The Perran Foundry was established between Truro and Falmouth in Cornwall in 1791 by the Fox family of Falmouth and other Quaker partners. It was built to supply steam pumping engines, tin stampsLarge machines for crushing tin and copper ore. and other heavy machinery to tin and copper mines in the nearby Gwennap area and also supplied its products to mines, waterworks and ironworks in many parts of the world. Top quality pig iron was brought from the Neath Abbey blast furnaces in South Wales.

The Williams family of GwennapHamlet and civil parish in West Cornwall. took over the company in 1858. They rebuilt some older buildings and added new ones between 1860 and 1865, but the foundry closed in 1879. After 1890 it was occupied by a milling business until 1985, when it closed for good. The site became run down, but its listed buildings were renovated and incorporated into a residential development after thirty years of dereliction.

Background

In the early 19th century the Perran Foundry was one of the three largest foundries that built steam-pumping engines in the world. The others were Harvey’s of Hayle (1779–1903) and Copperhouse (1820–1869): all three were in west Cornwall.[1] Thomas Newcomen’s steam engine of 1712 provided the impetus to develop deep mining in Cornwall. James Watt’s improved design of 1769 led to a great saving in coal, and the first Watt engines were installed at Cornish mines in 1777.[2] Watt’s patent expired in 1800, and Richard Trevithick then improved designs for a beam pumping engine.[3]

Trevithick built the first high-pressure steam pumping engine in 1801 at the Hayle foundry, and his first mining engine was erected at Wheal Prosper mine in 1811.[3] The Cornish foundries and Neath Abbey Ironworks in South Wales became renowned for building large steam engines for mine pumping throughout Cornwall, Britain and across the world.[3]

History

George Croker Fox, (1728–1781) was a Quaker who founded G.C. Fox and Company, “Consuls, Merchants and Shipping Agents” in Falmouth in 1762. Seven years later he leased wasteland on the south, Mylor, side of the River KennallRiver in south-west Cornwall. from Lord Mount Edgcumbe where Perran Wharf was constructed. This marked the beginning of the industrial development that transformed the Kennall Valley, which was exploited by the Fox family to become one of the principal industrial empires of the early 19th century. The Perran Foundry Company was founded ten years after his death by his sons George Croker Fox II (1752–1807), and Robert Were Fox I (1754–1818).[3]

