Astley is a villageSmall rural collection of buildings with a church. in the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, Greater Manchester. Within the boundaries of the historic county of Lancashire, it is crossed by the Bridgewater Canal and the A580 East Lancashire Road. Contiguous with TyldesleyFormer industrial town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, in Greater Manchester., it is equidistant from Wigan and Manchester, both 8.3 miles (13.4 km) away.

Astley’s name is Old English, indicating an Anglo-Saxon settlement. Throughout the Middle Ages, Astley constituted a townshipDivision of an ecclesiastical parish that had civil functions. in the ancient parishAncient or ancient ecclesiastical parishes encompassed groups of villages and hamlets and their adjacent lands, over which a clergyman had jurisdiction. of Leigh and hundred of West Derby. Astley appears in written form as Asteleghe in 1210, when its lord of the manor granted land to Cockersand Abbey.

Medieval and Early Modern Astley is distinguished by the occupants of DamhouseGrade II* listed building in Tyldesley but considered to be in Astley, Greater Manchester, England. It has served as a manor house, sanatorium, and, since restoration in 2000, houses offices, a clinic and tearooms. , the local manor house around which a settlement expanded. The Bridgewater Canal reached Astley in 1795, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830. The Industrial Revolution introduced the factory system when the village’s cotton mill was built in 1833.

Coal mining became an important industry but mining subsidence and a decline in coal production led to a reduction in the industry in the mid-20th century, its cotton mill closed in 1955, and the last coal was brought to the surface in 1970. Astley has grown as part of a commuter belt, supported by its proximity to Manchester city centre and inter-city transport links. Astley Green Colliery Museum houses collections of Astley’s industrial heritage.

Geography

Astley is on the northern side of the Chat MossLarge area of peat bog that makes up 30 per cent of the City of Salford, in Greater Manchester, England bog, about 75 feet (23 m) above sea level.[1] It forms a continuous urban area with TyldesleyFormer industrial town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, in Greater Manchester. to the north. Astley encompasses smaller, suburban and semi-outlying areas, including Blackmoor, Astley Green, Gin Pit and Cross Hillock. The isolated hamlet of terraced houses at Gin Pit was built by the Astley and Tyldesley Collieries Company. Peace Street, Lord Street and Maden Street were named after directors of the company.[2]

Astley is {{convert|8.5|mi} west-northwest of Manchester city centre, and 0.75 miles (1.21 km) north of the Bridgewater Canal, which straddles the village’s southern hinterland from east-to-west. Astley is crossed east-to-west by the A572 and A580 roads. Astley Green lines a straight road leading southwards through Chat Moss, to the former Astley railway station on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway which is 2 miles south of the village.[3]

Astley spans an area of 2,685 acres, of which 1,000 acres is peat bog.[4] Astley and Bedford Mosses

Areas of peat bog south of the Bridgewater Canal and north of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in Astley and Bedford, Leigh, England. is one of the last surviving fragments of Chat Moss, most of which has been drained for agriculture or lost through peat removal. It occupies a 33-hectare site between Astley and the railway. It has been a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) since 1989.[5] Astley Moss is crossed by the Astley Brook and Moss Brook, tributaries to the Glaze Brook that feeds into the River Mersey.[6]

The underlying geology consists of the Permo-Triassic New Red Sandstone in the south, and the Middle Coal Measures of the Manchester CoalfieldPart of the Lancashire Coalfield. Some easily accessible seams were worked on a small scale from the Middle Ages, and extensively from the beginning of the Industrial Revolution until the last quarter of the 20th century. to the north. The upper soils are a mixture of clay and sand, with a subsoil of clay.[4]

Demographics

Census data: Astley

At the 2011 Census the Astley Mosley Common Ward had 11,270 usual residents. The average age of residents was 40.3 years The ward area occupies 1,688.25 hectares giving a population density of 6.7 persons per hectare.[7]

