Tyldesley a former industrial town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan in Greater Manchester takes its name from a Saxon settler. The old township contained ShakerleySuburb of Tyldesley in Greater Manchester, anciently a hamlet in the northwest of the township., Mosley CommonSuburb of Tyldesley in the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, in Greater Manchester. and New ManchesterFormerly isolated mining community at the extreme eastern end of the Tyldesley township..[1] It is 7.7 miles (12.4 km) southeast of Wigan and 8.9 miles (14.3 km) northwest of Manchester. The remains of a Roman road passing through the township on its ancient course between Coccium (Wigan) and Mamucium (Manchester) were evident during the 19th century. Following the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain, Tyldesley was part of the manor of Warrington until the Norman conquest of England, when the settlement constituted the township of Tyldesley-with-Shakerley in the ancient parish of Leigh and the historic county of Lancashire. Its own parish church was consecrated in 1825.

The factory system and textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution, triggered population growth and urbanisation such that by the early 20th century the newly emerged mill town was described as “eminently characteristic of an industrial district whose natural features have been almost entirely swept away to give place to factories, iron foundries, and collieries[2]”. Industrial activity declined in the late 20th century, and land reclamation and post-war residential developments have altered the landscape and encouraged economic activity.

The railway arrived in 1864 but closed in 1969 and nearly fifty years later a guided busway was built on the former trackbed between Leigh and Ellenbrook with four stops in the town.

Geography

Tyldesley is situated at the edge of the Lancashire Plain, north of Chat MossLarge area of peat bog that makes up 30 per cent of the City of Salford, in Greater Manchester, England. The banks of Tyldesley are where the foothills of the Pennines begin. The land rises from about 100 feet (30 m) at the foot of the banks to 250 feet (76 m) at the highest point. The banks, a sandstone escarpment with the scarp slope facing south and the gentler dip to the north, are about one and a half miles (2.4 km) long. The main road through Tyldesley is the A577 which runs on the high ground along the ridge on which the town centre is situated. Red brick terraced houses branching off the main street run down the escarpment slope giving a the town a distinctive character. The Jig or Jig brow[a]Jig is an inclined plane in a coal pit where coal trucks were hauled up a sloping tramroad and brow in south Lancashire (pronounced brew) means a slope on a hillside.[3] were cobbled streets of terraced houses off Manchester Road that ran down the steep slope towards the railway, most have been demolished.

At 53°30′59″N 2°28′0″W (53.5166°, −2.4668°), and 170 miles northwest of central London, Tyldesley is at the eastern end of the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, 7.7 miles (12.4 km) east-southeast of Wigan and 8. miles (13 km) west-northwest of Manchester. The township of Tyldesley and Shakerley covers 2490 acres (1,008 ha). The underlying rocks are the coal measures of the Lancashire CoalfieldThe Lancashire and Cheshire Coalfield in North West England was one of the most important British coalfields. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period more than 300 million years ago. covered with boulder clay. Streams drain the area including the Shakerley and Hindsford Brooks, which flow towards the Glaze Brook, a tributary of the River Mersey.[2]

Demographics

Census data: Tyldesley

At the 2011 Census, the Tyldesley built-up area had a population of 16,142, with a median age of 38.5 years. The built-up area occupies 343 hectares (848 acres), giving a population density of 47.1 persons per hectare.[4]

Governance

Historically in the West Derby Hundred in southwest Lancashire, Tyldesley cum Shakerley was one of six townships Division of an ecclesiastical parish that had civil functions. or vills that made up and predated the ancient parishAncient or ancient ecclesiastical parishes encompassed groups of villages and hamlets and their adjacent lands, over which a clergyman had jurisdiction. of Leigh.[5] Under the terms of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, the township joined the Leigh Poor Law UnionEstablished in 1837, covering townships in the ancient parish of Leigh, plus Culcheth, Lowton and part of Winwick. in 1837. A workhouse in Tyldesley was replaced by the workhouse at Atherleigh in the 1850s.[6]

In 1863 the Local Government Act 1858 was adopted and the township was constituted a civil parishSmallest administrative unit in England. in 1866.[7] The first local board was formed in 1863.[8] The local board offices were in Lower Elliot Street where it had a fire station and depot.[9] Under the Public Health Act 1875 the local board gained additional powers as an urban sanitary district and under the Local Government Act 1894 Tyldesley-with-ShakerleyTyldesley cum Shakerley Urban District and its successor, Tyldesley Urban District. was from 1894 to 1974 a local government district in Lancashire, England. In 1974 the urban district was abolished and its former area was transfered to the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan in Greater Manchester. became an urban districtAdministrative areas that had district councils and shared local government responsibilities with a county council. with an elected council. Tyldesley Town Hall, originally the Liberal Club, was bought by the council as its headquarters in 1924.[10]

