Wikimedia Commons

The North Berwick witch trials took place in the Lothian area of Edinburgh between 1590 and 1593. The first arrests occurred in November and December 1590, but the precise number of those detained is uncertain. As the examinations and then trials gained momentum, associations extending back to events surrounding the marriage of King James VI and Anne of Denmark began to be revealed.[1] The historian Malcolm Gaskill has described the North Berwick witch trials as “treason cloaked as witchcraft”.[2]

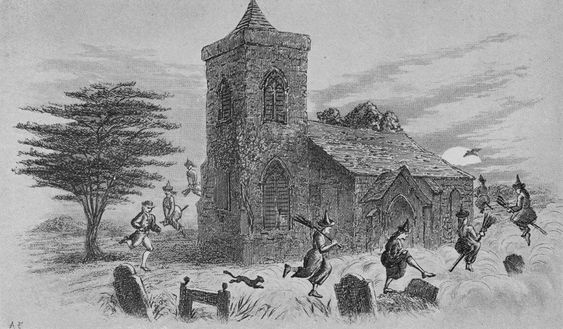

None of those convicted or associated with the events were residents of North Berwick. The appellation simply refers to the largest alleged gathering of the witches on Halloween 1590, at the Kirk yard in the village.

Political background

King James VI of Scotland reigned over a country where in the second half of the sixteenth century all levels of society, from peasants through to the highest ranks of the nobility, had a firm belief in witchcraft.[3] Scotland was also going through a crisis of religious upheaval and reformation, with relationships between Catholics and Protestants tense across all strata of society.[4] Protestants were recasting the rudimentary beliefs held in particular by the lower classes as evil, by characterising them as superstition and witchcraft, thus providing a means to eliminate such beliefs in a move towards social and moral rehabilitation.[5] The academic Stuart Clark suggests that was an integral component at the core of the process of securing the changes over to their form of Christianity.[6] From 1586 advocates of extreme Presbyterianism, such as the minister James Carmichael, began returning to Scotland to support the views of Andrew Melville, the leader of the Presbyterians.[7]

Scotland during the reign of King James was beset by political turbulence and political unease.[8] The overall plight of the kingdom was exacerbated by poverty among the lower classes, famine caused by recurring harvest failures, and several outbreaks of plague.[9][a]Plague epidemics occurred in: 1568–1569; 1574; an especially protracted outbreak during 1584–1588; and 1597–1599.[9][10]

The King’s first cousin, Frances Stewart, fifth Earl of Bothwell,[b]Francis Stewart Hepburn (1562–1612);[11] he is sometimes designated as the first Earl of Bothwell. was three years older than the King,[12][c]At the time of the North Berwick trials Bothwell and the King were in their twenties.[12] highly educated, wealthy and well-connected. From a noted family of Protestants, Bothwell had strong political ambitions and influence,[13] and was recognised by the King as his heir in 1576.[14] James frequently placed the earl in positions of trust, but Bothwell could be particularly troublesome and volatile;[15] he is described by the modern-day scholar Peter Maxwell-Stuart as “the bane of James’s life and a person whose sinister influence on contemporary Scottish politics is difficult to under-estimate.”[16]

Royal marriage

In June 1589 agreement was reached that the King would marry the fourteen-year-old Danish princess, Anne of Denmark. The union was seen as politically and dynastically advantageous, as Denmark, which already had trade ties with Scotland, was also a Protestant country.[17] After a proxy marriage on 20 August 1589 in Copenhagen, at the beginning of September the bride attempted to join her groom in Scotland but her sea voyage was marred by storms and leaking vessels so the flotilla was forced to seek refuge in Norway. Later in the month the convoy of ships twice endeavoured to make the three-day journey but were again thwarted by storms and leaks.[18][19]

Scotland was also being ravaged by fierce storms during that autumn. A ferryboat transporting wedding presents for the King and his bride sank while attempting to cross the Forth between Burntisland and Leith; all of the consignment was lost and forty people on board died.[1] Among the fatalities was the courtier Janet Kennedy, whom the King had assigned to be one of his new wife’s ladies-in-waiting.[20][d]Janet Kennedy Melville (d. 1589), who is sometimes referred to as Jane, (Normand and Roberts use Jean Kennedy[21]) had been one of the attendants of Mary, Queen of Scots, James’s mother, and was present at her execution two years earlier in 1587, having served her for almost twenty years. Janet’s husband, Sir Andrew Melville, was the master of the King’s household.[20] Sir Andrew was one of the prosecutors in a case against William Downie, Robert Linkup and John Watson on 14 January 1590. The three Leith men were facing a charge of slaughter in respect of the lives lost in the ferryboat’s sinking, as they controlled a boat that ran into the sunken vessel.[22]

