Trafford Town HallOfficially opened as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford's charter on 16 September 1933. Officially opened as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford's charter on 16 September 1933. Officially opened as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford's charter on 16 September 1933. , Stretford

Wikimedia Commons

Stretford is one of the four major urban areas in the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford in Greater Manchester, the other three being Altrincham, Sale and Urmston.[1] It occupies flat ground between the River Mersey to the south and the Manchester Ship Canal in the north, 3.8 miles (6.1 km) south of Manchester city centre and 3 miles (4.8 km), south of the City of Salford, bisected by the Bridgewater Canal.

The architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner has remarked that “Stretford is part of Manchester functionally and visually and the boundary … is nowhere noticeable”.[2] Within the boundaries of the historic county of Lancashire, in the 19th century Stretford was an agricultural village known locally as Porkhampton, owing to the large number of pigs produced for the Manchester market.[a]A local dish known as Stretford Goose consisted of pork stuffed with sage and onions.[3] It was also an extensive market-gardening area, producing more than 500 tons of vegetables each week for sale in Manchester by 1845. The arrival of the Manchester Ship Canal

36-mile-long (58 km) inland waterway in the North West of England linking Manchester to the Irish Sea. in 1894, and the subsequent development of the Trafford ParkFirst planned industrial estate in the world, and still the largest in Europe.First planned industrial estate in the world, and still the largest in Europe. industrial estate, accelerated the industrialisation that began in the late 19th century.

Stretford has been the home of Manchester United Football Club since 1910,[4] and of Lancashire County Cricket Club since the club’s formation in 1864.[5]

Geography

Stretford occupies an area of 4.1 square miles (10.6 km2), just north of the River Mersey, at 53°26′48″N 2°18′31″W (53.4466, −2.3086). The area is generally flat, sloping slightly southwards towards the river valley,[6] and is approximately 150 feet (46 m) above sea level at its highest point.[7] The most southerly part of Stretford lies within the flood plain of the River Mersey, and so has historically been prone to flooding. A great deal of flood mitigation work has been carried out in the Mersey Valley since the 1970s, with the stretch of the Mersey through Stretford canalised to speed up the passage of floodwater.[8] Emergency floodbasins have also been constructed, Sale Water ParkParkland including a large artificial lake created by gravel extraction, a wildlife reserve, and part of the surrounding area's flood defences. being a prominent local example, lying immediately to the south of Stretford.[9]

Wikimedia Commons

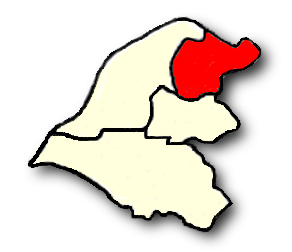

Stretford comprises the local areas of Old Trafford, Firswood, Gorse Hill and Trafford Park, and represents the northeastern tip of Trafford. Its built environment developed in two sections along the A56 road, the principal road through the town, corresponding to the two original manors. The area in the south, near to the border with Sale, grew around the church of St Matthew, while the northern part of Stretford was centred on Old Trafford, the two separated by undeveloped countryside; the sections merged during the 19th century.[10]

History

The origin of the name Stretford is “street” (Old English strǣt) on a ford across the River Mersey.[11] The A56 Chester Road, follows the line of the old Roman road from Deva Victrix (Chester) to Mamucium (Manchester), crossing the Mersey into Stretford at Crossford Bridge, built at the location of the ancient ford.[6] The earliest evidence of human occupation comes from Neolithic stone axes found in the area, dating from about 2000 BCE. Stretford was part of the land occupied by the Celtic Brigantes tribe before and during the Roman occupation, and lay on their border with the Cornovii on the southern side of the Mersey.[12]

By 1212 there were two manors in the area now called Stretford. The land in the south, close to the River Mersey, was held by Hamon de Mascy, while the land in the north, closer to the River Irwell, was held by Henry de Trafford.[13] In about 1250 a later Hamon de Mascy gave the Stretford manor to his daughter, Margery. She in turn, in about 1260, granted Stretford to Richard de Trafford at a rent of one penny. The de Mascy family shortly afterwards released all rights to their lands in Stretford to Henry de Trafford, the Trafford family thus acquiring the whole of Stretford, since when the two manors descended together.[6]