In 1933, Lancashire County Council reorganised districts with reference to the Local Government Act 1929. A new Tyldesley Urban District was formed by amalgamating Tyldesley with Shakerley Urban District and the civil parish of Astley from the abolished Leigh Rural District.[11]

The urban district was abolished in 1974 under the Local Government Act 1972, when the area became part of the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan in Greater Manchester. Tyldesley and Mosley Common is an electoral ward of Wigan Council electing three councillors to the 75-member metropolitan borough council, Wigan’s local authority.[12]

Tyldesley is in the Leigh parliamentary constituency which was created in the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885 when the South West Lancashire constituency was divided into eight single member seats. Caleb Wright was elected as the first Liberal Member of Parliament for the new constituency of Leigh in 1885.[10]

History

Tyldesley, “Tilwald’s clearing”, is derived from the Old English personal name Tīlwald and leăh a “wood, clearing”, suggesting what is now open land was once covered with forest.[13] The name was recorded as Tildesleiha in 1210 and as Tildeslei, Tildeslege, Tildeslegh and Tildesley.[2] The town’s situation on the banks gave the town its early name of Tildsley Banks. In local pronunciation “Banks” was corrupted to “Bongs”. The old name for Mosley Common was the “Hurst” or “Tyldesleyhurst”, the suffix hyrst means a wooded hill in Old English.[14]

Earliest history

A Roman road that served camps at Coccium[b]Wigan and Mamucium[c]Manchester passed through the area. It ran from Keeper Delph crossing Mort Lane north west of Cleworth Hall and south of Shakerley Old Hall. The road continued towards the Valley at Atherton and on towards Gibfield and Wigan.[15] In 1947, two urns containing about 550 Roman bronze coins, minted between AD 259 and AD 278, were found near the old Tyldesley–Worsley border[16] The coins are in the British Museum.[17]

After the end of Roman rule in Britain and into the history of Anglo-Saxon England, nothing was written about Tyldesley. Evidence for the presence of Saxons is provided by place names incorporating the Old English suffix leah, such as Tyldesley,[13] Shakerley,[18] and Astley.[19]

Manor houses

Astley HallGrade II* listed building in Tyldesley but considered to be in Astley, Greater Manchester, England. It has served as a manor house, sanatorium, and, since restoration in 2000, houses offices, a clinic and tearooms. was Tyldesley’s manor house which, in 1212 was home to Hugh Tyldesley, Lord of the Manors of Astley and Tyldesley. It is just inside the Tyldesley boundary but has been associated with Astley since the death of Henry Tyldesley in 1301 when the manor was divided among three sons. The Tyldesleys had a “reputation for lawlessness” and “had frequent disputes with their neighbours”.[20] One exception was Hugh Tyldesley, Hugh the Pious,[21] who endowed Cockersand AbbeyFounded as a hermitage before 1184, the remains of which are now a scheduled monument. with land in Shakerley before his death in 1226.[21] The moated New HallScheduled monument in Tyldesley, Greater Manchester, England, which comprises a moat and an island platform on which a modern house has been built. in the Park of Tyldesley, close to the old manor house belonged to Thomas Tyldesley in 1422.[22]

The Garrett was owned by John Tyldesley in 1505. The timber-framed Garrett HallFormer manor house and now a Grade II listed farmhouse in Tyldesley, Greater Manchester, England. remained with the Tyldesleys until 1652 when Lambert Tyldesley died leaving no heir. Its new owners, the Stanleys, leased it to tenant farmers and in 1732 the farmhouse was sold to Thomas Clowes. In 1829 the estate was bought by the Bridgewater Trustees.[23]

Generations of Shakerleys lived in Shakerley Old Hall. They paid rent to Cockersand Abbey and dues of “one pair of white gloves at the feast of Easter” to Adam Tyldesley.[24] Chaddock Hall was home to a family of yeoman farmers.[19] It was recorded as Chaydok, Chaidoke and Chaidok, the last syllable probably meaning “oak”.[21] It was surrounded by a hamlet in the east of the township. The Chaddocks, like the Tyldesleys and Shakerleys, had a reputation for lawlessness.[25] Archers from Chaddock fought at Crécy in 1346 and at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.[26]] In 1360, William Chaddock was described as an archer on foot, “potens de corpore et bonis”.[d]fit for active service in body and equipment A muster roll described Hugh Tyldesley as an archer on horseback and Hugh Chaddock and Richard Tyldesley were foot-archers drawing daily pay for service from 22 July to 21 October 1391.[27]

