Wikimedia Commons

Grub Street is a pejorative term that became synonymous with hack writers and low-quality journalism. Until the early 19th century it was a street close to London’s impoverished Moorfields district, running from Fore Street east of St Giles-without-Cripplegate north to Chiswell Street. Famous for its concentration of impoverished “hack writers”, aspiring poets, and low-end publishers and booksellers, Grub Street existed on the margins of London’s journalistic and literary scene, set amidst the impoverished neighbourhood’s low-rent dosshouses, brothels and coffeehouses.

According to Samuel Johnson18th-century English writer, critic, editor and lexicographer whose Dictionary of the English Language had far-reaching effects on the development of Modern English.‘s Dictionary, the term was “originally the name of a street … much inhabited by writers of small histories, dictionaries, and temporary poems, whence any mean production is called grubstreet”; Johnson himself had lived and worked on Grub Street early in his career. The contemporary image of Grub Street was popularised by Alexander Pope in his Dunciad. The street was later renamed Milton Street, which was partly swallowed up by the Barbican Estate development, but still survives in part.

Grub Street appears to have taken its name from a refuse ditch that ran alongside (grub); variations on the name include Grobstrat (1217–1243), Grobbestrate (1277–1278), Grubbestrate (1281), Grubbestrete (1298), Grubbelane (1336), Grubstrete, and Crobbestrate.[1][2][3] Grub is also a derogatory noun applied to “a person of mean abilities … a literary hack … a person of slovenly attire and unpleasant manners.”[4]

Early history

Grub Street was in Cripplegate ward, in the parish of St Giles-without-Cripplegate (Cripplegate ward was bisected by the city walls, and therefore was both “within” and “without”).[5][6] Much of the area was originally extensive marshlands from the Fleet Ditch, to Bishopsgate, contiguous with Moorfields to the east.[7] The St Alphage Churchwardens’ Accounts of 1267 mention a stream running from the nearby marsh, through Grub Street, and under the city walls into the Walbrook river, which may have provided the local population with drinking water.[8]

One of Grub Street’s early residents was the notable recluse Henry Welby, the owner of the estate of Goxhill in Lincolnshire. In 1592 his half-brother attempted to shoot him with a pistol. Shocked, he took a house on Grub Street and remained there, in near-total seclusion, for the rest of his life. He died in 1636 and was buried at St Giles in Cripplegate.[9]

An early use of the land surrounding Grub Street was for archery. In Records of St. Giles’ Cripplegate (1883), the author describes an order made by Henry VII to convert Finsbury Fields from gardens, to fields for archery practice,[10] but in Elizabethan times archery became unfashionable, and Grub Street is described as largely deserted, “except for low gambling houses and bowling-alleys – or, as we should call them, skittle-grounds.”[11] John Stow also referred to Grubstreete in A Survey of London Volume II (1603) as “It was convenient for bowyers, since it lay near the Archery-butts in Finsbury Fields”; in 1651 the poet Thomas Randoph wrote “Her eyes are Cupid’s Grub-Street: the blind archer, Makes his love-arrows there.”[12] The Little London Directory of 1677 lists six merchants living in “Grubſreet”, and Costermongers also plied their trade – a Mr Horton, who died in September 1773, earned a fortune of £2,000 by hiring out wheelbarrows.[13][14] Land was cheap and occupied mostly by the poor, and the area was renowned for the presence of Ague and the Black Death; in the 1660s the Great Plague of London killed almost eight thousand of the parish’s inhabitants.[7]

The population of St Giles in 1801 has been estimated at about 25,000 people, but by the end of the 19th century this was dropping steadily.[15] In the 18th century Cripplegate was well known as an area haunted by insalubrious folk,[7] and by the mid-19th century crime was rife. Methods of dealing with criminals were severe; thieves and murderers were “left dangling in their chains on Moorfields.”[16] The use of gibbets was common, and four “cages” were maintained by the parish, for use as a Lying-in hospital, housing the poor, and “idle imposters”. One such cage stood amid the poor-quality housing stock of Grub Street;[16][17] destitution was viewed as a crime against society, and was punishable by whipping and having a hole cut in the gristle of the right ear.[18]