The de Trafford family leased out large parts of the land, much of it to tenants who farmed at subsistence levels. Although there is known to have been a papermill operating in 1765, the area remained largely rural until the early 20th-century development of Trafford ParkFirst planned industrial estate in the world, and still the largest in Europe.First planned industrial estate in the world, and still the largest in Europe. in the Old Trafford district in the north of the town.[14] Until then Stretford “remained in the background of daily life in England”, except for a brief cameo role during the Jacobite rising of 1745, when Crossford Bridge was destroyed to prevent a crossing by Bonnie Prince Charlie’s army during its abortive advance on London; the bridge was quickly rebuilt.[15]

Until the 1820s one of Stretford’s main cottage industries was the hand-weaving of cotton. There were reported at one time to have been 302 handlooms operating in Stretford, providing employment for 780 workers, but by 1826 only four were still in use, as the mechanised cotton mills of nearby Manchester replaced handlooms.[16] As Manchester continued to grow, it offered a good and easily accessible market for Stretford’s agricultural products, in particular rhubarb, once known locally as Stretford beef.[17] By 1836 market gardening had become so extensive around Stretford that one writer described it as the “garden of Lancashire”;[18] in 1845 more than 500 tons of vegetables were being produced for the Manchester market each week.[19] Stretford also became well known for its pig market and the production of black puddings, leading to the village being given the nickname of Porkhampton. A local dish, known as Stretford goose, was made from pork stuffed with sage and onions. During the 1830s, between 800 and 1000 pigs a week were being slaughtered for the Manchester market.[20]

Situated on the border with Manchester, Stretford became a fashionable place to live in the mid-19th century.[21] Large recreation areas were established, such as the Royal Botanical Gardens, opened in 1831. The gardens were sited in Old Trafford on the advice of scientist John Dalton, because the prevailing southwesterly wind kept the area clear of the city’s airborne pollution.[22] In 1857 the gardens hosted the Art Treasures ExhibitionExhibition of fine art art held in Manchester in 1857, the largest art exhibition ever in the UK., the largest art exhibition ever held in the United Kingdom.[23] A purpose-built iron and glass building was constructed at a cost of £38,000 to house the 16,000 exhibits.[24] The gardens were also chosen as a site for the Royal Jubilee Exhibition of 1887Exhibition in Old Trafford, Manchester, England in 1887 to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria's accession. , celebrating Queen Victoria’s 50-year reign. The exhibition ran for more than six months and was attended by more than 4.75 million visitors.[25] The gardens were converted into an entertainment resort in 1907, and hosted the first speedway meeting in Greater Manchester on 16 June 1928.[26] There was also greyhound racing from 1930, and an athletics track. The complex was demolished in the late 1980s, and all that remains is the entrance gates, close to what is now the White City Retail ParkFormer botanical gardens that hosted the largest art exhibition ever held in the UK, now a retail park.. The gates were designated a Grade II listed structure in 1987.[27]

Industrialisation

The arrival of the Manchester Ship Canal in 1894, and the subsequent development of the Trafford Park industrial estate in the north of the town – the first planned industrial estate in the world[28] – had a substantial effect on Stretford’s growth. The population in 1891 was 28,59791, but by 1901 it had increased by 70% to 40,686 as people were drawn to the town by the promise of work in the new industries at Trafford Park.[29][30]

During the Second World War Trafford Park was largely turned over to the production of matériel, including the Avro Manchester heavy bomber and the Rolls-Royce Merlin engines used to power both the Spitfire and the Lancaster.[31][b]The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine was made by Ford, under licence. The factory produced 34,000 engines, and employed 17,316 people.[31] That resulted in Stretford being the target for heavy bombing, particularly during the Manchester BlitzHeavy bombing of the city of Manchester and its surrounding areas in North West England during the Second World War by the Nazi German Luftwaffe. of 1940. On the nights of 22/23 and 23/24 December 1940 alone, 124 incendiaries and 120 high-explosive bombs fell on the town, killing 73 people and injuring many more. Among the buildings damaged or destroyed during the war were Manchester United’s Old Trafford football ground, All Saints’ Church, St Hilda’s Church, and Stretford Girls’ High School.[32] Smoke generators were set up in the north of the town close to Trafford Park in an effort to hide it from enemy aircraft,[33] and 11,900 children were evacuated to safer areas in Lancashire, Cheshire, Derbyshire, and Staffordshire, along with their teachers and supervisors.[34]