Cleworth Hall was on higher ground north of the high road.[2] It passed to Nicholas Starkie of Huntroyde who married Anne Parr in 1578. In 1594 it was associated with witchcraft.[28] Two children, John and Anne Starkie, became “possessed of evil spirits”. Edmund HartleyCunning man who is alleged to have practised witchcraft at Cleworth Hall in Lancashire was asked to cure them, which he apparently did before demanding money and Starkie denounced him. Hartley was taken for trial to Lancaster Castle in 1597 where he was tried and found guilty of witchcraft.[29]

Banks Estate

In the early 18th century Tyldesley was a scattered community of cottages and farms around the halls with no church or inn. Thomas Johnson, a Bolton merchant bought the Banks Estate in 1728, land from the Stanleys of Garrett Hall in 1742 and Davenports in the west of the township in 1752. He died in 1764 leaving his estate to his grandson with the same name.[30] Thomas “Squire” Johnson developed the town of Tildsley Banks. His name lives on in Squires Lane and Johnson Street. The last quarter of the 18th century marked the beginning of a building boom and the grid plan of the town centre is from this date.

John Aikin described the area in 1795 in his book “A Description of the Countryside from 30 to 40 Miles around Manchester”:

“The Banks of Tildesley, in the Parish of Leigh, are about one mile and a half in length, and command a most beautiful prospect into seven counties: the springs remarkably clear and most excellently adapted to the purposes of bleaching. The land is rich, but mostly in meadow and pastures, for milk, butter, and the noted Leigh cheese. The estate had, in the year 1780, only two farm houses and eight or nine cottages, but now contains 162 houses, a neat chapel, and 976 inhabitants, who employ 325 looms in the cotton Manufactories…[31]”

Industrial Revolution

Until the Industrial Revolution, Tyldesley was rural, agriculture and cottage spinning and weaving, mainly muslin and fustian,[32] were the chief occupations before 1800. Silk weavingLeigh’s silk industry grew after 1827 in and around the area of the old parish when silk was woven on domestic hand looms and later in weaving sheds using silk yarn supplied from Macclesfield by agents from Manchester. became an important cottage industry after 1827 when silk was brought from Manchester.[33] Thomas Johnson opened the “Little Factory” for carding and spinning cotton in 1772. “The Great Leviathon” powered a steam-driven mill for woollen spinning on Factory Street in 1792. More cotton mills were built close to the Hindsford and Shakerley Brooks which provided water for steam power. Joseph Wilson built Hope Mill in James Street.[34] By 1838 James BurtonJames Burton (1784–1868) was the owner of several cotton mills in Tyldesley and Hindsford in the mid-19th century. owned most of the town’s mills. In 1883 a fire at Burton’s mills caused £15,000 damage and by 1920 his mills had been demolished.[35] Caleb WrightFactory owner and Liberal Member of Parliament, was born in Tyldesley, Lancashire. owned Barnfield MillsFormer complex of six cotton spinning mills, known locally as Caleb Wright's, on either side of Union Street in Tyldesley. which had a workforce of about 800. The last of his mills, Barnfield No 6 on Shuttle Street, was built in 1894 on the site of Resolution Mill which was destroyed by fire in 1891.[34]

In 1429 a dispute arose between the Shakerleys and the Tyldesleys over the theft of “seacoals”.[36] Shakerley Colliery on Shakerley Common was in existence in 1798. Shakerley was a centre for making nails,[37] but was in decline by 1800.

The railway through Tyldesley was completed in 1864 and coal mining became the dominant industry. The town was surrounded by collieries for more than 100 years until the industry declined after the Second World War.[38] Bridgewater CollieriesCoal mining company on the Lancashire Coalfield with headquarters in Walkden near Manchester., Tyldesley Coal CompanyCoal company was formed in 1870 in Tyldesley on the Manchester Coalfield, in the historic county of Lancashire, England. , Ramsden’s Shakerley CollieriesRamsden’s Shakerley Collieries was a coal mining company operating from the mid-19th century in Shakerley, Tyldesley in Lancashire, England. and Astley and Tyldesley CollieriesColliery company formed in 1900, became part of Manchester Collieries in 1929, and some of its collieries were nationalised in 1947. were the local mine owners. Tyldesley Miners Association, established in 1862 at the instigation of Robert IsherwoodRobert Isherwood (1845–1905) was a miner’s agent, local councillor and the first treasurer of the Lancashire and Cheshire Miners’ Federation. ,[39] built the Miner’s Hall in 1893 and the Astley and Tyldesley Miner’s Welfare Club opened at Gin Pit in 1927.