Governance

Astley formed part of the Hundred of West Derby, a judicial division of southwest Lancashire.[8] It was one of six townships or vills that made up the ancient ecclesiastical parish of Leigh. The townships existed before the parish.[4][9] Under the terms of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, the Leigh Poor Law UnionEstablished on 26 January 1837 in accordance with the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, covering the townships of Astley, Atherton, Bedford, Pennington, Tyldesley with Shakerley and Westleigh all in the ancient parish of Leigh, plus Culcheth, Lowton and part of Winwick. was established on 26 January 1837, comprising the whole of the ancient parish and part of Winwick. Workhouses in Pennington, Culcheth, Tyldesley and Lowton were replaced by the workhouse at Atherleigh in the 1850s.[10] In 1894 the civil parishes of Astley, Culcheth, Kenyon and Lowton became part of Leigh Rural District which was dissolved in 1933 and Astley was incorporated into the Tyldesley Urban DistrictTyldesley cum Shakerley Urban District and its successor, Tyldesley Urban District. was from 1894 to 1974 a local government district in Lancashire, England. In 1974 the urban district was abolished and its former area was transfered to the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan in Greater Manchester..[11]

The urban district was abolished in 1974 under the Local Government Act 1972, and Astley became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, a local government district of the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.[12] The Astley electoral ward was formed in 2022 and elects three councillors to the 75-member metropolitan borough council.[13]

Astley was part of the Leigh parliamentary constituency at the 2010 United Kingdom general election.

History

Astley is of Old English derivation, and means either “east (of) Leigh” or ēastlēah the “eastern wood or clearing” , a reference to its position in relation to Leigh. Leigh is derived from lēah, meaning a “wood”, a “clearing” or a “meadow”.[14] The earliest written record of Astley was in documents dated 1210 when it appeared as the Middle English Asteleghe. Other archaic spellings include Asteleye (1292) and Astlegh (14th and 15th centuries).[4] Evidence for the presence of Anglo-Saxons in the sparsely populated, heavily wooded and isolated region is provided by place names incorporating the Old English suffix lēah, such as in Leigh, Tyldesley, Shakerley and Astley.[15]

Manor

Astley emerged during the Early Middle Ages as a township in the parish of Leigh. It was mentioned in documents in 1210, when Hugh of Tyldesley, Lord of the Manors of Tyldesley and Astley, granted land to the religious order of Premonstratensian canons at Cockersand AbbeyFounded as a hermitage before 1184, the remains of which are now a scheduled monument.. In 1212, he was recorded as tenant of Astley Hall, the manor house for both Astley and Tyldesley, located just inside the Tyldesley township. After his death, his son Henry inherited the manors. He was succeeded by his son, another Henry, who, when he died in 1301, divided the lands between three of his six sons. It is from this division that the manors of Astley and Tyldesley were separated. Tyldesleys lived at the Astley manor house until April 1353 when Richard Radcliff bought it for 100 marks.[16] The Radcliffs remained there until 1561 when William Radcliff died childless and the land passed to his half-sister Anne, who married Gilbert Gerard.[17]

In 1606 Adam Mort bought the manor house and land in Astley.[18] He was a wealthy man who built the first Astley ChapelParish church in Astley, Greater Manchester, built in 1968 after its predecessor was destroyed by arson. as a chapel of easeChurch subordinate to a parish church serving an area known as a chapelry, for the convenience of those parishioners who would find it difficult to attend services at the parish church. for the parish church in LeighAncient parish church that served six townships.. The chapel was consecrated in 1631, the year that he died. He built a grammar school that stood for over 200 years until 1833, when it was demolished and rebuilt. Adam Mort’s grandson, also Adam, rebuilt Damhouse in 1650 and his initials are carved in the plaque over the front door.[19] The stone and timber structure was named from the stream which was dammed to supply water to a water wheel powering a corn mill near the house. It is possible the hall was once surrounded by a moat.[16][20]

Adam Mort’s descendants continued to support the chapel and school and remained at Damhouse until 1734 when it was bought by Thomas Sutton.[21] After Sutton’s death in 1752 the house was inherited by Thomas Froggatt of Bakewell who contributed to rebuilding the chapel in 1760. Froggatt’s descendants owned Damhouse until 1800 when it was leased to tenants, one of whom was George Ormerod, owner of the Banks Estate in Tyldesley.[22] In 1839 the house became the property of Captain Adam Durie of Craig Lascar by marriage to Sarah Froggatt.[23] Damhouse was dilapidated when the Duries moved in. Captain Durie gave land to build a school on Church Road. After his death in 1843 his widow, Sarah, married Colonel Malcolm Nugent Ross. The Ross’s Arms public house at Higher Green was named in his honour.[24] The Durie’s daughter Katharine, who married first, Henry Davenport and second Sir Edward Robert Weatherall, became lady of the manor after her mother’s death but the family was in financial difficulties and the house and estate sold in November 1889.[25]