Transport history

Stretford’s growth was fuelled by the transport revolutions of the 18th and especially the 19th century: the Bridgewater Canal reached Stretford in 1761, and the railway in 1849. The completion of the Manchester South Junction and Altrincham Railway (MSJAR) in 1849, passing through Stretford, led to the population of the town nearly doubling in a decade, from 4,998 in 1851 to 8,757 by 1861.[35]

Because Stretford is situated on the main A56 road between Chester and Manchester many travellers passed through the village, and as this traffic increased, more inns were built to provide travellers with stopping places. One of the earliest forms of public transport through Stretford was the stagecoach. The main setting-down and picking-up points were the Angel Inn and the Trafford Arms, both now demolished.[36] Horse-drawn omnibuses replaced the stagecoach service through Stretford in 1845.[37] The Manchester Carriage CompanyCompany established on 1 March 1865 to provide horse-drawn bus services throughout Manchester and Salford, in England. ‘s tramway from Manchester to Stretford was built in 1879, terminating at the Old Cock Hotel on the A56 road, next to which a small depot was built to house the cars and horses.[38] A 1900 timetable shows that trams left for Manchester every ten minutes between 8:00 am and 10:15 pm.[39] The horse-drawn trams were replaced with electric trams in 1902,[40] and after the Second World War the trams were replaced by buses.[41]

The MSJAR railway line through Stretford was electrified in 1931 and converted to light rail operation in 1992, when it became part of the Manchester Metrolink tram network.[42]

Governance

Civic history

Stretford was part of the ancient parishAncient or ancient ecclesiastical parishes encompassed groups of villages and hamlets and their adjacent lands, over which a clergyman had jurisdiction. of Manchester, within the historic county boundaries of Lancashire.[43] Following the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, a national scheme for dealing with the relief of the poor, Stretford joined the Chorlton Poor Law Union in 1837, one of three such unions in Manchester,[44] before transferring to the Barton-upon-Irwell Poor Law Union in 1849.[45] In 1867 Stretford Local Board of Health was established, assuming responsibility for the local government of the area in 1868.[46] The board’s responsibilities included sanitation and the maintenance of the highways, and it had the authority to levy rates to pay for those services. The local board continued in that role until it was superseded by the creation of Stretford Urban District Council in 1894,[47] as a result of the Local Government Act 1894.[48]

Stretford Urban District became the Municipal Borough of StretfordCreated in 1894 and granted a charter of incorporation in 1933, becoming a municipal borough. Abolished in 1974, the area it controlled is now part of the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford in Greater Manchester. in 1933,[49] giving it borough status in the United Kingdom, and was granted its arms on 20 February 1933.[50] In 1974, as a result of the Local Government Act 1972, the Municipal Borough of Stretford was abolished and Stretford has, since 1 April 1974, formed part of the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford, in Greater Manchester. Trafford Town HallOfficially opened as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford's charter on 16 September 1933. Officially opened as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford's charter on 16 September 1933. Officially opened as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford's charter on 16 September 1933. – previously Stretford Town Hall – is now the administrative centre of Trafford.[51]

Political representation

The parliamentary constituency of Stretford was created in 1885 as a result of the Redistribution of Seats Act that year,[52] which introduced the concept of equally populated constituencies.[53] It existed until 1997, when it was replaced by the present constituency of Stretford and Urmston, which has been represented by the Labour Party since its creation.[54]

The area historically known as Stretford, between the River Irwell in the north and the River Mersey in the south, has since 2023 been divided between the Trafford local government wards of Gorse Hill and Cornbrook, Longford, Lostock and Barton, Old Trafford, and Stretford and Humphrey Park.[55] Each ward is represented by three local councillors, elected in thirds on a four-yearly cycle.[56]

Demographics

Census data: Stretford

As at the 2011 Census, the built-up areaCategorisation of UK census data that corresponds more closely to the traditional towns, villages and cities that people associate with where they live than do the administrative boundaries. of Stretford has a population of 26,813, with a median age of 37.3 years. The area occupies 453.5 hectares (1,120.6 acres), giving a population density of 59.1 persons per hectare.[57]