Well before the influx of writers in the 18th century, Grub street was therefore in an economically deprived area.[3]

Early literature

The earliest literary reference to Grub Street appears in 1630, by the English poet, John Taylor. “When strait I might descry, The Quintescence of Grubstreet, well distild Through Cripplegate in a contagious Map”.[19] The local population was known for its nonconformist views; its Presbyterian preacher Samuel Annesley had been replaced in 1662 by an Anglican. Famous 16th-century Puritans included John Foxe, who may have written his Book of Martyrs in the area,[16] the historian John Speed, the Protestant printer and poet Robert Crowley. The Protestant John Milton also lived near Grub Street.[20]

Press freedom

In 1403 the City of London Corporation approved the formation of a Guild of stationers, comprised of booksellers, illuminators, and bookbinders.[21] Printing gradually displaced manuscript production, and by the time that the Guild received a royal charter of incorporation on 4 May 1557, becoming the Stationers’ Company, it was in effect a Printers’ Guild with considerable powers of search and seizure. Backed by the state – which supplied the force and authority to guarantee copyright – this monopoly continued until 1641, when inflamed by the treatment of religious dissenters such as John Lilburne and William Prynne, the Long Parliament abolished the Star Chamber (a court which controlled the press) with the Habeas Corpus Act 1640. This led to the de facto cessation of state censorship of the press. Although in 1641 token punishments were handed out to those responsible for unlicenced and hostile pamphlets published around London – including in Grub Street – Puritan and radical pamphlets continued to be distributed by an informal network of street hawkers, and dissenters from within the Stationers’ Company.[20][22][23] Tabloid journalism[a]The Oxford English Dictionary dates the earliest use of the word journalist to 1693 – Humours Town 78 Epistle-Writer, or Jurnalists, Mercurists. became rife; the unstable political climate resulted in the publication from Grub Street of anti-Caroline literature, along with blatant lies and anti-Catholic stories regarding the Irish Rebellion of 1641; stories that were advantageous to the parliamentary leadership. Following the King’s failed attempt to arrest several members of the Commons, Grub Street printer Bernard Alsop became personally involved in the publication of false pamphlets, including a fake letter from the Queen that resulted in John Bond being pilloried. Alsop and colleague Thomas Fawcett were sent to Fleet Prison for several months.[24]

Throughout the English Civil War therefore, publishers and writers remained answerable to the law. State control of the press was tightened in the Licensing Order of 1643, but although the new regime was arguably as restrictive as the monopoly that the Stationers’ Company once enjoyed, parliament was unable to control the number of renegade presses that flourished during the Interregnum.[25] The freedoms ensured by the Bill of Rights 1689 led indirectly to the refusal in 1695 of the Parliament of England to renew the Licensing of the Press Act 1662, a law which required all printing presses to be licensed by parliament. This lapse led to a freer press, and a rise in the volume of printed matter. Jonathan Swift wrote to a friend in New York, “I could send you a great deal of news from the Republica Grubstreetaria, which was never in greater altitude.”[26]

