Guy Fawkes; or, The Gunpowder Treason, first appeared as a serial in Bentley’s MiscellanyIllustrated monthly magazine published from 1837 until 1868.Illustrated monthly magazine published from 1837 until 1868. from January until November 1840, and was subsequently published as a three-volume set in July 1841, with illustrations by George Cruikshank. The first of William Harrison Ainsworth’s

English historical novelist, at one time considered a rival to Charles Dickens. seven Lancashire novels, the story is based on the Gunpowder PlotAttempt in 1605 to assassinate King James I and re-establish a Catholic monarchy by blowing up the House of Lords. of 1605, an unsuccessful attempt to blow up the House of Lords and introduce a Catholic monarch.

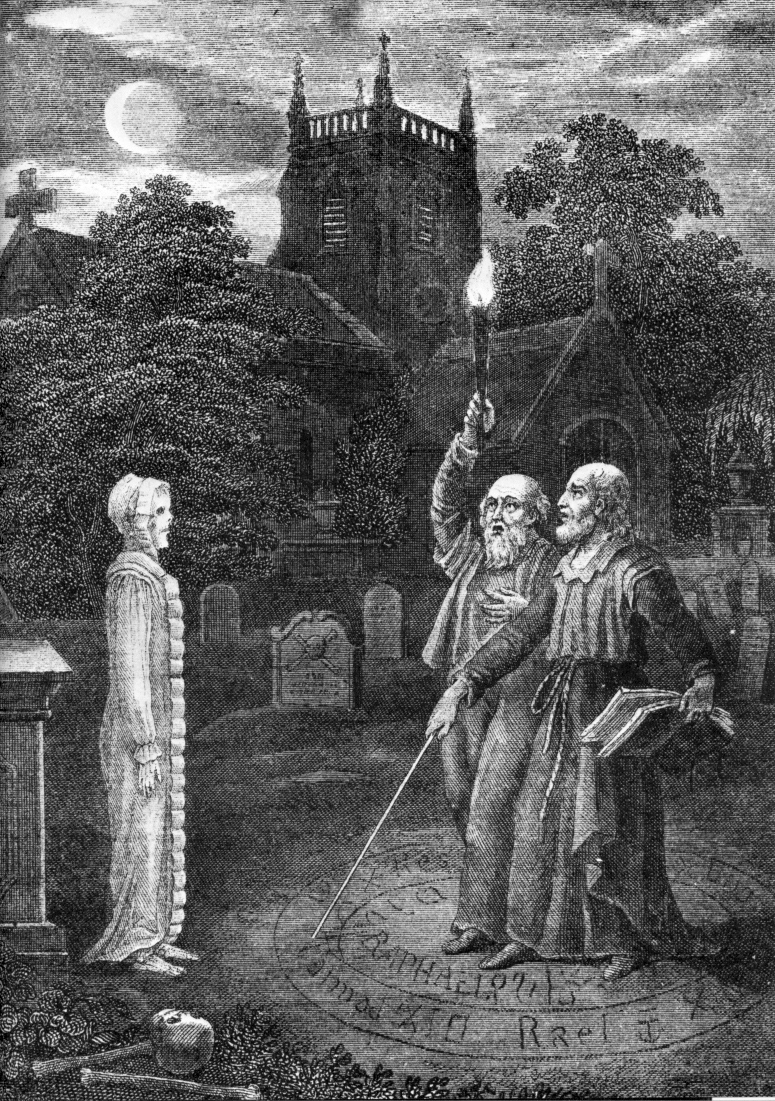

Ainsworth based his novel on historical documents describing the trial and execution of the conspirators, of whom Fawkes was one, but embellished his account. In particular, he invented the character of Viviana Radcliffe, daughter of the prominent Radcliffe family of Ordsall Hall

Large former manor house in the historic parish of Ordsall, Lancashire, England, now part of the City of Salford, in Greater Manchester. , and introduced gothic and supernatural elements such as the ability of the alchemist John Dee to raise the spirits of the dead.

The novel’s popularity marked the beginning of Ainsworth’s 40-year career in historical romances, although it was not universally admired; the American author Edgar Allan Poe described Ainsworth’s style of writing as “turgid pretension”.[1]

Publication history

During 1840 Ainsworth simultaneously wrote The Tower of LondonNovel by the English author William Harrison Ainsworth, first published in 1840, centred on the events following the death of King Edward VI and the subsequent nine-day reign of Lady Jane Grey as Queen of England. and Guy Fawkes, both first published as serials; Guy Fawkes was published in instalments in Bentley’s MiscellanyIllustrated monthly magazine published from 1837 until 1868.Illustrated monthly magazine published from 1837 until 1868. from January until November 1840.[2] Ainsworth serialised the story again in his own publication, Ainsworth’s Magazine, between 1849 and 1850.[3]