Economy

Until the end of the 19th century Stretford was a largely agricultural village. The development of the Trafford Park industrial estate in the north of the town, beginning in the late 19th century, had a significant effect on Stretford’s subsequent development. At its peak in 1945 the park employed an estimated 75,000 workers,[58] and housing and other amenities had to be constructed on what had previously been agricultural land.[59] Trafford Park remains a very significant source of employment, containing an estimated 1,400 companies and employing about 40,000 people.[1]

Stretford Mall, described in Pevsner’s The Buildings of England series as a “dispiriting 1970s shopping centre”,[2] is the main commercial and retail centre, opened in 1969 as the Stretford Arndale,[60] and subsequently renamed.[61] The mall was built on the site of the town’s original shopping centre in the former King Street, which as at 2022 there are plans to restore as part of a wide-ranging redevelopment scheme.[62] The Trafford Centre, a large shopping and leisure complex opened in September 1998,[63] lies about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) to the northwest of Stretford.

Landmarks

Imperial War Museum North

Main article: Imperial War Museum NorthMuseum in the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford in Greater Manchester, England. One of five branches of the Imperial War Museum, it explores the impact of modern conflicts on people and society.

Designed by the Berlin-based architect Daniel Libeskind and opened in July 2002,[64] the Imperial War Museum North is one of five branches of the Imperial War Museum and the first to be located in the north of England.[65] Overlooking the Manchester Ship Canal in Trafford Park, the museum explores the impact of modern conflicts on people and society. The building represents a globe shattered into fragments and then reassembled. Each of the three interlocking fragments – representing earth, air and water – form a functionally distinct part of the museum.[66]

Longford Cinema

Main article: Longford CinemaCinema opposite Stretford Mall on the eastern side of the A56 Chester Road, perhaps the most visually striking building in the town.

Designed by the architect Henry Elder, Longford Cinema was the height of Art Deco fashion when it was opened by the Mayor of Stretford in 1936. Its unusual “cash register” frontage was intended to symbolise the business aspect of show business.[67]

Vacant since 1995 despite Trafford Council’s repeated efforts to bring the building back into active use, the council has proposed its redevelopment as part of the masterplan for the area.[61]

Cenotaph

Stretford Cenotaph, opposite the Chester Road entrance to Gorse Hill Park, was built as a memorial to the 584 Stretford men who lost their lives in the First World War. Their names and regiments are listed on a large bronze plaque on the semi-circular 36-metre (118 ft) wall behind the cenotaph. It was formally unveiled in 1923 by the Earl of Derby, Secretary of State for War.[68]

The cenotaph, made of Darley Dale stone by the sculptors J. and M. Patterson, is 7.9 metres (25.9 ft) high and 3.3 metres (10.8 ft) wide at its base.[68] It cost £2,000 to build, raised by public subscription and a donation from the Stretford Red Cross.[69] The memorial bears the legend “They died that we might live” on one side, and “In memory of the heroic dead” on the other. It is a Grade II listed structure.[70]

Stretford Cemetery

Stretford Cemetery was designed by John Shaw and opened in 1885. Its chapel is in the Decorated style, designed by architects Bellamy & Hardy, and quite elaborate.[71] In 1948 a memorial to the casualties of those residents of Stretford killed during the Manchester BlitzHeavy bombing of the city of Manchester and its surrounding areas in North West England during the Second World War by the Nazi German Luftwaffe. of December 1940, including seventeen unidentified persons, was erected over their communal grave.[72]

Stretford Public Hall

Main article: Stretford Public HallPublic hall built in 1878 by the Manchester's first multi-millionaire John Rylands.

Stretford Public Hall was built in 1878 by John RylandsJohn Rylands (7 February 1801 – 11 December 1888) was an English entrepreneur and philanthropist. He was the owner of the largest textile manufacturing concern in the United Kingdom, and Manchester’s first multi-millionaire. , Manchester’s first multi-millionaire and a local benefactor.[73] It was designed by N. Lofthouse and is on the western side of the A56 Chester Road, opposite the Longford Cinema.[74] On the death of Rylands in 1888, his widow placed the building at the disposal of the local authority for a nominal rent; on her own death in 1908 the building was bought by Stretford Council for £5,000.[73]

The building re-opened in March 1949 as the Stretford Civic Theatre, with a well-equipped stage for the use of local groups, but fell into disrepair despite being designated a Grade II listed structure in 1987.[75] Trafford Council refurbished and converted the hall to serve as council offices in the mid-1990s. It was re-opened in 1997, once again named Stretford Public Hall,[76] and is now in the possession of Friends of Stretford Public Hall, a charitable Community Benefit Society.[77]

Trafford Town Hall

Main article: Trafford Town HallOfficially opened as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford's charter on 16 September 1933. Officially opened as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford's charter on 16 September 1933. Officially opened as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford's charter on 16 September 1933.

