The Manchester Ship Canal is a 36-mile-long (58 km) inland waterway in the North West of England linking Manchester to the Irish Sea. Starting at the Mersey Estuary near Liverpool, it generally follows the original routes of the rivers Mersey and Irwell through the historic counties of Cheshire and Lancashire. Several sets of locks lift vessels about 60 feet (18 m) up to Manchester, where the canal’s terminus was built. Major landmarks along its route include the Barton Swing AqueductAqueduct in Barton upon Irwell, Greater Manchester, England carrying the Bridgewater Canal across the Manchester Ship Canal, opened in 1894.Aqueduct in Barton upon Irwell, Greater Manchester, England carrying the Bridgewater Canal across the Manchester Ship Canal, opened in 1894., the only swing aqueduct in the world, and Trafford ParkFirst planned industrial estate in the world, and still the largest in Europe., the world’s first planned industrial estate and still the largest in Europe.

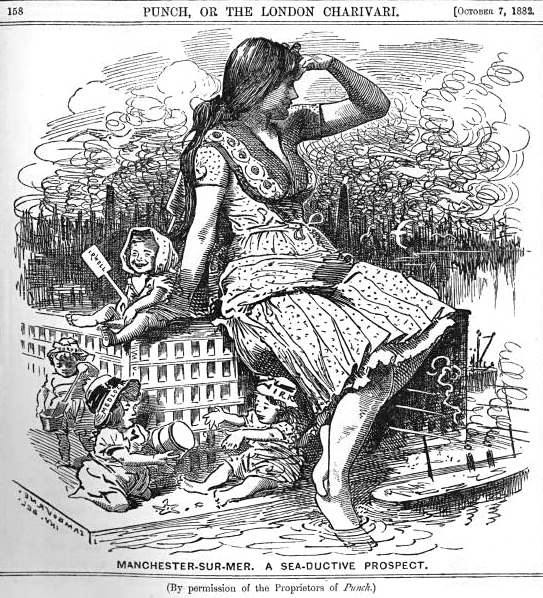

The rivers Mersey and Irwell were first made navigable in the early 18th century. Goods were also transported on the Runcorn extension of the Bridgewater Canal (from 1776) and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (from 1830), but by the late 19th century the Mersey and Irwell Navigation had fallen into disrepair and was often unusable. In addition, Manchester’s business community viewed the charges imposed by Liverpool’s docks and the railway companies as excessive. A ship canal was therefore proposed as a way of giving ocean-going vessels direct access to Manchester. The region was suffering from the effects of the Long Depression, and for the canal’s proponents, who argued that the scheme would boost competition and create jobs, the idea of a ship canal made sound economic sense. They initiated a public campaign to enlist support for the scheme, which was first presented to Parliament as a bill in 1882. Faced with stiff opposition from Liverpool, the canal’s supporters were unable to gain the necessary Act of Parliament to allow the scheme to go ahead until 1885.

Construction began in 1887; it took six years and cost £15 million, equivalent to about £1.7 billion as at 2018.[a]Comparing project costs using the GDP deflator calculation at Measuring Worth.[1] When the ship canal opened in January 1894 it was the largest river navigation canal in the world, and enabled the newly created Port of Manchester to become Britain’s third busiest port despite the city being about 40 miles (64 km) miles (64 km) inland. Changes to shipping methods and the growth of containerisation during the 1970s and ’80s meant that many ships were now too big to use the canal and traffic declined, resulting in the closure of the terminal docks at Salford. Although able to accommodate a range of vessels from coastal ships to intercontinental cargo liners, the canal is not large enough for most modern vessels. By 2011 traffic had decreased from its peak in 1958 of 18 million tons of freight each year to about 7 million tons.

The canal is now privately owned by Peel Ports, whose plans include the construction of four million square feet (371,613 m2) of warehousing and logistics facilities,[2] as part of their Atlantic Gateway Project.[3]

History

Early history

The idea that the rivers Mersey and Irwell should be made navigable from the Mersey Estuary in the west to Manchester in the east was first proposed in 1660, and revived in 1712 by the English civil engineer Thomas Steers.[4] The necessary legislation was proposed in 1720, and the Act of Parliament for the navigation passed into law in 1721.[5][6] Construction began in 1724, undertaken by the Mersey & Irwell Navigation Company.[4] By 1734 boats “of moderate size” were able to make the journey from quays near Water Street in Manchester to the Irish Sea,[7] but the navigation was only suitable for small ships; during periods of low rainfall or when strong easterly winds held back the tide in the estuary, there was not always sufficient depth of water for a fully laden boat.[8] The completion in 1776 of the Runcorn extension of the Bridgewater Canal, followed in 1830 by the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, intensified competition for the carriage of goods. In 1825 an application had been made to Parliament for an Act to allow the construction of a ship canal between the mouth of the River Dee and Manchester at a cost of £1 million, but “the necessary forms not having been observed”, it did not become law.[9] In 1844 ownership of the Mersey & Irwell Navigation was transferred to the Bridgewater Trustees, and in 1872 it was sold to The Bridgewater Navigation Company for £1.112 million.[10] The navigation had by then fallen into disrepair, its owners preferring instead to maintain the more profitable canal;[11] in 1882 the navigation was described as being “hopelessly choked with silt and filth”, and was closed to all but the smaller boats for 264 out of 311 working days.[10]