Despite the persistent bad weather the King decided that a fleet should be sent from Scotland to Denmark to fetch Anne and bring her to him. The Earl of Bothwell was initially instructed to undertake the journey, but the Chancellor, Lord Maitland,[e]John Maitland, 1st Lord Maitland of Thirlestane (1543 – 3 October 1595), appointed as vice chancellor in 1586 rising to chancellor from 1587 until 1595[23] declared Bothwell’s quote as excessive and advised James to make the journey himself.[24] Although the weather was still inclement, James heeded the advice given and set off for Norway on 21 October in a ship laden with provisions of food and wine accompanied by the chancellor, leaving mainly Bothwell to govern in their absence.[f]The King appointed Bothwell as deputy to the fifteen-year-old Duke of Lennox while Robert Bruce, an Edinburgh minister, provided guidance based on opinions from the Kirk.[25] The King met Anne in Oslo, and after a marriage ceremony there in November, the royal party continued on to Denmark, where they remained until early 1590.[24] The royal entourage departed from Copenhagen on 21 April but the voyage was again beleaguered by inclement weather and storms while at sea; the convoy did not dock at Leith until 1 May.[26]

Trials in Denmark

While James was in Denmark several Danish women were rumoured to have conjured up the storms by using witchcraft.[27] The allegations emanated from charges brought by Peder Munk, the admiral responsible for the fleet of ships used in the aborted voyages of the princess, against Christofer Valkendorf, the Governor of Copenhagen. Valkendorf, with whom Munk had a long-standing feud, was in control of the finances for maintaining the seaworthiness of the Danish Royal Navy. The admiral alleged that the ships were in a poor state of repair, rendering them unfit to cope with the ferocity of the weather encountered;[28][29] Valkendorf countered the accusation claiming the difficulties were the result of witchcraft,[26] a common scenario in Scandinavian countries where tumultuous seas were frequently put down to curses uttered by witches.[30]

After being subjected to torture, a confession of involvement in raising the storms by witchcraft was made by a local woman, Anna Koldings, who was already incarcerated as a suspected witch. Commonly known as “the Devil’s mother”, Koldings admitted that, working with several others, the group was seeking to stop the fleet arriving at its destination.[g]Koldings gave her interrogators the names of five associates.[31] Confessions from two other women have survived in the official records. Little of the trial documentation is extant, but a series of trials took place commencing in April 1590. About thirteen people, including a mayor’s spouse, were executed; one woman hanged herself while imprisoned.[26][32] A vague suggestion began to circulate that there might have been an element of collusion with Scottish witches,[30] although it was not until late in July that the rumours reached Scotland.[33]

Return to Scotland

On its return to Scotland the royal party was preoccupied by organising Anne’s coronation and entertaining the Danish contingent, made up of 223 people including Peder Munk, to daily banquets.[34] Routine investigations, trials and executions for witchcraft were occurring in various parts of Scotland as far afield as Aberdeen and Ross-shire as well as East Lothian and Edinburgh.[35] The King was kept occupied until late autumn, showing little interest in witchcraft other than being mildly intrigued.[36] Earlier his curiosity had been sufficiently piqued in Aberdeen during April 1589 for him to ask to see Marion MacIngaroch, who had reportedly cured a man.[37] He also interviewed a woman from Lübeck, Germany, allegedly a witch, who had arrived in Leith to see Queen Anne in July 1590. The woman claimed to have a prophecy for the King about future “noble deeds” he was going to perform, although his willingness to grant her an audience stemmed not from an interest in sorcery but from his curiosity about the introductory letter she carried.[38]

The Earl of Bothwell’s stewardship of the country had been relatively smooth during the King’s absence.[25] But following a brief period of amicable relations after the royal entourage returned to Scotland, Bothwell was soon falling in and out of favour with James; several arguments and disputes occurred between them between May and the end of October, with the King becoming increasingly distrustful of, and irritated by, the earl.[39]

Suspicion of witchcraft

In November 1590, David Seton,[h]Alternative spellings of his name, for example Seaton, are sometimes used in sources. the magistrate at Tranent, became suspicious that one of his servants, Geillis DuncanYoung Scottish maidservant suspected of witchcraft by her employer in November 1590. After being tortured, the initial testimony she gave led to the start of the North Berwick witch trials. , was involved in the use of witchcraft, as she had suddenly gained a reputation as a healer and was frequently absent from her quarters at night.[40] The magistrate, together with his son also named David, were known locally as keen witch-hunters.[10] After being tortured, Geillis started to confess then proceeded to implicate others during later interrogations. These included Agnes SampsonScottish midwife, cunning woman and healer; central figure in the North Berwick witch trials., an elderly midwife and healer from Nether Keith, near Haddington and Doctor FianSchool teacher convicted of witchcraft in 1590, a central figure in the North Berwick witch trialsSchool teacher convicted of witchcraft in 1590, a central figure in the North Berwick witch trials (alias John Cunningham), a schoolmaster from Prestonpans.[1][40][i]Doctor was the term used for a schoolmaster.[40]