Trafford Town Hall stands in a large site at the junction of Talbot Road and Warwick Road, directly opposite the Old Trafford Cricket Ground. It was designed in the Neo-classical style by the architects Bradshaw Gass & Hope of Bolton.[51]

The town hall officially came into use as Stretford Town Hall on the granting of Stretford’s charter, on 16 September 1933. In 1974, on the formation of the new Trafford Metropolitan Borough, Stretford Town Hall was adopted as the home of the new council and renamed Trafford Town Hall; it was designated a Grade II listed building in 2007.[51]

The Great Stone

Main article: The Great Stone, StretfordGrade II listed structure in Stretford, Greater Manchester, probably the base of an Anglo-Saxon cross shaft.

A Grade II listed glacial erraticRocks that differ from the type native to an area. now situated at the Chester Road entrance to Gorse Hill Park. It may have been a marker on the Roman road between Northwich and Manchester, or some kind of boundary marker.[78] It is also thought to have been the base of an Anglo-Saxon cross shaft,[79] and may have been used as a plague stoneHollowed out stones or boulders containing vinegar to disinfect coins, usually placed at or near parish boundaries, relics of medieval plagues.,[80] during the succession of plagues in Manchester from the 14th century onwards.[81]

Union Baptist Church

Main article: Union Baptist Church, StretfordGrade II listed former Union Baptist Church in Stretford, Greater Manchester, opened in 1867 and owned by the Iglesia ni Cristo since 2012.

Grade II listed church opened in 1867 by its patron, the textile magnate and philanthropist John RylandsJohn Rylands (7 February 1801 – 11 December 1888) was an English entrepreneur and philanthropist. He was the owner of the largest textile manufacturing concern in the United Kingdom, and Manchester’s first multi-millionaire. .[71] It was converted into office accommodation in the late 20th century, but reverted to its intended religious use following its purchase in 2012 by the Iglesia ni Cristo.[82]

Transport

Stretford Metrolink station is part of the Manchester Metrolink tram system, lying on the Altrincham to Bury line.[42] The nearest main-line railway station is Trafford Park on the edge of the industrial estate, on the Liverpool to Manchester line operated by Northern Trains.[83] The 20-acre (8 ha) Trafford Park Euroterminal rail freight terminal, opened in 1993, is in the Gorse Hill area of Stretford. It cost £11 million and has the capacity to deal with 100,000 containers a year. Containers are handled by two huge gantry cranes, the noise from which has led to complaints from some local residents.[84]

The town has good access to the motorway network. Junction 7 of the M60 is just to the north of Stretford’s boundary with Sale, and the A56 road gives easy access to the south as well as to Manchester city centre in the other direction.

Existing cycle paths throughout Stretford and Salford QuaysArea of Salford, Greater Manchester, England at the terminus of the Manchester Ship Canal. Previously the site of Manchester Docks, also known as Salford Docks, it became one of the first and largest urban regeneration projects in the United Kingdom following the closure of the dockyards in 1982. are being extended as part of Greater Manchester’s Bee Network.[85]

Manchester Airport, the busiest in the UK outside London,[86] is about nine miles (14 km) to the south of Stretford.

Education

Along with the rest of Trafford, Stretford maintains a selective education system assessed by the 11-plus examination.[87] Of the twenty-six secondary schools in Trafford,[88] four are in Stretford, one of which – Stretford Grammar School – operates the selective system.[89]

University Academy 92, opened in 2019,[90] is a higher education institution co-founded by Lancaster University and members of the Class of ’92, the Manchester United football players who won the 1992 FA Youth Cup,[91][c]Gary Neville, Phil Neville, Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes and Nicky Butt.[91] with the aim of attracting students who might otherwise not go on to higher education.[92] The main campus in Old Trafford is close to Manchester United’s football stadium and Lancashire County Cricket Club’s ground, both of which clubs the university has partnerships with.[92]

