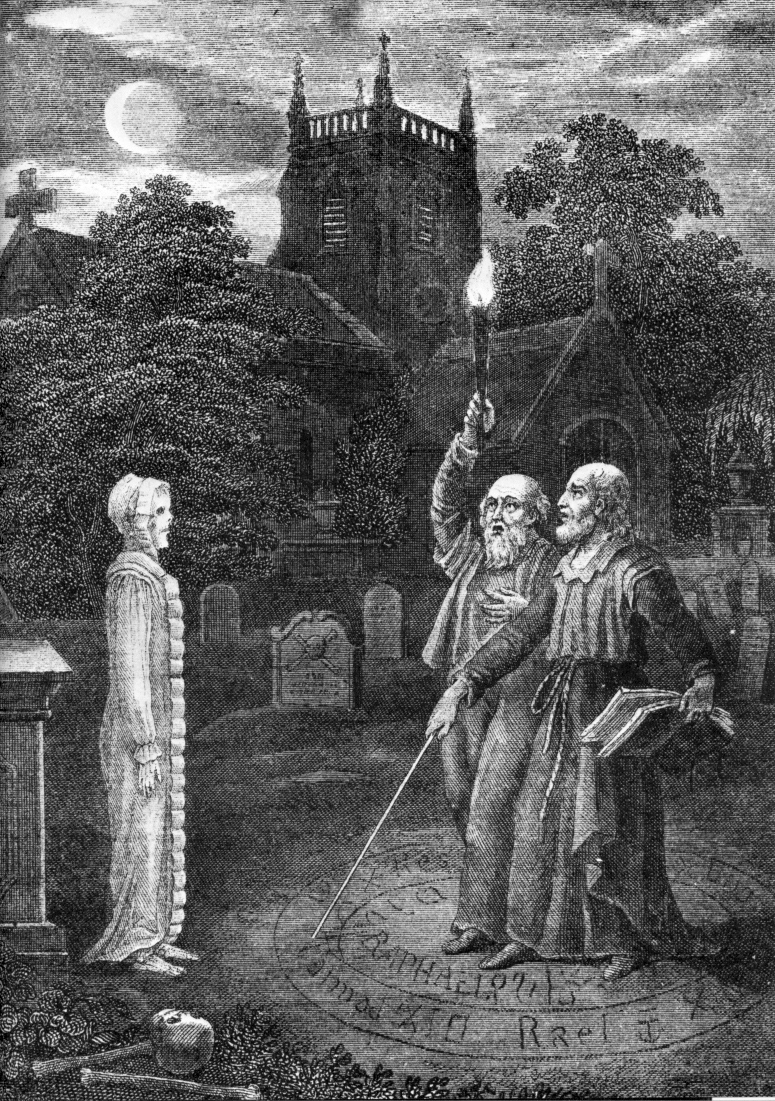

Andrew Spratt, reconstruction, c. 1500

Jean Lyon, Countess of Angus, a member of the Scottish aristocracy, was implicated in the North Berwick witch trialsSeries of Scottish witch trials held between 1590 and 1593 Series of Scottish witch trials held between 1590 and 1593 of 1590. Despite evidence from others that she consulted with witches she was never interrogated or arrested; under the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563Series of Acts passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland making witchcraft a secular offence punishable by death.Series of Acts passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland making witchcraft a secular offence punishable by death., a conviction would have led to the death sentence.

Married three times, Jean’s first two marriages were to powerful members of the Douglas family. Following the death of her second husband, she fell into conflict with the Douglas clan over the inheritance of the earldom of Angus land and title. King James VI influenced her in the choice of her third husband, who was created the first Lord Spynie.

Deeply resented by the ninth Earl of Angus, he grasped the opportunity to seek revenge against her when he learned of her connections to others being persecuted in the cluster of trials associated with North Berwick.