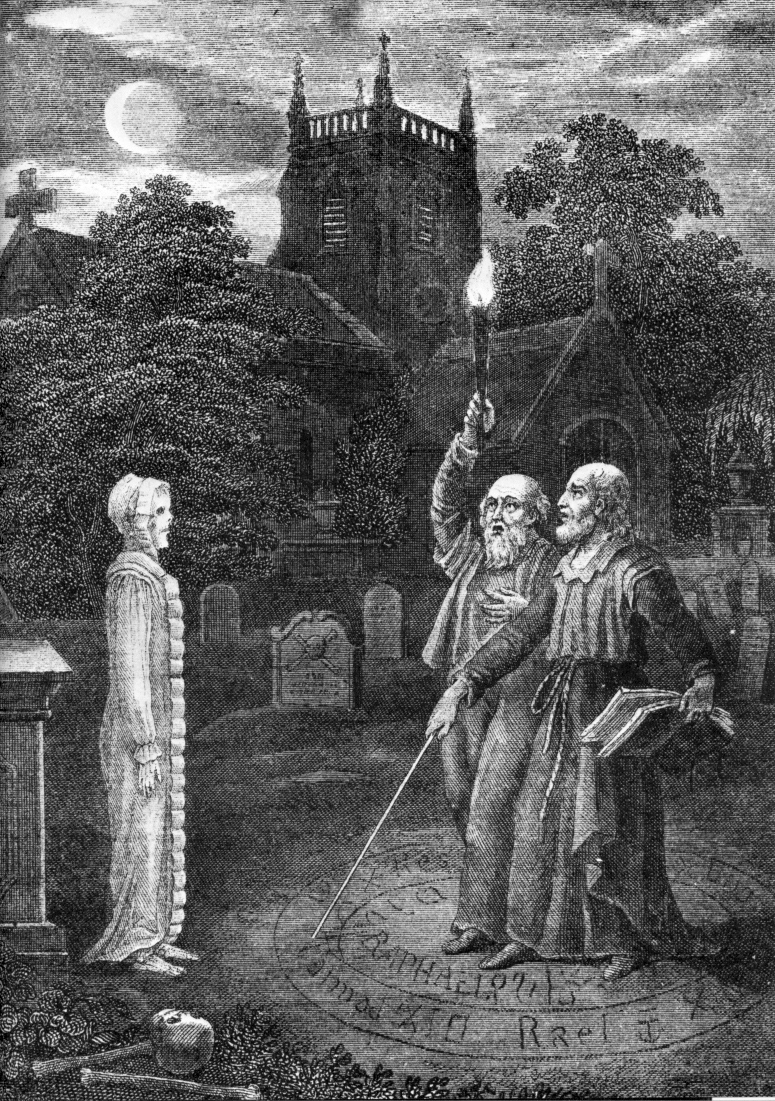

In the typical style of an emerging extensive witch-hunt, there was a ripple or wave effect as other affiliated people were implicated.[40] By 11 November 1590, Ritchie GrahamSorcerer, necromancer and wizard. Executed on the last day of February 1592 as part of the North Berwick witch trials, he was an associate of Francis Stewart, fifth Earl of Bothwell. , who had a well-established and long-standing reputation among the aristocracy as a magician and necromancer

Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive., was detained in the Edinburgh tolbooth.[41] Initially other individuals compromised were, like Agnes and Fian, of a low social status. Very quickly however, members of a higher social stature began to be incriminated. Women like Barbara NapierWoman accused of witchcraft and conspiracy to murder during the North Berwick witch trials., a member of Edinburgh’s high society, and Euphame MacCalzeanWealthy Scottish heiress and member of the gentry convicted of witchcraft. A key figure in the North Berwick witchcraft trials of 1590–1591., a prominent heiress and part of the city’s legal dynasty, both of whom had prior involvement with Geillis and Agnes, were named.[42]