Wikimedia Commons

Along with deteriorating economic conditions in the 1870s[12] and the start of a period known as the Long Depression, the dues charged by the Port of Liverpool and the railway charges from there to Manchester were perceived to be excessive by Manchester’s business community; it was often cheaper to import goods from Hull, on the opposite side of the country, than it was from Liverpool.[13] A ship canal was proposed as a way to reduce carriage charges, avoid payment of dock and town dues at Liverpool, and bypass the Liverpool to Manchester railways by giving Manchester direct access to the sea for its imports and its exports of manufactured goods.[14] Historian Ian Harford suggested that the canal may also have been conceived as an “imaginative response to [the] problems of depression and unemployment”[15] that Manchester was experiencing during the early 1880s. Its proponents argued that reduced transport costs would make local industry more competitive, and that the scheme would help create new jobs.[16]

The idea was championed by Manchester manufacturer Daniel Adamson, who arranged a meeting at his home, The Towers in Didsbury, on 27 June 1882. He invited the representatives of several Lancashire towns, local businessmen and politicians, and two civil engineers: Hamilton Fulton and Edward Leader Williams. Fulton’s design was for a tidal canal, with no locks and a deepened channel into Manchester. With the city about 60 feet (18 m) above sea level, the docks and quays would have been well below the surrounding surface. Williams’ plan was to dredge a channel between a set of retaining walls, and build a series of locks and sluices to lift incoming vessels up to Manchester.[17] Both engineers were invited to submit their proposals, and Williams’ plans were selected to form the basis of a bill to be submitted to Parliament later that year.[18]

Public campaign

To generate support for the scheme, the provisional committee initiated a public campaign led by Joseph Lawrence, who had worked for the Hull and Barnsley Railway. His task was to set up committees in every ward in Manchester and throughout Lancashire, to raise subscriptions and sell the idea to the local public. The first meeting was held on 4 October in Manchester’s Oxford Ward, followed by another on 17 October in the St. James Ward. Within a few weeks meetings had been held throughout Manchester and Salford, culminating in a conference on 3 November attended by the provisional committee and members of the various Ward Committees. A large meeting of the working classes, attended by several local notables including the general secretaries of several trade unions, was held on 13 November at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester.[19]

Regular night-time meetings were held across the region, headed by speakers from a range of professions. Harford suggests that the organisers’ choice of orators represents their “canny ability”[20] to choose speakers who might move their audiences to support their cause. By adopting techniques used by the Anti-Corn Law League, their strategy was ultimately successful: local offices were acquired, secretaries hired and further meetings organised. The weekly Ship Canal Gazette, priced at one penny,[21] was by the end of the year being sold at newsagents in towns across Lancashire.[22] The Gazette was part of a prolonged print campaign organised by the committee, to circulate leaflets and pamphlets, and write supportive letters to the local press, often signed with pseudonyms.[23] One of the few surviving leaflets, “The Manchester Ship Canal. Reasons why it Should be Made”, argued against dock and railway rates, which were apparently levied “with the object of protecting the interests of Railway kings, [so that] trade is handicapped, and wages kept low”.[24] By the end of 1882 the provisional committee comprised members from several of Manchester’s large industries, but notably few of the city’s wealthier inhabitants. The sympathetic Manchester City News reported that “the rich men of South and East Lancashire, with a few notable exceptions, have not rivalled the enthusiasm of the general public”.[20]

Bills

Wikipedia

The Mersey Docks Board opposed the committee’s first bill, presented late in 1882, and it was rejected by Parliament in January 1883 for breaching Standing Orders. Within six weeks the committee organised hundreds of petitions from a range of bodies across the country: one representing Manchester was signed by almost 200,000 people. The requirement for Standing Orders was dispensed with, and the represented bill allowed to proceed. Some witnesses against the scheme, worried that a canal would cause the entrance to the Mersey estuary to silt up, blocking traffic, cited the case of Chester harbour. This had silted up owing to a man-made cut through the Dee estuary. Faced with conflicting evidence, Parliament rejected the bill.[26] Later mass meetings were held, including a large demonstration at Pomona Gardens on 24 June 1884. Strong opposition from Liverpool led the House of Commons Committee to reject the committee’s second bill on 1 August 1884.[27]