The Leigh Hospital Board bought Damhouse in 1893 for use as a sanatorium dealing with cases of diphtheria, scarlet fever and, in 1947, poliomyelitis. Two bombs fell close to the hospital during the Second World War. It became a general hospital in 1948 dealing with chronically ill and geriatric patients and closed in 1994.[6]

Morleys Hall

Morleys Hall

Morleys Hall, a moated hall converted into two houses on the edge of Astley Moss in Astley, Greater Manchester, England, was largely rebuilt in the 19th century on the site of a medieval timber house. lies on part of the lands donated to Cockersand Abbey by Hugh Tyldesley in 1210. It was owned by the Morleys until 1431, then subsequently by the Leylands. In 1540 it was described as being largely built of timber on stone foundations and surrounded by a moat.[26] IThe hall was rebuilt in 1804, but parts of it survive.[27] Edward Tyldesley of Wardley Hall married Anne Leyland and inherited Morleys in 1564.[28] Their granddaughter, Elizabeth Tyldesley

Elizabeth Tyldesley (1585–1654) was a 17th-century abbess at the Poor Clare Convent at Gravelines. , became abbess of the Convent of Poor Clares at GravelinesConvent in the Spanish Netherlands (now in northern France), founded in 1607 by Mary Ward, a community of English nuns of the Order of St Clare. Commonly called the Poor Clares. in the Spanish Netherlands.[29] The Tyldesleys allowed the martyr, Ambrose Barlow

English Benedictine monk, venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church. to offer secret masses at Morleys where he was eventually arrested.[30] Sir Thomas Tyldesley

Supporter of Charles I and a Royalist commander during the English Civil War. was the most famous of this line of the family, having been a Cavalier commander and supporter of Charles II during the English Civil War. He died in the Battle of Wigan Lane.[31] The hall passed through the Legh and Wilkinson families until it was sold to Tyldesley Urban District CouncilTyldesley cum Shakerley Urban District and its successor, Tyldesley Urban District. was from 1894 to 1974 a local government district in Lancashire, England. In 1974 the urban district was abolished and its former area was transfered to the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan in Greater Manchester. and the land used for a sewage works. The hall is a private residence.[4]

Industrial Revolution

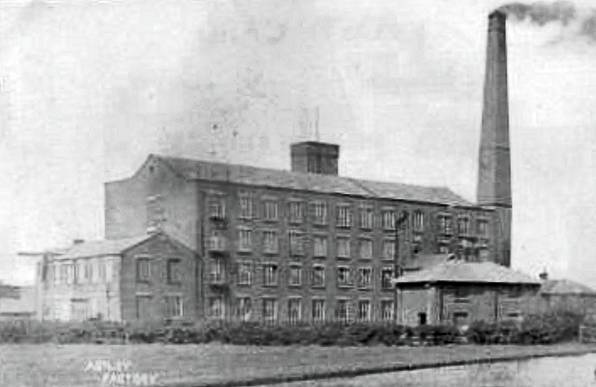

Astley became more industrialised during the early 19th century, but not so much as neighbouring Leigh, Tyldesley and Boothstown. A factory was built by James and Robert Arrowsmith on Peel Lane at Astley Green, near the Bridgewater Canal in 1833. Until then, agriculture and cottage spinning and weaving had been the main economic activities.[32] Fustians, muslins and, after 1827, silkLeigh’s silk industry grew after 1827 in and around the area of the old parish when silk was woven on domestic hand looms and later in weaving sheds using silk yarn supplied from Macclesfield by agents from Manchester. , were woven in the area. Handloom weaving declined after the cotton factory was built. Arrowsmith’s factory lasted until 1955, when mining subsidence damaged its foundations and it was demolished, ending Astley’s link with the textile industry.[23]