Early proceedings

Art UK

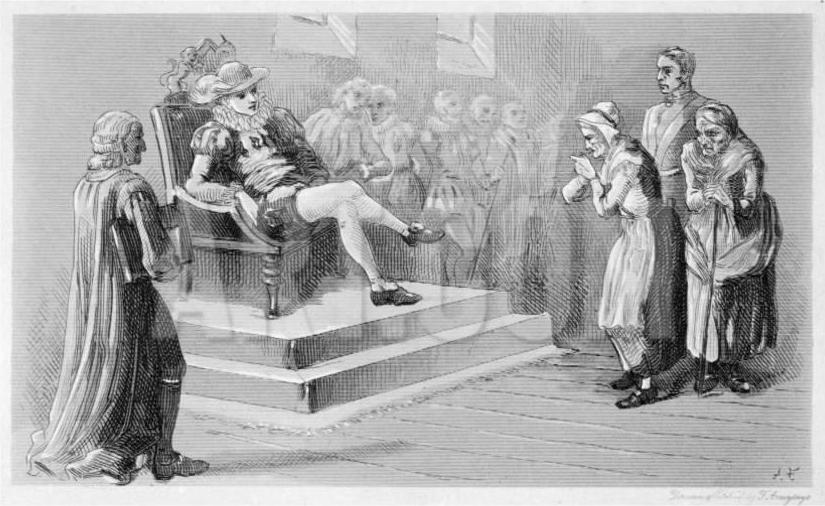

The King displayed a passing interest in the early proceedings against Geillis and Agnes.[43] After he was informed Agnes had confessed that Geillis had played a Jew’s harp at a witches convention in the North Berwick kirk on Halloween 1590, he insisted the young maidservant be brought to play the instrument for him.[44] In an audience with the monarch, Agnes described her involvement in several exploits. Among these deeds were trying to cause him harm by casting a spell on a scrap of linen he had used; the summoning of stormy weather by magic to adversely upset the royal couples’ sailings; and her attendance with several others at witches meetings, the most important of which was held at North Berwick. The indictment levied against Agnes, like that of Fian (who was also interrogated by the King[37]), did not deeply worry James as the escapades were not those of high conspirators or seriously treasonable;[45] any qualms the King may have had regarding threats against his safety from those of the lower classes like Agnes were easily addressed by judiciary process then disposed of by execution.[46] Fian was pronounced guilty of various points of witchcraft at his trial on 26 December 1590;[47] Agnes was tried and declared guilty on 27 January 1591, then strangled and her body burned the following day.[48][j]All dates in this article are given in the New Style (Gregorian), but at the time Scotland was still using the Julian calendar, so some sources give 16 December 1590 as Fian’s date of execution. Both the Julian and Gregorian calendars were in use throughout Europe between 1582 and 1752.[49] By this time, approximately forty people were in prison awaiting trial with around another eight already executed.[50]

Contemporary sources indicate that investigations were ongoing, although official documents covering the start of February until 4 May 1591 have not survived.[51] The Earl of Bothwell was mentioned fleetingly during the early interrogations, although his name did not feature in Agnes or Fian’s dittays.[50] The correspondence of Robert Bowes, the English diplomat who was Ambassador for Scotland from 1577 until 1583,[52] shows earnest moves to further connect Bothwell’s involvement in treasonable acts of witchcraft during April after statements taken from Ritchie Graham implicated him to a greater extent.[53][54][k]In 1593 Bothwell claimed the conspirators working with Ritchie Graham against him included nobles such as the Earl of Morton, the Chancellor, the King’s advocate and others.[54] Graham claimed that Bothwell was at the heart of plots to harm the King, that the pair had several meetings to plan how it could be accomplished, and they sought the help and advice of other witches. He elaborated that after the unsuccessful attempts to sink the King and his new bride’s vessels with storms, poisoning was the group’s next failed endeavour; later they attempted to elicit the monarch’s demise by bewitching a wax effigy of him.[55]

The earl was imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle by the Privy Council on 15 April,[56][57] the same date on which, according to Bowes, another of the accused witches, Robert GriersonNamed by several accused of witchcraft during the North Berwick witch trials, Grierson died whilst being tortured during his interrogation., died owing to the severity of torture inflicted on him.[58] As the official documents began to be manipulated to form an eloquent account of treasonable acts committed by the group using witchcraft, particularly that of Bothwell’s deeper incrimination, the King began to take the matter seriously, worrying that his life might be at risk.[57]

High society trials

While the Earl of Bothwell was incarcerated, trials of members of the Edinburgh elite began.[59] Barbara Napier, a known acquaintance of the earl,[10] was tried on 8 May 1591;[60] she was found guilty of consulting with witches – namely Ritchie Graham and Agnes Sampson[57] – but exonerated on the charge of being present at a witches convention.[61] The jury was at first reluctant to apply the death sentence to her,[62] but did so on 10 May.[63] The King was unwilling to accept the court findings, and wrote to the jury members insisting a guilty verdict be returned for all charges.[61] They were ordered to an audience with James on 7 June; he berated them at length, emphasising the error of their judgement.[64] It was at the trial of Barbara’s jurors that the allegations she was party to a conspiracy to harm the King unfolded; this had not been alleged at her own trial.[65] She gained a stay of execution by claiming that she was pregnant,[63] but her ultimate fate is unclear. She was known to be alive but probably incarcerated in June 1591,[66] but she may have been executed later that year, together with five others.[10][66]

In the meantime, charges of conspiring treason with Barbara Napier and other witches were laid against the Earl of Bothwell;[67] he vehemently denied the claims, threatening dire retribution against those making the assertions.[56] The King’s suspicions regarding the earl intensified,[68] but Bothwell remained popular among some members of the nobility, so any action against him would be difficult to enforce.[69]