The unresolved question of what would happen to the Mersey estuary if the canal was built had remained a sticking point. During questioning, an engineer for the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board was asked how he would avoid such a problem. His reply, “I should enter at Eastham and carry the canal along the shore until I reached Runcorn, and then I would strike inland”,[28] prompted Williams to change his design to include this suggestion.[26] Despite continued opposition, the committee’s third bill, presented in November 1884, was passed by Parliament on 2 May 1885, and received royal assent on 6 August, becoming the Manchester Ship Canal Act 1885. Certain conditions were attached: £5 million had to be raised, and the ship canal company was legally obliged to buy the Bridgewater Canal and the Mersey & Irwell Navigation within two years.[29] The estimated cost of construction was £5.16 million, and the work was expected to take four years to complete.[18]

Financing

The enabling Act of Parliament stipulated that the ship canal company’s £8 million share capital had to be issued within two years, otherwise the act would lapse.[30] Adamson wanted to encourage the widest possible share ownership, and believed the funds should be raised largely from the working population. Richard Peacock, vice-chairman of the Provisional Manchester Ship Canal Committee, said in 1882:

The Act forbade the company from issuing shares below £10 so, to make them easier for ordinary people to buy, they issued shilling coupons in books of ten so they could be paid for in instalments.[32] The construction costs and expected competition from the Port of Liverpool put off potential investors; by May 1887 only £3 million had been raised. As a temporary solution Thomas Walker, the contractor selected to construct the canal, agreed to accept £500,000 of the contract price in shares, but raising the remainder required another Act of Parliament to allow the company’s share capital to be restructured as £3 million of ordinary shares and £4 million of preference shares.[30] Adamson was convinced that the money should be raised from members of the public and opposed the debt restructuring, resigning as chairman of the Ship Canal Committee on 1 February 1887. Barings and Rothschild jointly issued a prospectus for the sale of the preference shares on 15 July, and by 21 July the issue had been fully underwritten, allowing construction to begin.[30][33] The first sod was cut on 11 November 1887, by Lord Egerton of Tatton, who had taken over the chairmanship of the Manchester Ship Canal Company from Adamson.[34]

The canal company exhausted its capital of £8 million in 4 years, when only half the construction work was completed. To avoid bankruptcy they appealed for funds to Manchester Corporation, which set up a Ship Canal Committee. On 9 March 1891 the corporation decided, on the committee’s recommendation, to lend the necessary £3 million, to preserve the city’s prestige. In return the corporation was allowed to appoint five of the fifteen members of the board of directors. The company subsequently raised its estimates of the cost of completion in September 1891 and again in June 1892. An executive committee was appointed as an emergency measure in December 1891, and on 14 October 1892 the Ship Canal Committee resolved to lend a further £1.5 million on condition that Manchester Corporation had an absolute majority on the canal company’s board of directors and its various sub-committees.[35] The corporation subsequently appointed 11 of the 21 seats,[36] nominated Alderman Sir John Harwood as deputy director of the company, and secured majorities on five of the board’s six sub-committees. The cost to Manchester Corporation of financing the Ship Canal Company had a significant impact on local taxpayers. Manchester’s municipal debt rose by 67 per cent, resulting in a 26 per cent increase in rates between 1892 and 1895.[37]

However well this arrangement served the corporation, by the mid-1980s it had become “meaningless”. Most of the company’s shares were controlled by the property developer John Whittaker, and in 1986 the council agreed to give up all but one of its seats in return for a payment of £10 million. The deal extricated Manchester Council from a politically difficult conflict of interest, as Whittaker was proposing to develop a large out of town shopping centre on land owned by the Ship Canal Company at Dumplington, the present-day Trafford Centre. The council opposed the scheme, believing that it would damage the city centre economy, but accepted that it was “obviously in the interests of the shareholders”.[38][b]£7 million was paid in cash and £3 million invested in a joint venture company set up by Whittaker and the council, Ship Canal Developments. The object of the new company was to provide resources and development expertise for the regeneration of east Manchester.[39]

Construction

Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Walker was appointed as contractor, with Edward Leader Williams as chief engineer and designer and general manager. The 36-mile (58 km) route was divided into eight sections, with one engineer responsible for each. The first reached from Eastham to Ellesmere Port. Mount Manisty, a large mound of earth on a narrow stretch between the canal and the Mersey northwest of Ellesmere Port, was constructed from soil taken from the excavations. It and the adjacent Manisty Cutting were named after the engineer in charge. The last section built was the passage from Weston Point through the Runcorn gap to Norton; the existing docks at Runcorn and Weston had to be kept operational until they could be connected to the completed western sections of the ship canal.[40]