Astley on the edge of the Lancashire CoalfieldThe Lancashire and Cheshire Coalfield in North West England was one of the most important British coalfields. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period more than 300 million years ago. had several coal mines within its boundaries.[33] On a map of 1768, a lane leading to Nook and Gin Pit Collieries was called the Coal Road and later North Coal Pit Lane. Gin Pit’s name alludes a method of coal mining, raising coal using a horse ginHorse-driven engine used in lead and shallow coal mines.. An early colliery at Cross Hillock was abandoned in 1886 because of flooding.[34] Samuel Jackson developed the mines that became Astley and Tyldesley CollieriesColliery company formed in 1900, became part of Manchester Collieries in 1929, and some of its collieries were nationalised in 1947. between Astley and Tyldesley. Peat works were opened close to Astley railway station by the Astley Peat Moss Litter Company Limited in 1888.[6]

On 7 May 1908 the Pilkington Colliery CompanyCoal mining company that operated on the south side of the Irwell Valley on the Lancashire Coalfields. started sinking No 1 Shaft of Astley Green Colliery near the Bridgewater Canal.[35] The colliery closed in 1970. It’s headframe still stands and the site is occupied by the Lancashire Mining Museum.

Transport

By 1795, the Bridgewater Canal from Worsley to Manchester had proved an economic success, prompting the Duke of Bridgewater to seek powers to extend its route to Leigh via Astley. The plans were approved, despite opposition from the local population. Canal traffic brought trade to Astley Green where the Hope and Anchor Inn (now the Boathouse) was built with stabling for horses that pulled the barges.[36] The original canal bridge that connected Lower and Higher Green lasted until 1904, when it was replaced. The second bridge was replaced in 1920 by an iron bridge, which could be raised to counter the effects of mining subsidence.[37] A boatyard was established by Lingard’s Bridge.[38]

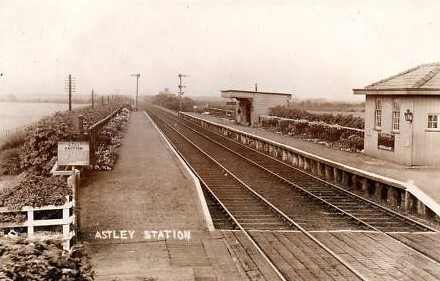

The Liverpool and Manchester Railway of 1830 crosses Astley Moss. It was built on a raft of branches and cotton bales to prevent the track sinking into Chat Moss. The early engines reached speeds of 25 mph and the first passengers told the driver where they wished to alight until Astley railway station was built in the mid-1840s.[39] The railway was distant from the village and early travellers came on horseback or in carriages.[36]

A tramway ran to a wharf on the canal at Marsland Green and a mineral railway linked Gin Pit Colliery to the Tyldesley Loopline at Jackson’s sidings and Bedford Colliery and Speakman’s Sidings.[40]

Religion

Adam Mort built the first Astley Chapel which was consecrated 3 August 1631.[41] When it was rebuilt in 1760, Thomas Froggatt of Damhouse contributed towards the cost.[42] The chapel had a small chancel and its embattled western tower contained a single bell.[4] It was dedicated to Saint Stephen and was destroyed by arson on 18 June 1961. It was too severely damaged to restore and the present church was built on a nearby site.

St Ambrose Church and school in the village bear his name.[43] The St Ambrose Barlow parish was formed in 1965 and the church was built in 1981.Two Methodist churches were built in Astley but one in Lower Green closed in 2009. Astley Unitarian Chapel was demolished and the site built on. Gin Pit School doubled as a chapel for Wesleyan Methodists.

Education

Adam Mort established a grammar school near his chapel in 1631 that was used until 1833. Children from poor families were admitted free and those who could afford to pay covered the costs.[41] Mort’s School closed in 1894.[44] In 1832 children were taught in a barn at the vicarage, the curate, Alfred Hewlett, improved it and the chapel was used as a classroom. A national school built by subscription on land donated by Captain Durie of Damhouse opened in November 1841.[45] Meanleys Infant School was opened at Gin Pit in 1904 to serve the mining community that had grown up there.[2] Other schools were built at Ellesmere Street and Marsland Green.[42]