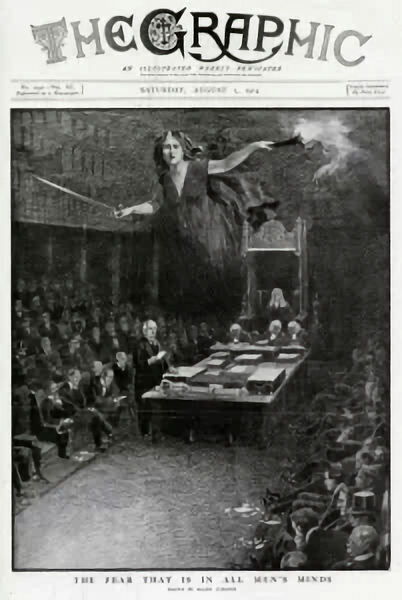

Montezuma’s Daughter, first published in 1893, is a novel written by the Victorian adventure writer H. Rider Haggard.[1] First serialised in The Graphic British weekly illustrated newspaper published from 1869 to 1932. between 1 July and 11 November 1893,[2] it is narrated in the first person by Thomas Wingfield of Ditchingham, an Englishman who is purportedly writing an account of his adventures when caught up in Hernán Cortés’s invasion of the Aztec capital Tenoctitlan, at the express command of Queen Elizabeth I. He is writing as an old man, very near the end of his life.

British weekly illustrated newspaper published from 1869 to 1932. between 1 July and 11 November 1893,[2] it is narrated in the first person by Thomas Wingfield of Ditchingham, an Englishman who is purportedly writing an account of his adventures when caught up in Hernán Cortés’s invasion of the Aztec capital Tenoctitlan, at the express command of Queen Elizabeth I. He is writing as an old man, very near the end of his life.

The plot is constructed from three interlocking storylines: Cortés’s victory over the Aztec Empire in what is modern-day Mexico in 1519–1521; Wingfield’s participation in the struggle, fighting with the Aztecs against the Spanish; and Wingfield’s personal relationships with Lily Bozard, his English fiancée, Don Juan de Garcia, his mother’s murderer, on whom he is seeking revenge, and his Aztec wife Princess Otomie.

Plot summary

Wingfield’s adventures begin with the revenge killing of his Spanish mother. Many years earlier she had fled an arranged marriage to the Spaniard Juan de Garcia to marry Wingfield’s father, and de Garcia has not forgiven her. Leaving behind his fiancée Lily, Wingfield pursues his mother’s murderer back to Spain, where he witnesses the Inquisition’s execution of a young pregnant nun on de Garcia’s evidence, even though he was the one responsible for her condition. Wingfield takes passage on a ship from Spain to Hispaniola, which is destroyed in a storm. He takes to one of the small boats and is picked up by a nearby slave ship, on board which is de Garcia, who despite claiming that Wingfield is an English spy who deserves to die, is persuaded to allow the other sailors to sell him into slavery. Wingfield escapes by throwing himself overboard and succeeds in reaching the shore of what he learns is Mexico. Captured by natives, he is taken to the city of Tobasco, to be sacrificed to the gods.

Wingfield is saved at the last minute, as his pale skin persuades his captors that he may be a child of Quetzal, the god to whom he is to be sacrificed. Learning of the new arrival, Montezuma, king of the Aztecs, sends his nephew, Guatemoc, to escort Wingfield to his capital, Tenoctitlan. There he is worshipped as the embodiment of the Aztec god, Tezcat, and becomes a ceremonial figurehead for a year, before being married to four sacrificial virgins including Otomie, Montezuma’s daughter.[a]Otomie is a fictitious character. Montezuma had many wives, and a correspondingly large family. According to a Spanish chronicler, by the time he was taken captive, Montezuma had fathered 100 children, the names of most of whom are lost to us.[3] Lying with Otomie on the sacrificial altar awaiting their fate, the pair are saved by the arrival of the Spanish, who have been fighting to take the city for some time. To their mutual astonishment, Wingfield’s rescuer is de Garcia, who has joined Cortés’s invasion force. Wingfield and Otomie succeed in making their escape from the Spaniards, and Wingfield joins forces with the Aztecs in their struggle against the conqistadors.

The fight goes badly for the Aztecs, and Wingfield is seized by the Spaniards and tortured to reveal the whereabouts of Montezuma’s treasure. He and Otomie are helped to escape, and they flee to the City of Pines, where they live peacefully for many years until the Spanish decide to besiege the city. Under Wingfield’s leadership the population resists, but in their final madness many of the women begin to sacrifice humans. Wingfield and a few others manage to rescue five Spaniards who are chained up waiting their turn on the sacrifical altar, prompting their commander to offer pardons to everyone not involved in the sacrifices if the defenders surrender, which they are forced to do; Wingfield, Otomie and their son, are thus released.

Once again de Garcia has been in the attacking Spanish force, but he slips away before Wingfield can confront him, after killing Wingfield’s son. Wingfield sees de Garcia making his escape towards the slopes of Xaca, an active volcano, and catches him at its summit. The pair fight, and de Garcia falls to his death into the fiery crater. “Thus then did I accomplish the vengeance that I had sworn to my father I would wreak upon de Garcia”.

Grieving at the death of her son and the knowledge that Wingfield’s true love is Lily, his fiancée back in England, Otomie commits suicide. Wingfield takes passage on a ship to Cadiz and thence to London, taking with him the “collar of great emeralds” given to him by Guatemoc. He returns to Ditchingham, where he is reunited with Lily, who has waited faithfully for his return; they kiss again for the first time in eighteen years, a year to the day since Otomie died.

Autographical background

While in Mexico in 1891 researching for the book, Haggard received news that his only son, Jock, had died, which dealt him a lasting blow and badly affected his health.[4]

Haggard wrote Montezuma’s Daughter in Ditchingham House, where Wingfield writes his memoirs in the book. Haggard’s wife had inherited the estate in 1880, and in 1891 the family made it their permanent residence after Jock’s death. In the words of the literary historian Richard Pearson, the house represents “a symbolic link between Montezuma’s Daughter and Haggard’s personal life”.[2]

Critical reception

A reviewer writing in the New York Times of 26 November 1893 complained that “oceans of gore are distasteful and Mr. Haggard revels in that kind of inundation”.[2] Haggard himself recognised that Montezuma’s Daughter was the last of his best work “for the rest was repetition so far as fiction was concerned”.[5]

Notes

| a | Otomie is a fictitious character. Montezuma had many wives, and a correspondingly large family. According to a Spanish chronicler, by the time he was taken captive, Montezuma had fathered 100 children, the names of most of whom are lost to us.[3] |

|---|

References

Works cited

External links

- Full text of Montezuma’s Daughter at Project Gutenberg