For the first two years construction went according to plan, but Walker died on 25 November 1889. The work was continued by his executors, but the project suffered setbacks and was hampered by harsh weather and several serious floods. In January 1891, when the project had been expected to have been completed, a severe winter added to the difficulties; the Bridgewater Canal, the company’s only source of income, was closed after a fall of ice. The company decided to take over the contracting work and bought all the on site equipment for £400,000.[41] Some railway companies, whose bridges had to be modified to cross the canal, demanded compensation. The London and North Western Railway and Great Western Railway refused to cooperate, and between them they demanded about £533,000 for inconvenience. The Ship Canal Company was unable to demolish the older, low railway bridges until August 1893, when the matter went to arbitration. The railway companies were awarded just over £100,000, a fraction of their combined claims.[42]

By the end of 1891, the ship canal was open to shipping as far as Saltport, the name given to wharves built at the entrance to the Weaver Navigation. The success of the new port was a source of consternation to merchants in Liverpool, who suddenly found themselves cut out of the trade in goods such as timber, and a source of encouragement to shipping companies, who began to realise the advantages an inland port would offer.[43] Saltport was rendered useless when the ship canal was completely filled with water in November 1893. The Manchester Ship Canal Police were formed the following month,[44] and the canal opened to its first traffic on 1 January 1894. On 21 May, Queen Victoria performed the official opening,[45] the last of three royal visits she made to Manchester. During the ceremony she knighted the Mayor of Salford, William Henry Bailey, and the Lord Mayor of Manchester, Anthony Marshall; Edward Leader Williams was knighted on 2 July by letters patent.[46]

The ship canal took six years to complete at a cost of just over £15 million,[47] equivalent to about £1.7 billion as at 2018.[c]Comparing project costs using the GDP deflator calculation at Measuring Worth.[1] It is still the longest river navigation canal[48] and remains the world’s eighth-longest ship canal, only slightly shorter than the Panama Canal in Central America.[49] More than 54 million cubic yards (41,000,000 m³) of material were excavated, about half as much as was removed during the building of the Suez Canal.[50] An average of 12,000 workers were employed during construction, peaking at 17,000.[51] Regular navvies were paid 4 ½d per hour for a 10-hour working day, equivalent to about £20 per day as at 2018.[52][d]Using the change in the retail price index.[1] In terms of machinery, the project made use of more than 200 miles (322 km) of temporary rail track, 180 locomotives, more than 6000 trucks and wagons, 124 steam-powered cranes, 192 other steam engines, and 97 steam excavators.[53][54] Major engineering landmarks included the Barton Swing AqueductAqueduct in Barton upon Irwell, Greater Manchester, England carrying the Bridgewater Canal across the Manchester Ship Canal, opened in 1894.Aqueduct in Barton upon Irwell, Greater Manchester, England carrying the Bridgewater Canal across the Manchester Ship Canal, opened in 1894., the first and only swing aqueduct in the world,[55] and a neighbouring swing bridge for road traffic at Barton, both of which are now Grade II* listed structures.[56] In 1909 the canal’s depth was increased by 2 feet (1 m) to 28 feet (9 m), equalling that of the Suez Canal.[57]

Operational history

The Manchester Ship Canal enabled the newly created Port of ManchesterCustoms port in North West England, created on 1 January 1894 and closed in 1982. to become Britain’s third-busiest port, despite the city being about 40 miles (64 km) inland.[49] Since its opening in 1894 the canal has handled a wide range of ships and cargos, from coastal vessels to intra-European shipping and intercontinental cargo liners. The first vessel to unload its cargo on the opening day was the Pioneer, belonging to the Co-operative Wholesale Society (CWS), which was also the first vessel registered at Manchester; the CWS operated a weekly service to Rouen.[58]