Hacks

Wikimedia Commons

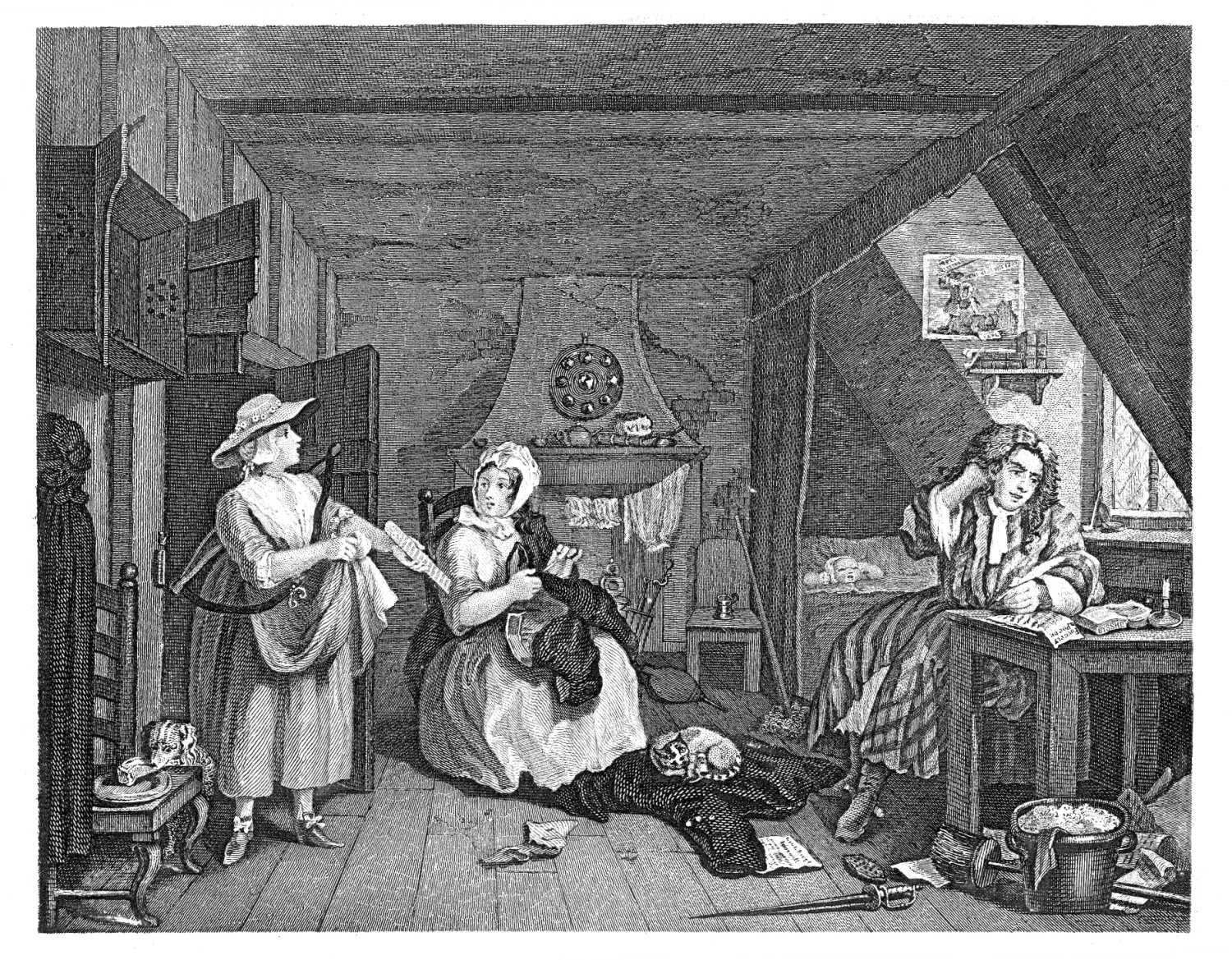

Publishing houses proliferated in Grub Street, and this, combined with the number of local garrets, meant that the area was an ideal home for hack writers. In The Preface, when describing the harsh conditions a writer suffered, Tom Brown’s self-parody referred to being “Block’d up in a Garret”.[28] Such contemporary views of the writer, in his inexpensive Ivory Tower high above the noise of the city, were immortalised by William Hogarth in his 1736 illustration The Distrest Poet. The street name became a synonym for a hack writer; in a literary context, “hack” is derived from Hackney – a person employed to do menial or servile work, a drudge.[29] The satirical writer Ned Ward’s late 17th-century description reinforces a common view of Grub Street authors, as little more than prostitutes:[30]

— Ned Ward (1698)