A close affiliate of the earl, Euphame MacCalzean[70] was in prison by 7 May, and being interrogated about letters and food she had sent to others held in custody.[53] Sworn statements had been taken during January from several people, including her servants, who claimed she was present at witch gatherings held at Acheson’s Haven and North Berwick the previous year. Donald Robson, Janet Stratton and Geillis Duncan alleged Euphame handled a waxen image of King James at the conventions, while she hinted that a new sovereign would be the Earl of Bothwell.[71] Euphame’s connections with Bothwell were leading her towards facing charges of treasonable witchcraft.[53] The focus of the indictment against her was clearly articulated as it was headed with: “Dilated of certain treasonable conspiracies, enterprised by witchcraft, to have destroyed our sovereign lord’s person and bereft His Majesty of his life.”[72][l]In this instance “enterprised” is interpreted as “attempted” by Normand and Roberts.[73]

Euphame’s trial started on 9 June 1591;[74] six eminent advocates argued in her defence for several days.[75] On 12 June the panel of notable landed gentry declared her guilty of ten of the twenty-eight charges listed in her indictment including that of “being a well-known witch”.[74][76] She was also convicted on two counts of attending meetings of witches.[76] The sentence of death by being burned alive and the forfeiture of all her estates was handed down on 15 June.[74] Her execution was delayed however, as like Barbara Napier she tried to claim pregnancy to stave off the death penalty.[74] Euphame was nevertheless transported to Castle Hill, tied to a stake and burned alive on 25 June 1591, still maintaining her innocence.[77]

Proclamation

During the days of Euphame’s trial and execution, two other events took place. The King interviewed Janet KennedyJanet or Jonet Kennedy from Redden or Reydon was a Scottish visionary involved in the North Berwick witch trials of 1590–1593., the witch of Redden, sometimes given as Reydon, on 14 June. She confirmed Ritchie Graham’s implications against Bothwell[67][m]Maxwell-Stuart refers to her as a witch from Redden but does not supply a name.[67] and, according to the scholars Lawrence Normand and Gareth Roberts, her deposition provides “the unique moment in the records when it is insinuated that Bothwell actually attended a convention.”[78] A week later, three days before Euphame’s execution, the Earl of Bothwell escaped captivity during the night of 21/22 June through a hole cut into the roof of his room, claiming that there was “no hope of lyffe lefte to hyme”.[79][n]Some academics, for instance Edward J. Cowan, quote 22 June;[68] Normand and Roberts state 2am on 21 June.[80] He had been informed hours beforehand that the King was considering releasing him on bail, but only on condition that he agreed to adhere strictly to certain conditions, which included his immediate banishment overseas.[81]

On the day Euphame was burnt alive at the stake, a royal proclamation was issued against Bothwell.[79] The edict alleged that the fugitive employed witchcraft for political motives, and that he plotted with God’s enemies to subvert true religion in a conspiratorial manner involving treason against King and country.[82] Among other assertions, it stated that Bothwell consulted witches and toyed with necromancy; consulting with witches had been made a capital offence by the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563Series of Acts passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland making witchcraft a secular offence punishable by death..[83] The decree deemed that his escape from custody before he could be tried signified his guilt.[79] Thus declared an outlaw and traitor, the earl’s properties were forfeit.[84]

Aftermath

Recantations and revocations

On 4 July, less than a fortnight after Euphame’s execution, Donald Robson and Janet Stratton withdrew their assertions that she had attended the witch meetings or had anything to do with the waxed effigy. Robson further clarified that he had not seen, nor had any knowledge of Euphame, until he encountered her when making his previous statement.[85] Similarly, six months later, at the time of their execution on 4 December 1591, Geillis, and another of the alleged witches named in her first statement, Bessie Thomson, made lengthy statements retracting their accusations against Euphame and Barbara Napier of being involved in witchcraft.[86] When questioned as to why they lied in their confessions, both declared they were forced into it by David Seton, his son and others whose names were not revealed.[87]

After Patrick MacCalzean – Euphame’s husband – paid 5,000 merks to recover the lands,[88] King James eventually reversed the forfeiture of Euphame’s property and estates to the Crown by passing an Act in June 1592, returning her lands to her daughters.[89] The Cliftonhall estate was specifically excluded from the properties reinstated; after the forfeiture the sovereign had gifted it to Sir James Sandilands and it remained in his ownership.[90][o]Sir James Sandilands, a favourite of King James,[90] was the brother of the Laird of Pumperston’s fiancée, Mary Sandilands, by marriage as the pair had wed on 15 July 1586 despite Euphame’s efforts to prevent it. Maxwell-Stuart suggests the King may have felt allowing the Sandilands to retain possession of the estate was “a form of poetic justice”.[91][92]

Earl of Bothwell

In the months following the earl’s escape from custody, he remained at large freely roaming the areas of Lothian and the Borders despite attempts to capture him.[11] His escapades became legendary. Stories – some fact interspersed with fictional accounts – circulated about sightings of him ranging from the Hebrides, Caithness as well as the Merse.[93][p]The Merse is an archaic term used to describe Berwickshire particularly the area encompassing about 20 miles (32 km) west of Kelso.[94] English correspondents likened him to a latter day Robin Hood;[95][96] the twenty-first century academic Rob Macpherson describes the political situation in Scotland during that time as a “period of high farce”.[11]