The first edition in novel form was published by Richard Bentley, the owner of Bentley’s Miscellany, in July 1841, as a three-volume set illustrated by George Cruikshank;[2] two American editions and a French one were published in the same year. Routledge published three further editions in 1842, 1857 and 1878.[3]

Plot

The story begins in mid-1605, when a plot to blow up parliament and replace the Protestant monarch with a Catholic is being hatched. The first book begins with the execution of Catholic priests in Manchester. During their execution, Elizabeth Orton madly raves before being chased by an officer overseeing the executions. To avoid capture she leaps into the River Irwell, and is pulled out by Humphrey ChethamEnglish merchant responsible for the creation of Chetham's Hospital and Chetham's Library, the oldest public library in the English-speaking world. , a Protestant member of the nobility, and Guy FawkesMember of the group of English Catholics who planned the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605., a Catholic. After her rescue she predicts the execution of both men.

The novel then transitions to Lancashire and the Radcliffe family. William Radcliffe is a supporter of the plot, and his daughter, Viviana Radcliffe, is revealed to be in love with both Chetham and Fawkes. Fawkes travels to John Dee, an alchemist who is able to call forth Orton’s ghost. The spectre repeats its warning, and Fawkes receives a vision from God that the plot will end in disaster. Meanwhile the Radcliffe family is exposed as hiding two priests,[a]Prominent Catholic families protected chaplains and itinerant priests from legal persecution during the late 16th and early 17th centuries by building priest holesSecret hiding places in the homes of prominent Catholics to hide priests from persecution. in their homes.[4] which provokes the destruction of their home by the British Army, following which the conspirators travel to London.

In the second book Fawkes and Viviana Radcliffe marry, and she tries to convince her new husband to abandon the plot, but Fawkes argues that he is bound to follow through with events. The book ends when the conspiracy to blow up parliament on 5 November 1605 fails, and Fawkes is arrested.

The third book deals with the trials of Fawkes and the other plotters, who have been held in the Tower of London. Viviana, who is by then dying, convinces Fawkes to repent, which he eventually he does as she dies, following which he is executed. The book ends with the execution of the last of the plotters, Father GarnetEnglish Jesuit priest executed for his complicity in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605..

Themes

Guy Fawkes deals with British politics and history; the execution of Catholic priests and the plot to destroy parliament, titillated with the injection of gothic elements such as a cave linked to pagan worship and the desolate Chat MossLarge area of peat bog that makes up 30 per cent of the City of Salford, in Greater Manchester, England, a bog near Manchester.[5]

The use of prophecy by necromancy

Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive. distinguishes Ainsworth from earlier authors, who incorporated Catholic superstition in their use of the gothic genre. Ainsworth instead has Christianity and the supernatural as elements of a unified entity, reflecting a view that magic, religion, and science were once different aspects of a single world view; the character John Dee, an alchemist, represents that unifying link.[5]

Ainsworth’s treatment of the women in his story is somewhat at odds with the independent females in his other novels. Vivian is obedient to her father, prepared to die for his cause, but unable to escape from what she knows to be hopeless because of her vows of marriage:

— William Harrison Ainsworth

Critical reception

Guy Fawkes, along with The Tower of London, marked the beginning of Ainsworth’s 40-year career in historical romances.[7] But although popular, the work was not universally admired. In 1841 the American writer Edgar Allan Poe wrote in a review that it was “… positively beneath criticism and beneath contempt”, going on to say that “The design of Mr. Ainsworth has been to fill, for a certain sum of money, a stipulated number of pages”.[8]

It was reported that Ainsworth was paid up to £1,500 for Guy Fawkes, equivalent to about £145,000 as at 2021.[b]Calculated using the retail price index.[9] The Ainsworth biographer S. M. Ellis considered it to be “one of the best historical novels”,[10] but others have been less fulsome. A later biographer, George Worth, argued that “All is well during the first two of the three parts of Guy Fawkes … But in the third section … Ainsworth rather badly lets his audience down.”[11] Yet another, Stephen Carver, stated his view that “Although critics are often scathing of this author, Guy Fawkes Book the Second is a reasonable history lesson”.[12]

Whatever its literary merits, Ainsworth’s novel transformed Fawkes into an “acceptable fictional character”, and he began to feature in children’s books and penny dreadfulsCheap popular serial literature produced during the 19th century, typically a story published in weekly parts, each costing a penny..[13]

See also

- William Harrison Ainsworth bibliography

Works of William Harrison Ainsworth (1805–1882) listed in order of their date of first publication.

Notes

| a | Prominent Catholic families protected chaplains and itinerant priests from legal persecution during the late 16th and early 17th centuries by building priest holesSecret hiding places in the homes of prominent Catholics to hide priests from persecution. in their homes.[4] |

|---|---|

| b | Calculated using the retail price index.[9] |

References

Bibliography

External links

- Full text of Guy Fawkes at Project Gutenberg