Manchester LinersCargo and passenger shipping company founded in 1898, based in Manchester, England. established regular sailings by large ocean-going vessels. In late 1898 the Manchester City, at 7,698 gross tons, became the largest vessel to reach the terminal docks. Carrying cattle and general cargo, it was met by the Lord Mayor of Manchester and a large welcoming crowd.[59] In 1968 Manchester Liners converted its fleet to container vessels only. To service them it built two dedicated container terminals next to No. 9 Dock.[60] The four container vessels commissioned that year, each of 11,898 gross tons, were the largest ever to make regular use of the terminal docks at Salford.[61] In 1974 the canal handled 2.9 million tons of dry cargo, 27 per cent of which was carried by Manchester Liners.[62] The dry tonnage was, and is still, greatly supplemented by crude and refined oil products transported in large tanker ships to and from the Queen Elizabeth II Dock at Eastham and the Stanlow Refinery just east of Ellesmere Port, and also in smaller tankers to Runcorn. The limitations imposed by the canal on the maximum size of container vessel meant that by the mid-1970s Manchester Liners was becoming uncompetitive; the company sold its last ship in 1985.[63]

| Tonnage handled by Manchester Ship Canal ports | |||||

| 1895 | 1905 | 1915 | 1925 | 1935 | 1945 |

| 1,358,875 | 3,060,516 | 5,434,046 | 5,881,691 | 6,135,003 | 6,531,963 |

| 1955 | 1965 | 1975 | 1985 | 1995 | 2005 |

| 18,563,376 | 15,715,409 | 14,816,121 | 9,767,380 | 8,751,938 | 7,261,919 |

The amount of freight carried by the canal peaked in 1958 at 18 million tons, but the increasing size of ocean-going ships and the port’s failure to introduce modern freight-handling methods resulted in that headline figure dropping steadily, and the closure of the docks in Salford in 1984.[64] Total freight movements on the ship canal were down to 7.56 million tons by 2000, and further reduced to 6.6 million tons for the year ending September 2009.[65]

The maximum length of vessel currently accepted is 530 feet (161.5 m) with a beam of 63.5 feet (19.35 m)[66] and a maximum draft of 24 feet (7.3 m).[61] By contrast the similarly sized Panama Canal, completed a few years after the Manchester Ship Canal, was able to accept ships of up to 950 feet (289.6 m) in length with a beam of 106 feet (32.31 m).[71] In comparison, the Panama Canal can handle vessels of 1201 feet (366 m) in length with a beam of 161 feet (49 m) and a draft of 50 feet (15 m).[67] Ships passing under the Runcorn Bridge have a height restriction of 70 feet (21 m) above normal water levels.[68]

Present day

The canal was completed just as the Long Depression was coming to an end,[69] but it was never the commercial success its sponsors had hoped for. At first gross revenue was less than a quarter of expected net revenue, and throughout at least the first nineteen years of the canal it was unable to make a profit or meet the interest payments to the Corporation of Manchester.[70] Many ship owners were reluctant to dispatch ocean-going vessels along a “locked cul-de-sac” at a maximum speed of 6 knots (11 km/h; 6.9 mph). The Ship Canal Company found it difficult to attract a diversified export trade, which meant that ships frequently had to return down the canal loaded with ballast rather than freight. The only staple imports attracted to the Port of Manchester were lamp oil and bananas, the latter from 1902 until 1911. As the import trade in oil began to grow during the 20th century the balance of canal traffic switched to the west, from Salford to Stanlow, eventually culminating in the closure of the docks at Salford. The historian Thomas Stuart Willan has observed that “What may seem to require explanation is not the comparative failure of the Ship Canal but the unquenchable vitality of the myth of its success”.[71]

Unlike most other British canals, the Manchester Ship Canal was never nationalised. In 1984 Salford City Council used a derelict land grant to purchase the docks at Salford from the Ship Canal Company,[72] rebranding the area as Salford Quays. Traffic on the canal’s upper reaches had by then declined to such an extent that its owners considered closing it above Runcorn.[73] In 1993 the Ship Canal Company was acquired by Peel Holdings,[74] and is now owned and operated by Peel Ports, which also owns the Port of Liverpool.[2] The company announced an Atlantic Gateway plan in 2011 to develop the Port of Liverpool and the Manchester Ship Canal as a way of combating increasing road congestion and unlocking the area’s growth potential.[3]

Route

Geography

From Eastham the canal runs parallel to, and along the south side of the Mersey estuary, past Ellesmere Port. Between Rixton east of the M6 motorway’s Thelwall Viaduct and Irlam, the canal joins the Mersey; thereafter it roughly follows the route the river used to take. At the confluence of the Mersey and the Irwell near Irlam, the canal follows the old course of the River Irwell into Manchester.[75]

Locks, sluices and weirs

Vessels travelling to and from the terminal docks, which are 60 feet (18 m) above sea level, must pass through several locks. Each set has a large lock for ocean-going ships and a smaller, narrower lock for vessels such as tugs and coasters.[76] The entrance locks at Eastham on the Wirral side of the Mersey, which seal off the tidal estuary, are the largest on the canal. The larger lock is 600 feet (180 m) long by 80 feet (24 m) wide; the smaller lock is 350 feet (110 m) by 50 feet (15 m). Four additional sets of locks lie further inland, 600 feet (180 m) long and 65 feet (20 m) wide and 350 feet (110 m) by 45 feet (14 m) for the smaller lock;[77] each has a rise of approximately 15 feet (4.6 m). The locks are at Eastham; Latchford, near Warrington; Irlam; Barton near Eccles and Mode Wheel, Salford.[76]

