Although witches in the popular imagination are widely believed to have flown through the air on broomsticks, only a rather small number ever confessed to having done so. The first was Guillaume Edelin – a male witch from St. Germain-en-Laye near Paris – who in 1453 admitted to flying on a broom.[1][a]Edelin was a French doctor of theology who repeated the claims of the medieval Canon Episcopi that witchcraft was an illusion, and that witches were unable to fly, until he himself was arrested for witchcraft. Under torture, he confessed that he had flown on a broom, and that he had been commissioned by Satan to preach that witchcraft was an illusion.[2] Far from being a ubiquitous witches’ tool, a broomstick is mentioned in only one account of an English witch-trial.[3]

The power of flight was associated with the application of a special flying ointment to the broomstick before mounting it. According to the Errores Gazariorum, published in about 1450, every witch on his or her initiation was presented with a stick and a jar of the ointment.[4]

Sexualisation

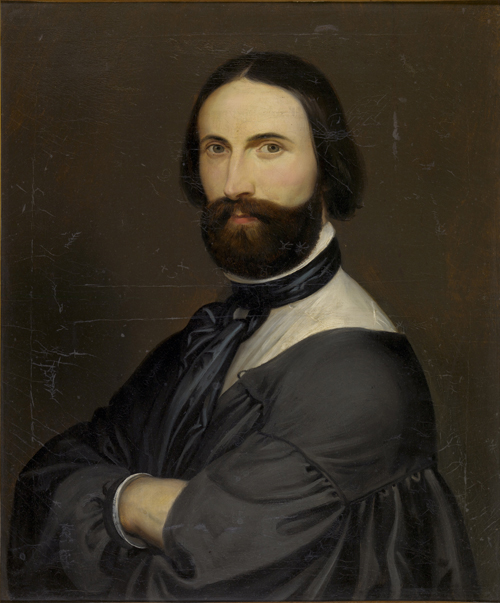

Belgian Romantic painter and sculptor. His output, featuring such macabre scenes as violent suicide and premature burial has persuaded some critics to consider it the work of a madman.

Belgian Romantic painter and sculptor. His output, featuring such macabre scenes as violent suicide and premature burial has persuaded some critics to consider it the work of a madman.Wikimedia Commons

Much of what we know about medieval witches and witchcraft comes from the records left by inquisitors, ecclesiastical judges and confessions from the accused witches themselves, often obtained under torture, so its reliability must always be in doubt. Nevertheless there exists a body of Renaissance art depicting witches riding on a variety of objects including stools, cupboards and various animals as well as broomsticks.[5]

Early accounts of the flying ointment applied to the broomstick, such as that of Johannes Hartlieb in his The Book of All Forbidden Arts, Superstitions, and Sorcery (1475) describe it as being composed of various herbs, some of them undoubtedly psychoactive such as henbane, but by the time of the Malleus Maleficarium, just a few years later, it was said to consist of the residue from the boiled flesh of (preferably) unbaptised children.[6]

The idea that psychoactive ointments may be more readily absorbed if the anointed broomstick is rubbed against the private parts, as is apparently portrayed in Antoine Wiertz’s The Young Sorceress (1857), or inserted into the vagina or rectum, is perhaps part of our modern idea of witches riding broomsticks.[7]

Legal opinion on flying

Most early 17th-century demonologists, including King James I, held that only God could perform miracles, and that he had not given the power to go against the laws of nature to those in league with the Devil. As flying was considered to be against the laws of nature it was not something they believed that witches could do,[8] although in reality Eilmer of Malmesbury Benedictine monk who became the first European aviator when between 1000 and 1010 AD he jumped from the summit of a tower with wings fastened to his hands and feet, gliding for a distance of about 600 ft. had demonstrated the feasibility of heavier-than-air flight more 600 years earlier, the first European to do so. Nevertheless, it is not specifically referred to in any of the Witchcraft Acts

Benedictine monk who became the first European aviator when between 1000 and 1010 AD he jumped from the summit of a tower with wings fastened to his hands and feet, gliding for a distance of about 600 ft. had demonstrated the feasibility of heavier-than-air flight more 600 years earlier, the first European to do so. Nevertheless, it is not specifically referred to in any of the Witchcraft Acts Series of Acts passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland making witchcraft a secular offence punishable by death..

Series of Acts passed by the Parliaments of England and Scotland making witchcraft a secular offence punishable by death..

By the mid-18th century witchcraft had come to be considered an impossible crime by those influential in English society, an attitude embodied in the Witchcraft Act of 1735 Sometimes dated 1736, an Act of Parliament that repealed the statutes concerning witchcraft throughout Great Britain, including Scotland.. It eliminated all punishments for the practice of witchcraft and instead targeted those who fraudulently claimed to have the powers formerly attributed to witches, such as fortune telling and sorcery. But it was not until the end of the century that the specific question of witches flying on broomsticks was thrashed out in an English court, when Lord Mansfield recorded his judgement that:

Sometimes dated 1736, an Act of Parliament that repealed the statutes concerning witchcraft throughout Great Britain, including Scotland.. It eliminated all punishments for the practice of witchcraft and instead targeted those who fraudulently claimed to have the powers formerly attributed to witches, such as fortune telling and sorcery. But it was not until the end of the century that the specific question of witches flying on broomsticks was thrashed out in an English court, when Lord Mansfield recorded his judgement that:

Notes

| a | Edelin was a French doctor of theology who repeated the claims of the medieval Canon Episcopi that witchcraft was an illusion, and that witches were unable to fly, until he himself was arrested for witchcraft. Under torture, he confessed that he had flown on a broom, and that he had been commissioned by Satan to preach that witchcraft was an illusion.[2] |

|---|