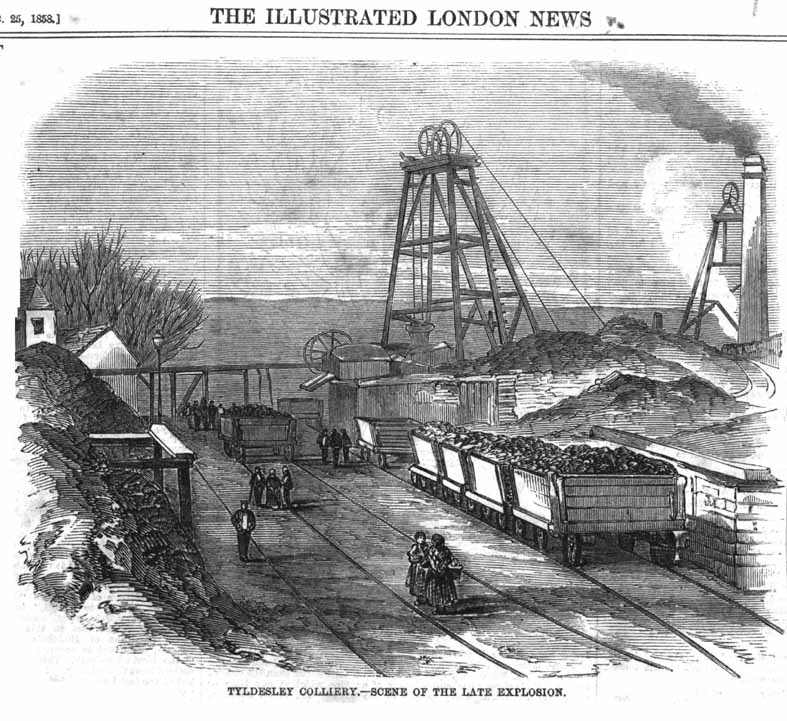

The town’s worst mining disasterMining disasters in Lancashire in which five or more people were killed occurred most frequently in the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s. occurred at Yew Tree CollieryFormer coal mine operating on the Manchester Coalfield after 1845 in Tyldesley, which was then in the historic county of Lancashire, England. in December 1858 when an explosion of firedampDamps is a collective name given to all gases other than air found in coal mines in Great Britain. The chief pollutants are carbon dioxide and methane, known as blackdamp and firedamp respectively. caused by a safety lamp cost twenty-five lives.[40] Another explosion in March 1877 at Great Boys CollieryGreat Boys Colliery in Tyldesley was a coal mine operating on the Manchester Coalfield in the second half of the 19th century in Lancashire, England. cost eight lives[41] and in October 1883, six men died when the cage rope broke at Ramsden’s Nelson Pit in Shakerley.[42] In October 1895 five men including the colliery manager and undermanager died at Ramsden’s Wellington Pit after an explosion of firedamp.[43]

Grundy’s FoundryCompany of heating engineers and ironfounders, started in Tyldesley, Lancashire in 1857. was another important employer. John Grundy invented a warm air heating system that was used in churches and halls. He built a foundry close to the railway in Lower Elliot Street.[44]

Transport

In 1861 the London and North Western Railway revived powers granted to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway to build a railway from Eccles to Wigan through the town.[9] The Earl of Ellesmere cut the first sod at Worsley on 11 September 1861 and the line opened to traffic on 1 September 1864.[45] The railway station was to the east of the junction of the branch to Kenyon Junction on the Liverpool to Manchester Line via Leigh and Pennington.[46] The Tyldesley LooplineRailway line built in 1864 to connect local collieries to the Liverpool–Manchester main line. closed on 3 May 1969 as a result of the Beeching Axe.[47]

In 1900 a Bill authorising South Lancashire Tramways to construct more than 62 miles (100 km) of tramway in southern Lancashire was given Royal Assent.[48] On 25 October 1902 a branch from Atherton to Tyldesley was opened and Tyldesley got its first tram.[49] In August 1931 trams were replaced by trolley buses.[50] Because of Tyldesley’s narrow streets trams and trolley buses followed a one-way system: eastbound via Shuttle Street and westbound via Elliot Street, a system now used by all traffic.