Five sets of sluices and two weirs are used to control the canal’s depth. The sluices, located at Mode Wheel Locks, Barton Locks, Irlam Locks, Latchford Locks and Weaver Sluices, are designed to allow water entering the canal to flow along its length in a controlled manner. Each consists of a set of mechanically driven vertical steel roller gates, supported by masonry piers. The original manually operated Stoney Sluices[e]A Stoney Sluice gate runs on bearings, reducing the friction caused by the weight of water on the gate. were replaced in the 1950s by electrically driven units, with automation technology introduced from the late 1980s. The sluices are protected against damage from drifting vessels by large concrete barriers. Stop logs can be inserted by roving cranes, installed upstream of each sluice; at Weaver Sluices, accessed by boat, this task is performed by a floating crane.[78]

Woolston Siphon Weir, built in 1994 to replace an earlier structure and located on an extant section of the Mersey near Latchford, controls the amount of water in the Latchford Pond by emptying canal water into the Mersey. Howley Weir controls water levels downstream of Woolston Weir. Further upstream, Woolston Guard Weir enables maintenance to be carried out on both.[78]

Docks and wharves

Seven terminal docks were constructed for the opening of the canal. Four small docks were located on the south side of the canal near Cornbrook, within the Borough of StretfordCreated in 1894 and granted a charter of incorporation in 1933, becoming a municipal borough. Abolished in 1974, the area it controlled is now part of the Metropolitan Borough of Trafford in Greater Manchester.: Pomona Docks No. 1, No. 2, No. 3, and No. 4. The three main docks, built primarily for large ocean-going vessels, were in Salford, to the west of Trafford Road on the north bank of the canal, docks No. 6, No. 7, and No. 8. In 1905, No. 9 Dock was completed on the same site.[79] Dock No. 5, known as Ordsall Dock, was part of Pomona Docks, but was dug on the Salford side of the river; it was never completed and was filled in around 1905.[80]

Pomona Docks have also been filled in except for the still intact No. 3 Dock, and are largely derelict. A lock at No. 3 Dock connects it to the nearby Bridgewater Canal at the point where the two waterways run in parallel. The western four docks have been converted into the Salford Quays development; ships using the Manchester Ship Canal now dock at various places along the canal side such as Mode Wheel (Salford), Trafford Park, and Ellesmere Port.[81] Most ships have to terminate at Salford Quays, although vessels capable of passing under Trafford Road swing bridge (permanently closed in 1992) can continue up the River Irwell to Hunts Bank, near Manchester Cathedral.[82][83]

In 1893 the Ship Canal Company sold a parcel of land just east of the Mode Wheel Locks to the newly established Manchester Dry Docks Company. The graving docks were constructed adjacent to the south bank of the canal, and a floating pontoon dock was built nearby.[84] Each of the three graving docks could accommodate ocean-going ships of up to 535 feet (163.1 m) in length and 64 feet (19.5 m) in beam,[85] equivalent to vessels of 8,000 gross tons. Manchester Liners acquired control of the company in 1974, to ensure the availability of facilities for the repair of its fleet of ships.[86]

Trafford Park

Main article: Trafford ParkFirst purpose-built airfield in the Manchester area.

Wikimedia Commons

Two years after the opening of the ship canal, financier Ernest Terah HooleyErnest Terah Hooley (5 February 1859 – 11 February 1947) was an English financier who specialised in acquiring companies and then reselling them at inflated prices, making himself substantial profits in the process. bought the 1183 acres (479 ha)[87] country estate belonging to Sir Humphrey Francis de Trafford for £360,000 (£42 million in 2020).[88][f] Hooley intended to develop the site, which was close to Manchester and at the end of the canal, as an exclusive housing estate, screened by woods from industrial units[89] constructed along the 1.5-mile (2.4 km) frontage onto the canal.[90]

With the predicted traffic for the canal slow to materialise, Hooley and Marshall StevensProperty developer whose work with Daniel Adamson and others led to the construction of the Manchester Ship Canal, completed in 1894. (the general manager of the Ship Canal Company) came to see the benefits that the industrial development of Trafford Park could offer to the ship canal and the estate. In January 1897 Stevens became the managing director of Trafford Park Estates,[89] where he remained until 1930, latterly as its joint chairman and managing director.[91]