The King and Queen were in residence at Falkland Palace on 28 June 1592 when the earl made an unsuccessful attack on it, backed by four hundred armed men.[97] Face to face confrontations also took place between the two adversaries. The earl accosted James and Anne in their Holyrood chambers in December 1591, leading to the execution of his seven accomplices and a reward being posted for his capture. On 24 July 1593 Bothwell again managed entry to the King’s bedroom. Various versions of this encounter from contemporaries exist, but all have the same final result of a calming in the feud between the pair.[98] The King yielded to his cousin’s request to be tried for the witchcraft charges made against him in April 1591; the trial took place on 10 August 1593.[99] Ritchie Graham had been executed more than a year earlier, but his testimony was used as a key component in the charges against the earl.[100] At the time of his execution Graham continued to insist the statements he made about the earl’s involvement in a conspiracy against the King were true.[79]

The verdict, rendered by an assize of seventeen noblemen,[q]The panel was made up of two earls, seven lords and eight barons.[101] was to acquit Bothwell on the charge of attempting to use witchcraft for regicide.[99] It was reached during a period when the earl had increasingly strong political support in contrast to the falling level given to the monarch.[102] The balance of support swayed back to the King within a few weeks;[69] Bothwell joined forces with the papist earls, but by March 1595, the King had secured agreement from the Edinburgh presbytery that the earl be excommunicated.[103] Exiled in late March or early April,[r]Some sources quote March[11] whereas others give April[103] for when he left Scotland he moved around Europe,[103] continuing to plot against the King. Hatching schemes to mount attacks on Scotland or England that never came to fruition, there were also rumours that he dabbled in necromancy. His health was poor in later years, and he died destitute in Naples in 1612.[103][104]

Contemporary publications

Newes from Scotland

Survey of Scottish Witchcraft

In late 1591, at the height of the witch-hunt in North Berwick, Newes from Scotland1591 pamphlet describing the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, detailing the confessions given by the accused witches before the King., the earliest Scottish or English printed document dedicated exclusively to covering witchcraft in Scotland, was published.[105] Tailored specifically for an English audience,[57] the unsigned manuscripts are likely to have been written by James Carmichael, the minister of Haddington, who was involved in examining the accused witches.[106][107] Details of the initial events leading up to the trials together with how each of the suspected witches were discovered and captured are documented, ending with the execution of John Fian.[108]

Described by the modern-day historians Lizanne Henderson and Edward Cowan as including “a good dose of titillation and gruesome detail”,[109] it provided the first descriptions of the osculum infameRitual of a witch paying homage to the Devil by kissing his genitals, anus or feet. , also known as the kiss of shame or the obscene kiss, to an English audience.[110] Lurid details of the violent torture inflicted – and the instruments used – on the accused, but not recorded in official documents, are catalogued.[111] Despite being published after suspicion turned towards the Earl of Bothwell,[112] he is not mentioned anywhere within the text.[33]

Daemonologie

King James started to draft a manuscript for a witchcraft treatise in the wake of the North Berwick events.[113] First published in 1597,[114] Daemonologie incorporated details from 1590–1591 together with information derived from the Aberdeen witch-hunt of 1597.[113] Portions of the text closely resemble the pre-trial examinations and dittays collected during the North Berwick panic.[115] Later editions were produced, including in 1603 when he ascended to the English throne;[114] a 1924 edition includes a copy of Newes from Scotland.[116]

The compendium of three books covers magic, sorcery and witchcraft, and in the third book, the different types of spirits.[117] Giving a clear articulation of the King’s beliefs regarding witches,[113] it takes the form of a conversation between Philomathes and Epistemon; the latter answers questions raised by the former.[118] Two methods were advocated to be used for witch-findingMethods used to identify witches. : pricking the suspects body to find the Devil’s mark, and swimming. Pricking was common practice in Scotland both before and after the publication of Daemonologie, but swimming was rarely used.[119][s]The popularity of detecting witches by pricking led to professionals, such as John KincaidProfessional witch-finder or pricker of witches based in Tranent, East Lothian. , being commonplace in the next two centuries; swimming is only recorded as used once in Scotland, in Aberdeen during 1597, whereas it was common practice in England.[120]

Modern interpretations

None of those convicted or associated with the events were residents of North Berwick;[10] the designation of North Berwick witch trials or alternatively witches is applied as an umbrella term as the largest gathering of the witches, on Halloween 1590, was described in the confessions as being held in the Kirk yard at the village.[121] Some historians expand the appellation to include the outbreak in 1597 as the King became involved then too but the later prosecutions are a separate entity.[122][123]

