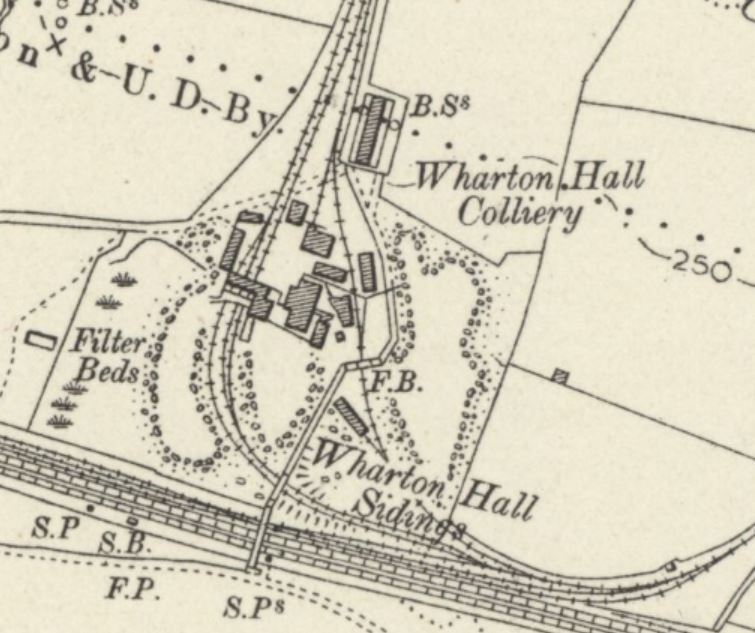

Wharton Hall Colliery 1907.[1]

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

Wharton Hall Colliery was in Little Hulton on the Lancashire CoalfieldThe Lancashire and Cheshire Coalfield in North West England was one of the most important British coalfields. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period more than 300 million years ago. in Lancashire, north-west England. It was sunk on land belonging to the Wharton Hall estate, and its mineral rights extended under 18 Cheshire acres Historical measure of area that was used in the 19th century. of the TyldesleyFormer industrial town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wigan, in Greater Manchester. township.

The colliery was started in 1870 and bought by the Bridgewater Trustees three years later. It had three shafts and was in operation until 1927, although its coal reserves were not exhausted. Its spoil heap was removed in 2000, and the area to the east was opencasted in a major reclamation project.

History

John Gerrard Potter bought the Wharton Hall estate in 1870 and started sinking two shafts in about 1873, but sold the estate to the Bridgewater Trustees in 1879 or 1880.[2] The Bridgewater TrusteesCoal mining company on the Lancashire Coalfield with headquarters in Walkden near Manchester. developed the colliery. Walker Brothers of Wigan installed staging with a galvanised iron roof over the screens, sorting belts, chutes and tub tipplers in 1888/89. A Schiele fan for ventilation was installed. It measured 12 feet 6 inches in diameter and 4 feet wide and was driven by a 20 in x 36 in horizontal engine. Steam for the surface plant was supplied by five Lancashire boilers.[3]

The colliery had three shafts, the 14-foot diameter No. 1 Pit was sunk to 312 yards. No. 2 Pit, at 14 feet 3 inches in diameter, reached the Arley mine at 551 yards in 1903. No. 3 Pit, 11 feet in diameter, was sunk to 461 yards. All had twin-cylinder horizontal winding engines. No. 1 had a 26 inch x 60 inch engine and No. 3 had a 20 inch x 42 inch engine and a 9-foot diameter by 6ft 6in wide rope drum. No. 2’s engine had 30in x 60in cylinder.[3]

In 1923 Wharton Hall, Nos. 1, 2 & 3 Pits had 565 underground and 112 surface workers.[4] After the closure of Wharton Hall in 1927, Brackley Colliery, about three quarters of a mile (1.2 km) to the north, took over its reserves.

When coal winding ceased in December 1927, No. 2 Pit was retained as a pumping station. The shaft’s lattice girder headgear remained in place until 1964.[5] No. 1 Pit was abandoned and the shaft was bricked round at the top. Three boilers were retained to provide steam for the remaining winding engines and the Walker compressor. In 1933-34 the pumping operation and No. 2 winding engine were electrified. The air compressor was moved to Howe Bridge Colliery, the boiler plant was demolished and a boiler was moved to Gin PiColliery that operated on the Lancashire Coalfield from the 1840s in Tyldesley Lancashire, England. t in Tyldesley. No. 3 Pit was retained for periodic inspections by hoppit and tackle or the portable winding engine from Boothstown Mines Rescue StationMines rescue station serving the collieries of the Lancashire and Cheshire Coal Owners on the Lancashire Coalfield, opened in 1933. .[3]

Incidents

During the third week of 1881 Lancashire miners’ strikeBitter and violent Lancashire miners' strike of 1881 that lasted for seven weeks, and ended with no resolution. , miners from Wigan marched through the district to stop strkebreakers from working. At Wharton Hall there was fighting between the strikers and the police that only ended when the strikebreakers were withdrawn from the pit. Many policemen were injured after being hit by lumps of coal. Samuel Findlay, aged 18, died in a baton charge when police reinforcements attempted to disperse the strikers who had marched on the pit to bring out blackleg workers.[6][7]

Cutacre

The colliery’s spoil heap, one of the largest in the country, was not removed until after 2000 when the tip and a 330-acre (134 ha) area around it was opencasted in a complex regeneration scheme. The area was restored and landscaped with provision for employment and a country park with areas of woodland, water and footpaths.[8]