A guided busway was built on the former trackbed but the proposal was not universally popular.[51] After consultations work started on the 4.5-mile (7.2 km) busway from Leigh to Ellenbrook The Leigh-Ellenbrook guided busway is part of the Leigh-Salford-Manchester bus rapid transit scheme in Greater Manchester, England. It provides transport connections between Leigh, Tyldesley and Ellenbrook and onwards to Manchester city centre on local roads. in 2013. It has four stops, Cooling Lane, Astley Street, Hough Lane and Sale Lane and a park and ride site. A pathway for walkers, cyclists and horse riders runs alongside it.[52]

Religion

John Wesley preached in Shakerley four times, between 1748 and 1752, laying the foundations for the township’s first place of worship. Top Chapel was built in the Square in 1789 for the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion. Thomas Johnson, gifted the site and Lady Huntingdon, a supporter of Wesley, supplied money for building materials. The chapel became known as Top Chapel from its geographical location.[53]

Before 1825 Tyldesley had no established church. For ritual baptisms, marriages and burials, the population, had to travel Leigh Parish ChurchAncient parish church that served six townships. or its daughter churches, Astley ChapelParish church in Astley, Greater Manchester, built in 1968 after its predecessor was destroyed by arson. or Atherton ChapelAnglican parish Church in Atherton, Greater Manchester designed by Paley and Austin and completed in 1896 or to Deane or Eccles. St George’s Church

Waterloo church dedicated to St George, completed in 1825 to serve the growing township of Tyldesley cum Shakerley. a chapel of easeChurch subordinate to a parish church serving an area known as a chapelry, for the convenience of those parishioners who would find it difficult to attend services at the parish church. to Leigh, St Mary’s, was built on land donated by Thomas Johnson and consecrated in 1825.[54]

Chapels were built for the Congregational, Primitive Methodist, Wesleyan Methodist, Baptist, Welsh Congregational, Welsh Calvinistic and Independent Methodist connexions.[2] Welsh chapels served the Welsh people who migrated to the town after the opening of the railway in 1864.[55]

Education

George Ormerod gave a site for a national schoolSchools set up by Anglican clergy and their local supporters, initially run by single teachers using the monitorial system. near St George’s Church, it catered for all age groups when it opened in 1827.[56] A day school was opened in the old Wesley Chapel in 1856 and in 1864 was replaced by new school which lasted until 1912. A church school opened in Johnson St in 1872 and closed the 1960s.[57] The British SchoolEstablishments offering education to the children of Nonconformist parents, initially run by a single teacher using the monitorial system. in Upper George Street opened in 1902.[58] The Mission School or Central C of E School in Darlington Street opened in 1892.[59] A board school opened in Lower Elliott Street in 1913 which was used for girls’ secondary education after 1935.[60] Garrett Hall Boys Secondary School opened in 1935.[61]

St George’s Central Primary School, built in the late 1990s. is an amalgamation of the historical St George’s C of E and Central C of E Schools. Other primary schools are Tyldesley Primary School and Garrett Hall Primary. Fred Longworth High School was awarded Arts College status in 1998 St Mary’s Catholic High School in Astley, the only Catholic high school and sixth form in the area.

Notes

| a | Jig is an inclined plane in a coal pit where coal trucks were hauled up a sloping tramroad and brow in south Lancashire (pronounced brew) means a slope on a hillside.[3] |

|---|---|

| b | Wigan |

| c | Manchester |

| d | fit for active service in body and equipment |

References

- pp. 439–445

- p. 6

- pp. 413–421

- p. 682

- p. 128

- p. 129

- p. 139

- p. 689

- p. 355

- p. 404

- p. 7

- p. 132

- p. 17

- p. 5

- p. 5

- pp. 26–27

- p. 28

- p. 6

- p. 10

- p. 20

- p. 21

- p. 27

- p. 47

- p. 92

- pp. 299–300

- p. 53

- p. 10

- p. 107

- p. 114

- p. 31

- p. 103

- p. 126

- p. 48

- p. 220

- p. 116

- p. 32

- p. 71

- p. 63

- p. 362

- p. 7

- p. 21

- p. 74

- p. 100

- p. 109

- p. 8

- p. 112

- p. 134

- p. 149

- p. 144

- p. 151

- p. 156