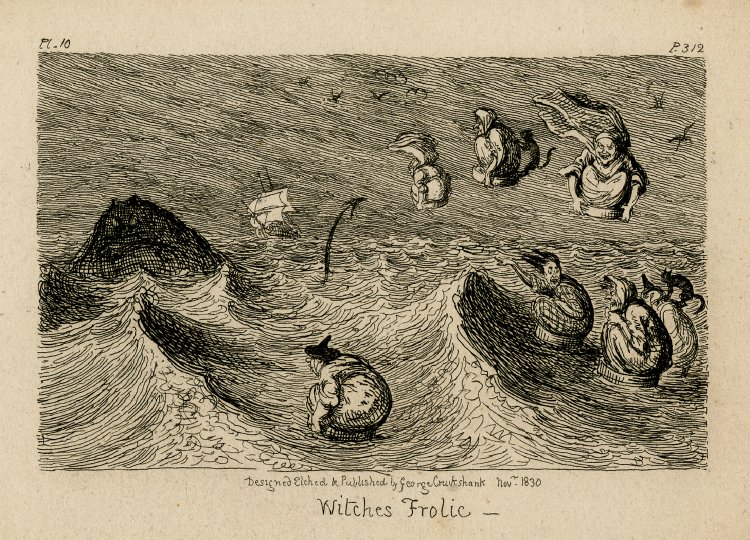

Initially Agnes described being involved in a Devil’s convention held at Bara two years earlier.[15][b]Bara or Baro was a small parish in East Lothian; in 1702 it conjoined with the adjacent parish of Garvald.[17] Naming several other attendees including Kate Gray[c]This name is sometimes given as Kate Graw or Katherine Gray.[15] and Davie Steel, both of whom had been executed between late 1588 and the end of 1590,[15][d]Both Kate Gray and Davie Steel were later named as attendees at the Halloween North Berwick convention in 1590 so their execution dates can be narrowed down to between 31 October and 4-5 December 1590; no documentation or details of local trials for them have yet been found.[15] she went on to recap details of her participation in the large convention of male and female witches held at North Berwick kirk on Halloween in 1590. Agnes, who travelled to the meeting on horseback, said the Devil was present; attired in a black hat and robe, he checked the names of attendees on a register who then paid homage to him by performing an obscene kissRitual of a witch paying homage to the Devil by kissing his genitals, anus or feet. .[18] The convention drew to a close after they had all danced and been entertained by Geillis playing a Jew’s harp.[19][e]A Jew’s harp is also known as a Jew’s trump or, especially in Scotland, as a trump.[20] Agnes admitted being present at several sabbaths and, coupled with the testimony given in statements from other accused persons, attended at least eight meetings.[21]

During the course of her early examinations, Agnes fleetingly touched on conjuring poor weather at sea to thwart the King’s attempts to bring his new bride to Scotland. When she went on to elaborate that she had been informed by the Devil that ministers were plotting against James, the King became directly involved in the questioning.[22]

Among the deeds Agnes confessed to was the excavation of bodies for use in magical practices.[23] The powders she used in rituals were made from the joints of the corpses, using instructions she had received from the Devil. At the North Berwick convention, she participated in opening three graves then removing finger joints, the nose and toes from the bodies; other corpses had been dug up in Newton Kirk.[24]

Execution

At her trial on 27 January 1591,[25] Agnes confessed to 58 of the 102 accusations laid against her.[26] Declared guilty, she was transported to Castle Hill, Edinburgh, the following day where she was strangled and her body burned.[25] The costs recorded for her execution totalled £6 8s 10d Scots.[27][f]Prior to 1707 Scotland had its own currency, the pounds Scots; up until 1603 the exchange rate with the English pound sterling fluctuated as the rate was based on the bullion content of the coins.[28]

Newes from Scotland

In late 1591, the pamphlet Newes from Scotland1591 pamphlet describing the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, detailing the confessions given by the accused witches before the King.1591 pamphlet describing the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, detailing the confessions given by the accused witches before the King. was produced.[29] Tailored specifically for an English audience,[30] it recounts facets of the North Berwick witch trials,[31] some of which are not reflected in the official documentation.[32] The narrator describes Agnes taking the King aside during his interrogation of her; she reportedly reveals to James words he exchanged in an intimate moment with his bride as evidence she is genuine about her magical powers.[33] Maxwell-Stuart speculates that as Agnes knew one of the King’s servants, who may have been in attendance in the royal newly weds bedchamber, the servant may have relayed to her the snippet of conversation she was able to tell the King to prove she was truthful.[34] This event is not recounted in any other documentation but scholars Lawrence Normand and Gareth Roberts note that “it seems unlikely that anyone would risk inventing it”[33] while historian Julian Goodare suggests that the existence of the conversation “need not be taken literally” bearing in mind sections of the pamphlet are fanciful.[35]

People suspected of witchcraft were regularly subjected to informal and illegal cruelty and torture at the behest of their interrogators; by necessity official documentation does not reflect the practice. Newes relays lurid details concerning the Devil’s mark being discovered on Agnes’s “privaties”.[36][g]The Devil’s mark is usually recorded as being found on the arm, neck or shoulders of those accused of witchcraft in Scotland; it is more commonly alluded to as secreted in more discrete areas of the body in Continental cases.[37]

Modern interpretations

The cases involved in the North Berwick trials demonstrates the changing perspective, particularly of the elite classes, to witchcraft.[38] The accusations concerning Agnes chanting Catholic prayers while performing magical deeds reflects unease on the part of her questioners rather than indicating her religious denomination as no documentation survives to support her Catholicism.[39]

An unusual item within her confessions was the excavation of bodies to use in magical practices, which is uncommon among Scottish witchcraft records; it does however appear in a handful of other cases, including the confessions of Isobel GowdieScottish woman accused of witchcraft in 1662 and probably executed, whose detailed testimony provides one of the most comprehensive insights into European witchcraft folklore at the end of the era of witch-hunts. from Auldearn in 1662.[23]

Scholars Normand and Roberts note that Agnes’s examination and confession on 4 and 5 December shows the inquisitors transforming a “cunning woman into a witch”.[40]

Notes

| a | In Scotland and England during the sixteenth century spelling was haphazard leading to many words, places and names having several variations. Modern-day texts often use an anglicised version.[4] |

|---|---|

| b | Bara or Baro was a small parish in East Lothian; in 1702 it conjoined with the adjacent parish of Garvald.[17] |

| c | This name is sometimes given as Kate Graw or Katherine Gray.[15] |

| d | Both Kate Gray and Davie Steel were later named as attendees at the Halloween North Berwick convention in 1590 so their execution dates can be narrowed down to between 31 October and 4-5 December 1590; no documentation or details of local trials for them have yet been found.[15] |

| e | A Jew’s harp is also known as a Jew’s trump or, especially in Scotland, as a trump.[20] |

| f | Prior to 1707 Scotland had its own currency, the pounds Scots; up until 1603 the exchange rate with the English pound sterling fluctuated as the rate was based on the bullion content of the coins.[28] |

| g | The Devil’s mark is usually recorded as being found on the arm, neck or shoulders of those accused of witchcraft in Scotland; it is more commonly alluded to as secreted in more discrete areas of the body in Continental cases.[37] |