Writing in the mid-twentieth century on events surrounding the witchcraft accusations and trials of North Berwick, the scholar Helen Stafford observed: “Thus the whole episode remains shrouded in doubts and uncertainties. The fragmentary records excite curiosity and speculation and offer no resolution.”[124] Echoing that sentiment in 1973, historian Christina Larner commented: “Whether there was a genuine conspiracy to kill the king, a scare that snowballed, or a government conspiracy to incriminate the Earl of Bothwell, it is now impossible to say.”[125][t]Quoted by Maxwell-Stuart in The British Witch, referenced to the posthumous publication of Larner’s essays in 1984; the original quote is from the chapter ‘James VI and I and Witchcraft’ appearing on page 79, by Larner within The Reign of James VI and I, published in 1973

Larner, a highly respected historian,[u]Julian Goodare describes Larner (1933 – 27 April 1983) as “the most important scholar that Scottish witchcraft had ever had”,[126] an opinion shared by other academics. published two books: A Sourcebook of Scottish Witchcraft (1977) and Enemies of God (1981);[127] her greatly acclaimed and influential work led to a lull in scholarly research as she had produced such a broad, in-depth coverage of the topic.[128] Investigations were however reinvigorated in the last decade of the twentieth century; new resources allowed opportunities to build on and refine Larner’s work as well as approaching the topic from a different perspective.[126] The scrutiny since the 1990s has identified some facets and long held assumptions that require revision.[129]

Twenty-first-century academics Jenny Wormald and Maxwell-Stuart independently reached the conclusion that King James did not bring continental type witch theory back from Denmark as originally suggested.[130] Wormald demonstrates that David Seton had knowledge of the demonic pact before James became involved, and highlights the incidence of diabolism in the earlier 1572 case of Janet BoymanScottish woman found guilty and executed for witchcraft and associating with fairies..[131] John Knox may have been familiar with the demonic pact as early as 1556.[132] Other aspects, such as “general commission for trying witches”[133] and the role of nobility, lairds and the church are still being debated.[129]

Maxwell-Stuart offers a theory that the descriptions given of the Devil at the conventions may have a basis in the interrogators desire to depict a similarity to the black gowns and hats sported by Catholic priests.[134] Fellow academic Joyce Miller notes that post-reformation priests dressed in the same fashion.[135] According to Normand and Roberts, the examinations of those suspected of witchcraft influenced King James’s opinions while the nobility managed to shape the confessions into narratives of collusion and treason to suit their own political agendas.[3]

Political manoeuvring may also be the basis for speculation concerning the role of another member of elite women, Jean Lyon, the Countess of AngusScottish countess named in North Berwick witch trials as consulting with witches. She was connected to several of the accused witches, including Barbara Napier and Euphame MacCalzean,[136] and was mentioned in the depositions given by Agnes Sampson in January 1591 and again in Janet Stratton’s examination later that month.[137] Archibald Douglas, the eighth Earl of Angus, the countess’s second husband, died on 4/5 August 1588,[v]The ODNB entry for the eighth earl gives 4 August[138] aged thirty-three; witchcraft was blamed for his illness and death.[139] The countess’s name continued to appear, including in the list of accusations levelled at Barbara during her trial in May. Despite this evidence that she consulted witches, Jean was never interrogated or arrested.[140] The academic Victoria Carr suggests that James “entertained the idea of Jean’s guilt for a few months.”[141] After 7 June, however, no further connections to Jean are made until the earl’s trial in 1593; she lived until the first decade of the 17th-century.[142]

In the view of historian Brian Levack, “politicization of witchcraft was James’s main contribution to Scottish witch-hunting”.[122]

Notes

| a | Plague epidemics occurred in: 1568–1569; 1574; an especially protracted outbreak during 1584–1588; and 1597–1599.[9][10] |

|---|---|

| b | Francis Stewart Hepburn (1562–1612);[11] he is sometimes designated as the first Earl of Bothwell. |

| c | At the time of the North Berwick trials Bothwell and the King were in their twenties.[12] |

| d | Janet Kennedy Melville (d. 1589), who is sometimes referred to as Jane, (Normand and Roberts use Jean Kennedy[21]) had been one of the attendants of Mary, Queen of Scots, James’s mother, and was present at her execution two years earlier in 1587, having served her for almost twenty years. Janet’s husband, Sir Andrew Melville, was the master of the King’s household.[20] Sir Andrew was one of the prosecutors in a case against William Downie, Robert Linkup and John Watson on 14 January 1590. The three Leith men were facing a charge of slaughter in respect of the lives lost in the ferryboat’s sinking, as they controlled a boat that ran into the sunken vessel.[22] |

| e | John Maitland, 1st Lord Maitland of Thirlestane (1543 – 3 October 1595), appointed as vice chancellor in 1586 rising to chancellor from 1587 until 1595[23] |