One such author was Samuel Boyse. Contemporary accounts picture him as a dishonest and disreputable rogue, paid for each individual line of prose as a Jack of all trades, master of none. He apparently lived in squalor, often drunk, and on one occasion after pawning his shirt, he fashioned a replacement out of paper.[31] To be a called a “Grub Street author” was therefore often viewed as an insult,[32] but Grub Street hack James Ralph defended the trade of the journalist, contrasting it with the supposed hypocrisy of more esteemed professions:[33]

— James Ralph (1758)

Periodicals

In response to an increasing demand for reading matter, Grub Street became a popular source of periodical literature. One publication to take advantage of the reduction of state control was A Perfect Diurnall (despite its title, a weekly publication). However it quickly found its name copied by unscrupulous Grub Street publishers, so obviously that the newspaper was forced to issue a warning to its readers.[34] Toward the end of the 17th century authors including as John Dunton worked on a range of periodicals, including Pegasus (1696), and The Night Walker: or, Evening Rambles in search after lewd Women (1696–1697). Dunton pioneered the advice column in Athenian Mercury (1690–1697). Ned Ward published The London Spy (1698–1700) in monthly instalments, for more than a year and a half. It was conceived as a guide to the sights of the city, but as a periodical also contained details on taverns, coffee-houses, tobacco shops, cheap lodging houses and brothels.[35]

Other publications included the Whig Observator (1702–1712), and the Tory Rehearsal (1704–1709), both superseded by Daniel Defoe’s Weekly Review (1704–1713), and Jonathan Swift’s Examiner (1710–1714).[36] English newspapers were often politically sponsored, and several such publications were based in Grub Street; between 1731 and 1741 Robert Walpole’s ministry was reported to have spent about £50,077 (equivalent to about £7 million as at 2018[37]) of treasury funds on bribes to such newspapers. Allegiances changed often, with some authors changing their political stance on receipt of bribes from secret service funds.[38] Such changes helped maintain the level of disdain with which the establishment viewed journalists and their trade, an attitude often reinforced by the abuse publications would print about their rivals. Titles such as Common Sense, Daily Post, and the Jacobite’s Journal (1747–1748) were often guilty of this practice, and in May 1756 an anonymous author described journalists as “dastardly mongrel insects, scribbling incendiaries, starveling savages, human shaped tygers, senseless yelping curs”.[39] In describing his profession, Samuel Johnson, a Grub Street man himself,[40] said “A news-writer is a man without virtue who writes lies at home for his own profit. To these compositions is required neither genius nor knowledge, neither industry nor sprightliness, but contempt of shame and indifference to truth are absolutely necessary.”[41]

— Grub Street JournalWeekly satirical newspaper published from 1730 until 1737.Weekly satirical newspaper published from 1730 until 1737. (1731)

Taxation

In 1711 Queen Anne gave royal assent to the 1712 Stamp Act, which imposed new taxes on newspapers. The Queen addressed the House of Commons: “Her majesty finds it necessary to observe, how great license is taken in publishing false and scandalous libels, such as are a reproach to any Government. This evil seems to be grown too strong for the laws now in force. It is therefore recommended to you to find a remedy equal to the mischief.”[43] The passage of the Act was partly an attempt to silence Whig pamphleteers and dissenters, who had been critical of the then Tory government. Every copy of a news-carrying publication printed on a half-sheet of paper became liable to a duty of a halfpenny, and if printed on a full sheet, a penny. A duty of a shilling was placed on advertisements. Pamphlets were charged a flate rate of two shillings per sheet for each edition, and were obliged to include the name and address of the printer.[44] The introduction of the Act caused protests from publishers and authors alike, including Daniel Defoe, and Jonathan Swift, who in support of the Whig press wrote:

— Jonathan Swift (1712)[43]