Personal life

Jean’s parents were John Lyon, eighth Lord Glamis and his wife, Elizabeth; the couple married in 1561 and, although Jean’s precise year of birth is unknown, it is likely to be around the mid-1560s.[2][3][a]Carr gives Janet Keith, sister to the fourth Earl Marischal, as the mother of the countess,[3] but according to the ODNB, Janet Keith was her paternal grandmother and Jean’s mother was Elizabeth, daughter of the fifth Lord Saltoun.[2] She had three siblings: one brother and two sisters.[2]

During the years between 1582 to 1585, Jean married her first husband, Robert Douglas the younger of Lochleven, to whom she produced a son, William Douglas, and then she was left a widow when her husband died at sea.[b]Various years are given for these events: Carr gives married in 1583, widowed in 1585 but does not state any year of birth for her son;[3] the ODNB provide 1582 as the year of birth for their son and agree 1585 as the year of death for her husband;[4] The Heraldry of the Douglases gives March 1584 for the time husband is lost at sea.[5] Her second husband was another member of the Douglas family, Archibald Douglas, eighth Earl of Angus, who had been married twice previously.[3][c]He married first Mary Erskine on 13 June 1573; after her death in May 1575 the widower married Margaret Leslie seven months later. He divorced her in 1587 for her infidelity with the third earl of Montrose.[6] They married on 29 July 1587 but the marriage was short-lived as he died on 4/5 August 1588,[d]Peter Maxwell-Stuart and the ODNB give 4 August;[6][7] Carr gives 5 August[8] probably from tuberculosis. Jean was pregnant with their daughter, Margaret, at the time of his death; the child, born on 26 December 1588,[9] later died aged fifteen.[6]

The earldom of Angus was entailed to male heirs and, as the eighth earl had no sons, friction arose over who was entitled to inherit; claimants included the reigning monarch, King James VI and William Douglas of Glenbervie. Jean supported the king’s claim, drawing ire from the Douglas family, particularly from Douglas of Glenbervie. The matter was argued in the courts with the eventual decision being in favour of Douglas, who became the ninth Earl of Angus. Bitterly resenting Jean’s support of his rival claimant, the new earl’s animosity towards her escalated after the king insisted Douglas pay him 40,000 merks.[10][e]The ODNB entry for the ninth earl of Angus gives a figure of 35,000 merks;[11] in The Douglas Book, Fraser suggests the difference between the two figures quoted in older texts is explained by the inclusion of the Chancellor’s fee for his services in the higher figure.[12] A Scots merk was equivalent to 13 shillings 4d.[13]

In May 1590 Jean married her third husband, Alexander Lindsay; at that time Lindsay, who had joined Jean in supporting the King’s attempt to gain the Angus earldom, was a favourite of King James.[14] Lindsay helped fund the flotilla of ships used by the King to collect his new Queen from Denmark in 1589; James promised to give him a peerage as recompense.[15] The King encouraged Jean, who was reticent about the marriage to Lindsay, by pledging in personal correspondence with her that he would ensure Lindsay was raised to a similar rank to her own.[16] As promised Lindsay was elevated to Lord Spynie, which discharged the King’s debt to him of 10,000 gold crowns, and, after their marriage, Lindsay moved into Jean’s home, Aberdour Castle.[1]

The royal couple visited them at Aberdour for a few days at the end of December 1590;[17] the countess and her husband lived in “great splendour” at the castle.[15] By 1591, however, Jean had accumulated many debts being tardy when it came to settling her own liabilities but demanding prompt repayment of any monies due to her.[18]

Jean was left a widow again in June 1607 following the death of Lord Spynie from injuries sustained during an altercation on Edinburgh High Street.[15] The couple’s eldest son, Alexander, born circa 1597, was the heir although still a minor;[19] he had a younger brother and two sisters.[15] Jean’s own exact year of death is uncertain but she lived until the first decade of the 17th-century,[20] likely dying early in 1610.[15]

Witchcraft accusations

Survey of Scottish Witchcraft

Geillis DuncanYoung Scottish maidservant suspected of witchcraft by her employer in November 1590. After being tortured, the initial testimony she gave led to the start of the North Berwick witch trials. , a young maidservant, was interrogated and tortured by her employer, David Seton, in November 1590 because he suspected her of witchcraft.[21] She confessed to being a witch and went on to name several others, including Barbara NapierWoman accused of witchcraft and conspiracy to murder during the North Berwick witch trials., who acted as a lady-in-waiting to the countess.[22] Geillis claimed Barbara had caused the death of Jean’s second husband, the Earl of Angus, by witchcraft.[23] His death, when he was aged thirty-three, was later attributed to witchcraft by his biographer and contemporary;[8] according to the account in Newes from Scotland1591 pamphlet describing the North Berwick witch trials in Scotland, detailing the confessions given by the accused witches before the King., the cause was an illness so mysterious that the doctors were powerless to intervene.[7][24] While employed by the countess, Barbara became acquainted with Francis Stewart, the fifth Earl of Bothwell,[22] a significant figure in the North Berwick witch trialsSeries of Scottish witch trials held between 1590 and 1593 Series of Scottish witch trials held between 1590 and 1593 .[25][f]The Earl of Bothwell’s wife was the eighth Earl of Angus’s sister.[26] She operated as an intermediary between the countess and Agnes SampsonScottish midwife, cunning woman and healer; central figure in the North Berwick witch trials. – an established midwife, cunning woman and healer who had plied her trade since at least 1585 – when the countess encountered marital problems[27] and was also consulted to seek a cure for Jean’s morning sickness.[28] Barbara again approached Agnes when her own relationship with the countess started to breakdown; Agnes applied a charmVerbal charm to be spoken or chanted, sometimes a single magic word such as Abracadabra or the Renervate encountered in the fictional Harry Potter series of books. to a ring that would entice the countess to look favourably on Barbara.[29] The countess and her lady-in-waiting eventually had a disagreement that led to Barbara’s dismissal, which resulted in further arguments between the pair concerning Barbara’s pension.[22]