| f | The King appointed Bothwell as deputy to the fifteen-year-old Duke of Lennox while Robert Bruce, an Edinburgh minister, provided guidance based on opinions from the Kirk.[25] |

| g | Koldings gave her interrogators the names of five associates.[31] |

| h | Alternative spellings of his name, for example Seaton, are sometimes used in sources. |

| i | Doctor was the term used for a schoolmaster.[40] |

| j | All dates in this article are given in the New Style (Gregorian), but at the time Scotland was still using the Julian calendar, so some sources give 16 December 1590 as Fian’s date of execution. Both the Julian and Gregorian calendars were in use throughout Europe between 1582 and 1752.[49] |

| k | In 1593 Bothwell claimed the conspirators working with Ritchie Graham against him included nobles such as the Earl of Morton, the Chancellor, the King’s advocate and others.[54] |

| l | In this instance “enterprised” is interpreted as “attempted” by Normand and Roberts.[73] |

| m | Maxwell-Stuart refers to her as a witch from Redden but does not supply a name.[67] |

| n | Some academics, for instance Edward J. Cowan, quote 22 June;[68] Normand and Roberts state 2am on 21 June.[80] |

| o | Sir James Sandilands, a favourite of King James,[90] was the brother of the Laird of Pumperston’s fiancée, Mary Sandilands, by marriage as the pair had wed on 15 July 1586 despite Euphame’s efforts to prevent it. Maxwell-Stuart suggests the King may have felt allowing the Sandilands to retain possession of the estate was “a form of poetic justice”.[91][92] |

| p | The Merse is an archaic term used to describe Berwickshire particularly the area encompassing about 20 miles (32 km) west of Kelso.[94] |

| q | The panel was made up of two earls, seven lords and eight barons.[101] |

| r | Some sources quote March[11] whereas others give April[103] for when he left Scotland |

| s | The popularity of detecting witches by pricking led to professionals, such as John KincaidProfessional witch-finder or pricker of witches based in Tranent, East Lothian. , being commonplace in the next two centuries; swimming is only recorded as used once in Scotland, in Aberdeen during 1597, whereas it was common practice in England.[120] |

| t | Quoted by Maxwell-Stuart in The British Witch, referenced to the posthumous publication of Larner’s essays in 1984; the original quote is from the chapter ‘James VI and I and Witchcraft’ appearing on page 79, by Larner within The Reign of James VI and I, published in 1973 |

| u | Julian Goodare describes Larner (1933 – 27 April 1983) as “the most important scholar that Scottish witchcraft had ever had”,[126] an opinion shared by other academics. |

| v | The ODNB entry for the eighth earl gives 4 August[138] |

References

- p. 35

- p. 83

- p. 54

- p. 57

- p. 71

- pp. 180–181

- p. 4

- pp. 22–24

- p. 56

- p. 39

- p. 3

- p. 352

- pp. 3–4

- p. 145

- p. 29

- pp. 30–31

- p. 108

- pp. 966–969

- p. 31

- p. 81

- p. 127

- p. 33

- p. 109

- p. 210

- pp. 209–210

- pp. 139–140

- p. 36

- p. 38

- p. 140

- p. 129

- p. 36

- p. 84

- pp. 109, 142

- p. 142

- pp. 213–214

- pp. 214–215

- p. 144

- pp. 153, 155

- pp. 144–145

- p. 99

- p. 354

- pp. 102–103

- p. 217

- p. 224

- p. 312

- p. 103

- p. 130

- p. 131

- p. 155

- p. 105

- p. 130

- p. 37

- pp. 127, 131

- p. 42

- p. 165

- p. 22

- p. 168

- p. 108

- pp. 108–109

- p. 38

- p. 216

- p. 167

- p. 131

- p. 104

- p. 39

- pp. 158–159

- p. 217

- p. 261

- p. 219

- pp. 203, 219

- p. 160

- p. 112

- p. 132

- p. 113

- p. 23

- p. 220

- p. 40

- pp. 42, 91

- pp. 23, 42

- p. 133

- pp. 202–203

- p. 198

- p. 218

- p. 248

- p. 220

- pp. 161–162

- p. 108

- pp. 131, 132

- pp. 92–92

- p. 133

- p. 137

- p. 46

- pp. 131, 133

- pp. 47, 281

- p. 244

- p. 47

- p. 221

- p. 49

- pp. 137–138

- p. 290

- pp. 291, 297

- pp. 309–324

- p. 123

- p. 40

- p. 302

- p. 306

- p. 42

- pp. 11–12

- p. 329

- p. 332

- p. 85

- pp. 44–45

- p. 45

- pp. 303–304

- p. 41

- p. 2

- p. 116

- p. 418

- p. 301

- p. 240

- p. 65

- p. 71

- p. 68

- p. 174

- p. 304

- p. 241

- pp. 146–147

- pp. 151–152

- p. 35

- pp. 43–44

- p. 34

- p. 36

- p. 44

- pp. 45–46