Although the Act had the side-effect of closing down several newspapers, publishers used a weakness in the legislation which meant that newspapers of six pages (a half-sheet and a whole sheet) were only charged at the flat pamphlet rate of two shillings per sheet (regardless of the number of copies printed). Many publications thus expanded to six pages, filled the extra space with extraneous matter, and raised their prices to absorb the tax. Newspapers also used the extra space to introduce serials, hoping to hook readers into buying the next instalment. The periodical nature of the newspaper allowed writers to develop their arguments over successive weeks, and it began to overtake the pamphlet as the primary medium for political news and comment.[46]

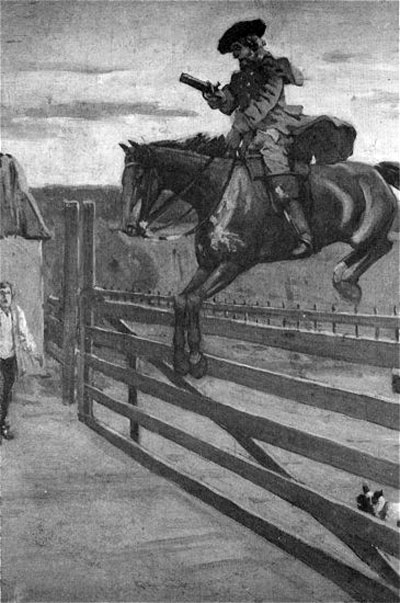

By the 1720s “Grub Street” had grown from a street name into a term for all manner of low-level publishing.[47] The popularity of Nathaniel Mist’s Weekly Journal gave rise to a plethora of new publications, including the Universal Spectator (1728), the Anglican Weekly Miscellany (1732), the Old Whig (1735), Common Sense (1737), and the Westminster Journal.[48] Such publications could be strident in their criticism of government ministers – Common Sense in 1737 compared Walpole to the infamous outlaw Dick Turpin

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess.:

— Common Sense (1737)

In response, a 1737 edition of the Craftsman proposed a tax on urine, and ten years later the Westminster Journal, in a critique of proposed new taxes on food, servants, and malt, proposed a tax on human excrement.[50]

Not all publications were based entirely on politics however. The Grub Street Journal was better known in literary circles for its combative nature, and has been compared to the modern-day Private Eye. Despite its name, it was printed on nearby Warwick Lane. It began in 1730 as a literary journal and became known for its bellicose writings on individual authors. It is considered by some to have been a vehicle for Alexander Pope’s attacks on his enemies in Grub Street, but although he contributed to early issues the full extent of his involvement is unknown. Once his interest in the publication waned The Journal began to generalise, satirising medicine, theology, theatre, justice, and other social issues. It often contained contradictory accounts of events reported by the previous week’s newspapers, its writers inserting sarcastic remarks on the inaccuracies printed by their rivals.[51] It ran until 1737 when it became the Literary Courier of Grub-street, which lingered for a further six months before vanishing altogether.[52]

Newspapers and their authors were not yet completely free from state control. In 1763 John Wilkes was charged with seditious libel for his attacks on a speech by George III, in issue 45 of The North Briton. The King felt personally insulted and general warrants were issued for the arrest of Wilkes and the newspaper’s publishers. Wilkes was arrested, convicted of libel, fined, and imprisoned. During their search for Wilkes, the King’s messengers had visited the home of a Grub Street printer named John Entick, who had printed several copies of The North Briton, but not number 45. The messengers spent four hours searching his home, and eventually carried away more than two hundred unrelated charts and pamphlets. Wilkes had filed for damages against the Under Secretary of State Robert Woods and won his case, and two years later Entick pursued the chief messenger Nicholas Carrington in similar fashion – and was awarded £2,000 in compensation. Carrington appealed, but was ultimately unsuccessful; Chief Justice Camden upheld the verdict with a landmark judgement that established the limits of executive power in English law, that an officer of the state could only act lawfully in a manner prescribed by statute or common law.[53][54] The judgement also formed part of the background to the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[55]