The countess was connected to several of the other accused witches, including Euphame MacCalzeanWealthy Scottish heiress and member of the gentry convicted of witchcraft. A key figure in the North Berwick witchcraft trials of 1590–1591.,[3] and was mentioned in the depositions given by Agnes in January 1591 and again in Janet Stratton’s examination later that month.[29] Her name continued to appear, including in the list of accusations levelled at Barbara during her trial in May; despite the evidence that she consulted witches, Jean was never interrogated or arrested.[30] The academic Victoria Carr suggests that James “entertained the idea of Jean’s guilt for a few months.”[31] After 7 June, however, no further connections to Jean are made until the earl’s trial in 1593;[32] Bothwell declared that the countess twice asked him to arrange for Ritchie GrahamSorcerer, necromancer and wizard. Executed on the last day of February 1592 as part of the North Berwick witch trials, he was an associate of Francis Stewart, fifth Earl of Bothwell. , a well-known necromancer

Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive. of his acquaintance, to visit and help her husband while he was ill prior to his death.[26]

Modern interpretations

Questions have been raised by modern day academics as to why and how the countess escaped prosecution. Other members of the elite who were of a similar social standing, such as Euphame and Barbara, were tried and convicted so Jean’s position in society was unlikely to be what prevented any action against her.[30] Under the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563Series of Acts passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland making witchcraft a secular offence punishable by death.Series of Acts passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland making witchcraft a secular offence punishable by death., the act used by the courts to try those involved in the North Berwick cluster of trials, a conviction for consulting with witches, would have led to the death sentence.[33]

Historian Louise Yeoman has suggested a pattern of how many of the wealthy women accused of witchcraft may have a basis in feuds over money or property with relatives or other interested parties.[34] Yeoman demonstrated connections between Euphame and David Seton, highlighting the family disputes going on behind those who were accused during this series of trials.[30] Prior to the early confessions of Geillis Duncan, there had been no suggestion that the illness then death of the eighth Earl of Angus was attributed to witchcraft.[35] Academics Julian Goodare and Carr both conclude political manoeuvring on the part of the ninth Earl of Angus led to Jean being named. The disappearance of her name from the proceedings coincides with the sudden death of the Earl on 1 July 1591.[36][37]

Notes

| a | Carr gives Janet Keith, sister to the fourth Earl Marischal, as the mother of the countess,[3] but according to the ODNB, Janet Keith was her paternal grandmother and Jean’s mother was Elizabeth, daughter of the fifth Lord Saltoun.[2] |

|---|---|

| b | Various years are given for these events: Carr gives married in 1583, widowed in 1585 but does not state any year of birth for her son;[3] the ODNB provide 1582 as the year of birth for their son and agree 1585 as the year of death for her husband;[4] The Heraldry of the Douglases gives March 1584 for the time husband is lost at sea.[5] |

| c | He married first Mary Erskine on 13 June 1573; after her death in May 1575 the widower married Margaret Leslie seven months later. He divorced her in 1587 for her infidelity with the third earl of Montrose.[6] |

| d | Peter Maxwell-Stuart and the ODNB give 4 August;[6][7] Carr gives 5 August[8] |

| e | The ODNB entry for the ninth earl of Angus gives a figure of 35,000 merks;[11] in The Douglas Book, Fraser suggests the difference between the two figures quoted in older texts is explained by the inclusion of the Chancellor’s fee for his services in the higher figure.[12] A Scots merk was equivalent to 13 shillings 4d.[13] |

| f | The Earl of Bothwell’s wife was the eighth Earl of Angus’s sister.[26] |