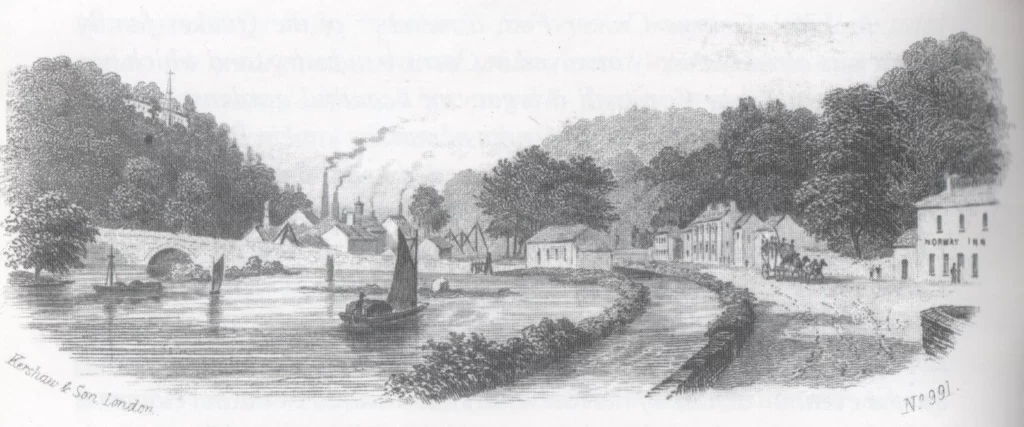

The foundry was established in 1791 on a four-acre (2 ha) site on the Mylor bank of the River Kennall, near where the creek joined a the Carnon RiverHeavily polluted river in West Cornwall, draining the historic mining area of Gwennap.. At this time the Kennall was a navigable tidal inlet of the Fal estuary. It was adjacent to the coach road through PerranarworthalMostly rural parish in West Cornwall., about four miles (6.4 km) south-east of the Gwenapp mines. Fresh water from the Kennall provided power and raw materials were brought into the works by barges. Heavy machinery was taken to deep water at Restronguet for transhipment to sea-going ships.[4] The company also established a trading company to import timber, iron and guano. Copper ore was taken from Perran Wharf to South Wales and coal was brought back as return loads.[5] In 1793 the company acquired a lease on the Neath Abbey Iron Works in South Wales to supply the foundry with pig iron. Up to 1830 the foundry and Neath Abbey each produced parts for the same engine but after that Perran produced increasingly large Cornish engines with cylinders 90 inches (229 cm) in diameter.[6][7]

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Water for power from the Kennall river was provided by water wheels fed by leats, 8 feet (2 m) wide and 2 feet 9 inches deep that could supply up to 1.4 million gallons per hour. The leats followed the river from immediately downstream of the Ponsanooth rail viaduct. Water, supplemented by steam during drier months, powered several wheels on the foundry site including the main hammer wheel in the main forge 18-foot (5 m) diameter); another forge wheel (22-foot (7 m) diameter) in a wheel chamber south of the forge.[9] The iron foundry had three main casting areas each with a cupola-furnace[a]A furnace with a dome leading to a chimney.[10] and stove. The green sand shop was used for simple castings, the dry sand shop for more complex castings, and the loam shop produced very large castings in the floor of the shop itself. The brass foundry and bolt shop produced parts for the engines. Wrought iron was forged in the smiths’ shop. Tilt hammers worked by water wheels were used for heavy forging. Castings and forgings were finished in the engineers’ shop and boring mill.[11]

In 1841 Perran employed 89 adults, 19 youths and 2 children.[12] Charles Fox who had succeeded George Fox in 1825, was the manager. In 1842 His nephew, Barclay Fox took over in 1842. Extensions to the works were made in 1843 and a cast iron, ballustraded footbridge was erected over the Kennall opposite the office. The footbridge was moved when the river was diverted in the 20th century.[7] The Dutch government commissioned giant compound engines to drain the Haarlem Meer from the foundry in partnership with Harveys of Hayle.[13]

The Fox family sold the foundry business to the Williams family in 1858 and it was renamed the Williams Perran Foundry Company and continued trading until 1879. After the sale the works were expanded and the workforce increased. The works then covered six acres (2 ha) and employed 140 people. Five waterwheels fed by the leat system provided power supplemented by steam. Raw materials and products were shipped from Perran Wharf into the Fal.[14]

Most of the Gwennap mines closed in the 1870s causing a slump in trade. Perran was largely dependent on orders from the Gwennap mines, but copper production declined rapidly after 1860 because the mines were becoming worked out and the fall in price of copper because of competition from abroad.[15] Despite orders from abroad Perran closed in March 1879 with the loss of 400 jobs. It caused great distress in the parish.[7] Many skilled men went to work at Falmouth docks, and others moved further afield to the Royal dockyards and Woolwich Arsenal in London.[14]

Closure

The Tuckingmill Foundry Company tried to keep the Perran works open, but in the face of competition from companies in the Midlands, the North and abroad, failed.[14] Harveys of Hayle bought much of the machinery and the stock of iron, and a buyer in Scotland bought one of two iron ships in the yard in 1880. The remaining plant, patterns, wrought and cast-iron, brass, drawings, tracings and other miscellaneous articles were sold in 1881.[7]

The works remained empty for nearly ten years until 1890 when the site was leased by the Edwards brothers. They were millers from the Manor Mill on the opposite side of the turnpike road. They adapted the buildings to mill grain for animal feedstuffs using the old waterwheels. In 1894 they cut a canal and built a quay alongside the new pattern shop of 1865, which was modified to house three pairs of millstones. Barges brought grain to the mill until the 1930s.[16] The Kennall river was again diverted and the iron footbridge was relocated In 1958. Ten years later the mill was modernised and re-equipped and acquired in 1969 by J. Bibby & Sons, who ran down operations and Perran Foundry; the mill closed in 1988 and became derelict.[17]