Infighting

In 1716 the bookseller and publisher Edmund Curll acquired a manuscript that belonged to Alexander Pope. Curll advertised the work as part of a forthcoming volume of poetry, and was soon contacted by Pope who warned him not to publish the poems. Curll ignored him and published Pope’s work under the title Court Poems. A meeting between the two was arranged, at which Pope poisoned Curll with an emetic. Several days later Pope also published two pamphlets describing the meeting, and proclaimed Curll’s death. He hoped that the combination of the poisoning and the wit of his writing would change the public view of Curll from a victim, to a deserving villain. Meanwhile, Curll responded by publishing material critical of Pope and his religion. The incident, meant to secure Pope’s status as an elevated figure among his peers, created a lifelong and bitter rivalry between the two men, but may have been beneficial to both; Pope as the man of letters under constant attack from the hacks of Grub Street, and Curll using the incident to increase the profits from his business.[56]

Pope later immortalised Grub Street in his 1728 poem The Dunciad, a satire of “the Grub-street Race” of commercial writers.[57] Such infighting was not unusual, but a particularly notable episode occurred from 1752–1753, when Henry Fielding started a “paper war” against hack writers on Grub Street. Fielding had worked in Grub Street during the late 1730s. His career as a dramatist was curtailed by the Theatrical Licensing Act (provoked by Fielding’s anti-Walpole satires such as Tom Thumb and Covent Garden Tragedy) and he turned to law, supporting his income with normal Grub Street work. He also launched The Champion, and over the following years edited several newspapers, including from 1752–1754 The Covent-Garden Journal.[58]

The avarice of the Grub Street press was often demonstrated by the manner in which they treated notable, or notorious public figures. John Church, an independent minister born in 1780, raised the ire of the local hacks when he admitted he had acted ‘”imprudently” following allegations he had sodomised young men in his congregation.[59] Satire was a popular pastime – the Mary ToftEnglish woman from Godalming, Surrey, who in 1726 became the subject of considerable controversy when she tricked doctors into believing that she had given birth to rabbits. affair of 1726, concerning a woman who fooled some of the medical establishment into believing she had given birth to rabbits – produced a notable dirge of diaries, letters, satiric poems, ballads, false confessions, cartoons, and pamphlets.[60]

Later history and legacy

Grub Street was renamed Milton Street in 1830, apparently in memory of a tradesman who owned the building lease of the street.[61] By the middle of the 19th century it had lost some of its negative connotations; authors were by that time viewed in the same light as traditionally more esteemed professions,[32] although “Grub Street” remained a metaphor for the commercial production of printed matter, regardless of whether such matter actually originated from Grub Street itself.

As Grub Street became a metaphor for the commercial production of printed matter, the term gradually spread to early 18th-century America. Early publications such as handwritten ditties and squibs were circulated among the gentry and taverns and coffee-houses. As in England, many were directed at politicians of the day.[62]

Notes

| a | The Oxford English Dictionary dates the earliest use of the word journalist to 1693 – Humours Town 78 Epistle-Writer, or Jurnalists, Mercurists. |

|---|

References

- p. 3

- p. 24

- p. 15

- p. 35

- pp. 23–24

- p. 168

- p. 109

- p. 85

- pp. 356–374

- pp. 33, 85, 109, 120, 126, 127

- p. 174

- p. 25

- p. 26

- p. 87

- pp. 87–88

- p. 116

- p. 85

- pp. 31–34

- pp. 38–39

- pp. 40–42

- pp. 104–105

- p. 5

- pp. 15–16

- p. 3

- p. 6

- p. 385

- p. 2

- p. 17

- p. 30

- pp. 45–46

- pp. 58–69

- pp. 7–9

- p. 60

- p. 9

- pp. 58–60

- p. 76

- pp. 48–49

- p. 384

- pp. 49–50

- p. 3

- p. 60

- p. 61

- p. 62

- pp. 62–63

- pp. 3–4

- pp. 120–123

- pp. 3–4

- pp. 1–2

- p. 241

- p. 120