Within five years Trafford Park, Europe’s largest industrial estate, was home to forty firms. The earliest structures on the canal side were grain silos; the grain was used for flour and as ballast for ships carrying raw cotton. The wooden silo built opposite No.9 Dock in 1898 (destroyed in the Manchester BlitzHeavy bombing of the city of Manchester and its surrounding areas in North West England during the Second World War by the Nazi German Luftwaffe. in 1940) was Europe’s largest grain elevator. The CWS bought land on Trafford Wharf in 1903, where it opened a bacon factory and a flour mill. In 1906 it bought the Sun Mill, which it extended in 1913 to create the UK’s largest flour mill, with its own wharf, elevators and silos.[92]

Inland from the canal the British Westinghouse Electric Company bought 11 per cent of the estate. Westinghouse’s American architect Charles Heathcote was responsible for much of the planning and design of their factory, which built steam turbines and turbo generators. By 1899 Heathcote had also designed fifteen warehouses for the Manchester Ship Canal Company.[92]

Manchester Ship Canal Railway

Wikimedia Commons

During construction, a year after the death of Walker, the directors of the canal company and Walker’s trustee’s came to an agreement for the canal company to take ownership of the construction assets. These included the more than 200 miles (322 km) of temporary rail track, 180 locomotives and more than 6000 trucks and wagons.[53][54] These formed the basis of the Manchester Ship Canal Railway, which became the largest private railway in the United Kingdom.

The construction railway followed the route of the former River Irwell. To bring in construction materials, the construction railway had a connection to the Cheshire Lines Committee (CLC) east of Irlam railway station. Every month this allowed more than 10,000 tons of coal and 8000 tons of cement to be delivered to sites along the canal excavation. All existing railway companies with lines along the route had been given notice that their lines had to either be abandoned by a given date or raised to give a minimum of 75 feet (23 m) clearance with all deviation construction costs to be paid by the MSC. The CLC Glazebrook to Woodley mainline passed over the River Mersey at Cadishead and so they decided to build a deviation. Construction of the Cadishead Viaduct began in 1892, approached via earth banks, with two brick arches accessing a multi-lattice iron girder centre span of 120 feet (37 m) in length. It opened to freight on 27 February 1893 and to passenger traffic on 29 May 1893.[94]

At the end of construction, the canal company left in place the original construction railway route, and eventually developed track along 33 miles (53 km) of the canal’s length, mainly to its north bank. Built and operated mainly as a single track line, the busiest section from Weaste Junction through Barton and Irlam, to Partington was all double tracked. The railway’s access to Trafford Park was over the double-tracked Detroit Swing Bridge, which after closure of the MSC Railway in 1988 was floated down the canal to be placed in Salford Quays.[95] The only major deviation was to allow construction of the CWS Irlam soap works and the adjacent Partington Steel & Iron Co. works at Partington (both of which had their own private railways and locomotives), with the MSC Railway’s deviation route pushed south to run alongside the canal’s north bank and under the Irlam viaduct. The canal company also developed large complexes of sidings along the route, built to service freight to and from the canal’s docks and nearby industrial estates. Unlike most other railway companies in the UK it was not nationalised in 1948. At its peak, it had 790 employees,[96] 75 locomotives, 2700 wagons and more than 230 miles (370 km) of track.[97]

The MSC Railway was able to receive and despatch goods trains to and from all the UK’s main line railway systems, using connecting junctions at three points in the terminal docks. Two were to the north of the canal, operated by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway and the London and North Western Railway. The third was to the south, operated by the Cheshire Lines Committee (CLC), where by the MSC Railway had taken over the old abandoned CLC route, giving it a monopoly on traffic to the new soap works and steel mill.[96]

The MSC Railway’s steam locomotives were designed to negotiate the tight curves of the sidings and industrial tracks on which they ran. Originally specifying 0-4-0 wheel arrangements, later 0-6-0 locomotives – purchased to cope with increasing traffic and loads – had flangeless centre axles, whilst the coupling rods had a hinged central section that permitted several inches of lateral play. A long-term user of Hudswell Clarke, from their steam through to diesel locomotives,[98] like many industrial railways later motive power was often provided by the purchase of refurbished former “big-four” operated types, with the advantage that crew were readily available to operate them. Post-war purchases included several war surplus Hunslet ‘Austerity’ 0-6-0 saddle tanks, the last steam locomotive types purchased for the MSC Railway. A fleet of diesel locomotives was bought between 1959 and 1966, including 18 0-4-0 diesels from the Rolls-Royce-owned Sentinel Waggon Works from 1964–1966.[99]

As trans-shipment costs increased, and unprocessed bulk cargoes decreased in volume, the economics of road transport led to a gradual decline in traffic on the MSC Railway system.[100] Its last operational section, at Trafford Park, was closed on 30 April 2009.[101]