Churches

Stretford is in the Roman Catholic Diocese of Salford,[93] and the Anglican Diocese of Manchester.[94] The date of the first church to be built in Stretford is unrecorded, but in a lease dated 1413, land is described as lying next to a chapel.[6] Methodism was a significant influence in 19th-century Stretford,[95] and the Catholic mission in the town was begun in 1859, in a small chapel on Herbert Street.[96]

There are two Grade II listed churches in Stretford: the Church of St AnnActive Roman Catholic church in Stretford, Greater Manchester, a designated Grade II listed building completed in 1867.[97] and the Church of St MatthewActive Anglican church in Stretford, Greater Manchester, built in 1841–1842..[98] St Ann’s is a Roman Catholic church, built in 1862–1867 by Edward Welby Pugin for Sir Humphrey and Lady Annette de Trafford.[97] It was officially opened by Bishop William Turner on 22 November 1863, and was consecrated in June 1867.[99] Features include a historic organ built by Jardine & Co (1867) and a good number of fine stained glass windows by Hardman & Co of Birmingham. St Matthew’s was built in 1842 by W. Hayley in the Gothic Revival style, with additional phases in 1869, 1906 and 1922.[98]

St Antony of Padua, on Eleventh Street in Trafford Park, is a rare surviving example of a tin tabernaclePrefabricated ecclesiastical buildings made from corrugated galvanised iron, developed in the mid-19th century initially in Great Britain, built in Britain and exported across the world. ,[101] a type of prefabricated building constructed from sheets of corrugated iron.[102] The only survivor of three built in the park,[103] it contains the altar and a stained glass window from the chapel at Trafford Hall, donated by Lady Annette de Trafford.[104]

Sport

Stretford has been the home of Manchester United Football Club since 1910, when the club moved to its present Old Trafford ground, the largest football stadium in the UK, the western end of which is still unofficially called the Stretford End.[105][d]It is officially known as the West End.

Old Trafford was originally the home of Manchester Cricket Club, but became the home of Lancashire County Cricket Club in 1864 upon that club’s formation. The ground is on Talbot Road, Stretford, where it has been since 1856. Similar to its counterpart, one end of the Old Trafford cricket ground is called the Stretford End. It has been a Test venue since 1884 and has hosted three World Cup semi-finals.[106]

Stretford Sports Village consists of three centres, offering a 25-metre swimming pool, gyms and other sports facilities. They are the Chester Centre, formerly known as Stretford Leisure Centre, the Talbot Centre at Stretford High School, and the Sports Barn in Old Trafford.[107]

Longford Park Stadium, adjoining Longford Park, is the home of Trafford Athletic Club, founded in 1964 as Stretford Athletic Club.[108] Members have included the Olympic sprinter Paula Dunn, the hurdler Shirley Strong, Olympic silver medallist in 1984,[109] and Craig Wheeler, who holds the record for the fastest mile ever run.[108][e]Wheeler set a time of 3:24.00 in 1993,[108] but that record has not been officially recognised because the course was downhill.[110]

Notes

| a | A local dish known as Stretford Goose consisted of pork stuffed with sage and onions.[3] |

|---|---|

| b | The Rolls-Royce Merlin engine was made by Ford, under licence. The factory produced 34,000 engines, and employed 17,316 people.[31] |

| c | Gary Neville, Phil Neville, Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes and Nicky Butt.[91] |

| d | It is officially known as the West End. |

| e | Wheeler set a time of 3:24.00 in 1993,[108] but that record has not been officially recognised because the course was downhill.[110] |

References

- p. 647

- p. 20

- p. 44

- pp. 20–21

- p. 177

- p. 6

- p. 12

- p. 13

- p. 15

- p. 38

- pp. 39, 57

- p. 97

- p. 105

- pp. 19–20

- p. 23

- p. 107

- pp. 107–110

- p. 129

- p. xiii

- p. 24

- pp. 103–104

- pp. 139–141

- p. 97

- p. 54

- p. 25

- p. 58

- pp. 36, 40

- pp. 63–65

- p. 122

- pp. 88–89

- p. 89

- p. 199

- pp. 130–133

- p. 43

- p. 55

- p. 131

- p. 652

- p. 156

- p. 83

- p. 118

- p. 87

- p. 86

- p. 161

- p. 11

- p. 126

- p. 127

- p. 651

- p. 40

- p. 150