Other features on the banks

At Ellesmere Port the canal is joined by the Shropshire Union Canal, at a site now occupied by the National Waterways Museum. The area formerly consisted of a 7-acre (3 ha) canal port linking the Shropshire Union Canal to the River Mersey. Designed by Thomas Telford, it remained operational until the 1950s. It was a “marvellously self-contained world” with locks, docks, warehouses, a blacksmith’s forge, stables, and cottages for the workers.[102] A few miles from Ellesmere Port, at Weston, near Runcorn, the ship canal also connects with the Weaver Navigation.[103]

Ecology

The quality of water in the ship canal is adversely affected by several factors. The Mersey Basin’s high population density has historically placed heavy demands on sewage treatment and disposal. Industrial and agricultural discharges into the Irwell, Medlock, and Irk rivers are responsible for industrial contaminants found in the canal. Matters have improved since 1990, when the National Rivers Authority found the area between Trafford Road Bridge and Mode Wheel Locks to be “grossly polluted”. The water was depleted of dissolved oxygen, which in the latter half of the 20th century often resulted in toxic sediments normally present at the bottom of the turning basin in what is now Salford Quays rising to the surface during the summer months, giving the impression of solid ground. Previously, only roach and sticklebacks could be found in the canal’s upper levels, and then only during the colder parts of the year, but an oxygenation project implemented at Salford Quays from 2001, together with the gradual reduction of industrial pollutants from the Mersey’s tributaries, has encouraged the migration into the canal of fish populations from further upstream. The canal’s water quality remains low, with mercury and cadmium in particular present at “extremely high levels”.[104] Episodic pollution and a lack of habitat remain problems for wildlife, although in 2005, for the first time in living memory, salmon were observed breeding in the River Goyt (a part of the Mersey’s catchment). In 2010 the Environment Agency issued a report concluding that the canal “does not pose a significant barrier to salmon movement or impact on migratory behaviours”.[105][106]

Despite the canal’s poor water quality there are several nature reserves along its banks. Wigg Island, a former brownfield site east of Runcorn, contains a network of public footpaths through newly planted woodlands and meadows. A popular bird-watching site, it also supports a rich variety of native wildflowers, including the bee orchid.[107] Further upstream, the Moore Nature Reserve comprises lakes, woodland and meadows. Open to the public, it contains bird hides from which native owls and woodpeckers may be viewed.[108] Near Thelwall, Woolston Eyes is a Site of Special Scientific Interest. It is used as a deposit for canal dredgings and is a habitat for many species of bird, including black-necked grebes, grasshopper warblers, blackcaps and common whitethroats. Great crested newts and adders are present, and local flora includes orchids and broad-leaved helleborines.[109] Diving ducks are regular visitors to Salford Quays, where species including pochard and tufted ducks feed on winter nights.[110]

Notes

| a, c | Comparing project costs using the GDP deflator calculation at Measuring Worth.[1] |

|---|---|

| b | £7 million was paid in cash and £3 million invested in a joint venture company set up by Whittaker and the council, Ship Canal Developments. The object of the new company was to provide resources and development expertise for the regeneration of east Manchester.[39] |

| d | Using the change in the retail price index.[1] |

| e | A Stoney Sluice gate runs on bearings, reducing the friction caused by the weight of water on the gate. |

References

- p. 5

- p. 200

- p. 10

- pp. 3–4

- p. 7

- p. 279

- p. 16

- p. 277

- p. 41

- p. 27

- p. 173

- p. 168

- p. 11

- pp. 121–122

- p. 31

- pp. 21–23

- p. 24

- p. 22

- pp. 24–26

- p. 23

- p. 26

- p. 43

- p. 122

- pp. 26–27

- p. 108

- p. 37

- p. 14

- p. 132

- pp. 38–39

- pp. 42–43

- p. 4

- p. 174

- p. 184

- p. 175

- pp. 98–100

- p. 100

- pp. 46–47

- p. 53

- pp. 61–62

- pp. 59–60

- p. 3

- p. 120

- p. 6

- p. 3

- p. 89

- p. 34

- p. 38

- p. 93

- pp. 117–118

- p. 25

- p. 19

- p. 55

- p. 43

- p. 35

- p. 118

- p. 83

- p. 157

- p. 188

- pp. 179–190

- p. 264

- p. 72

- pp. 132–133

- p. 31

- pp. 80–82

- p. 56

- p. 124

- p. 82

- p. 37

- pp. 57–58

- p. 22

- p. 24

- p. 114

- p. 112

- p. 128

- pp. 143, 145

- p. 101

- p. 57

- p. 108

- pp. 122–123

- p. 77