Wikimedia Commons

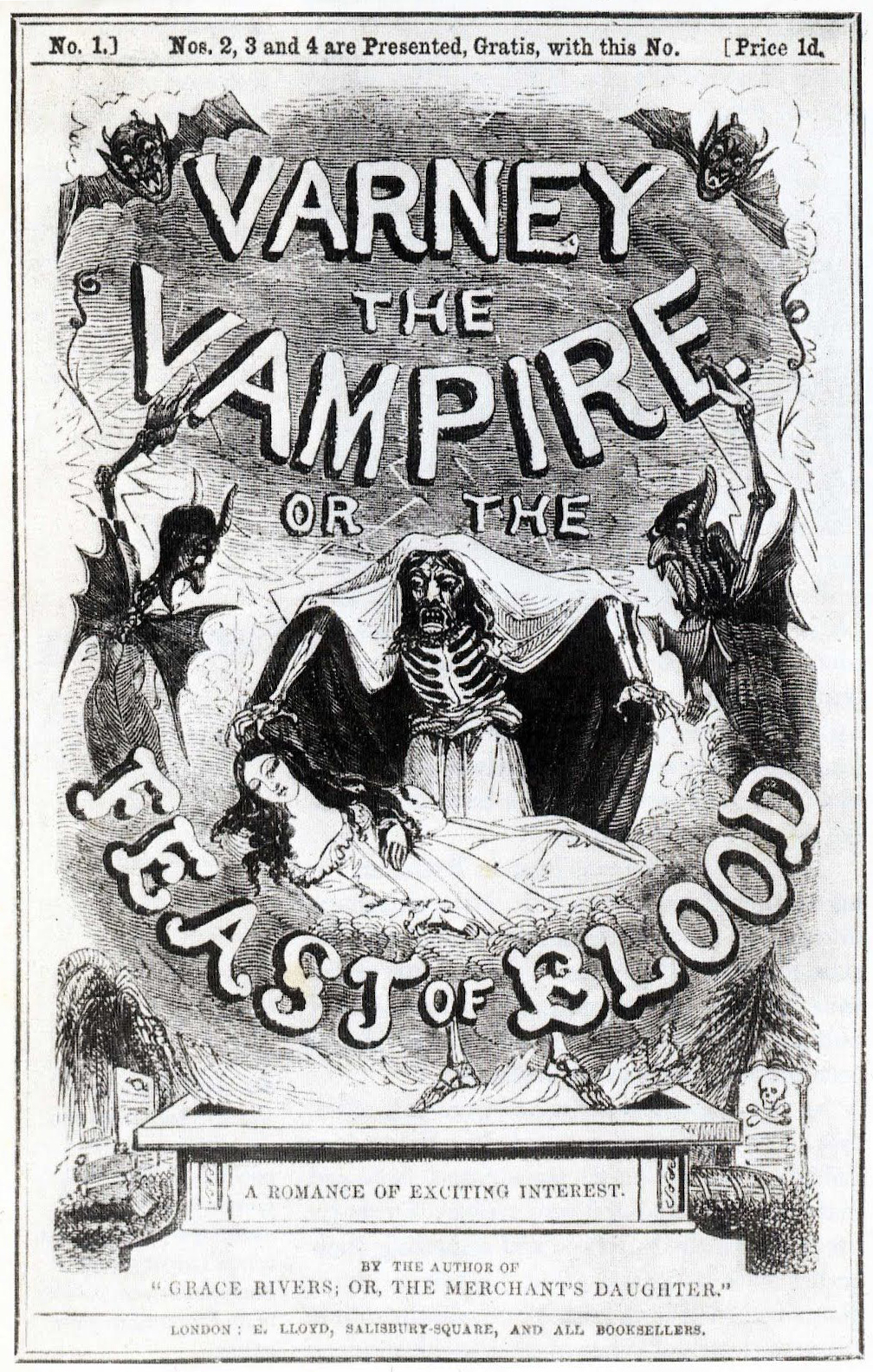

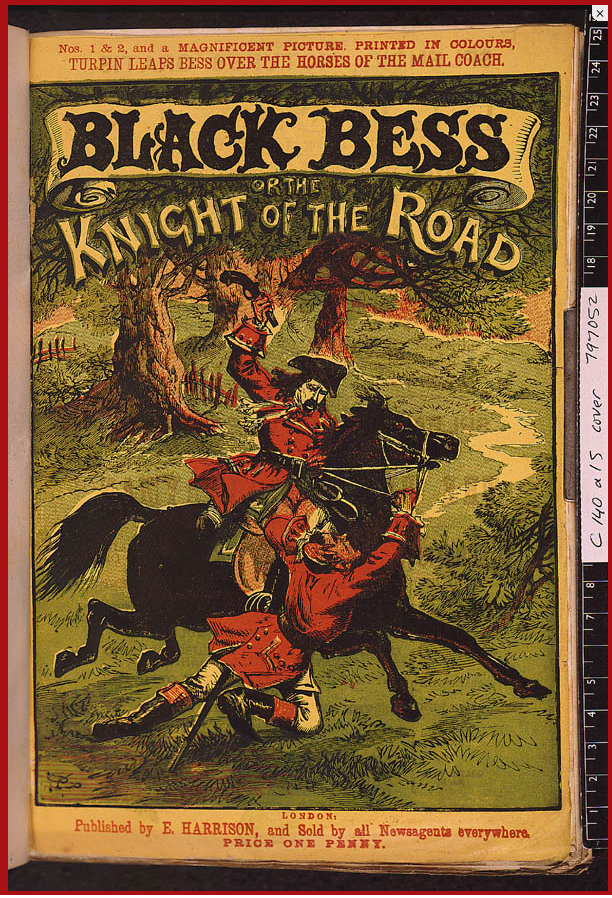

Penny dreadfuls, or penny bloods, were cheap popular serial literature produced during the 19th century in the United Kingdom, “Britain’s first taste of mass-produced popular culture for the young.”[1] The term typically referred to a story published in weekly parts, each costing one penny. The subject matter was usually sensational, focused on the exploits of detectives, criminals, or supernatural entities. First published in the 1830s, penny dreadfuls featured characters such as Sweeney ToddFictional character who first appeared as the villain of the Victorian penny dreadful serial The String of Pearls (1846–1847). Fictional character who first appeared as the villain of the Victorian penny dreadful serial The String of Pearls (1846–1847). , Dick Turpin

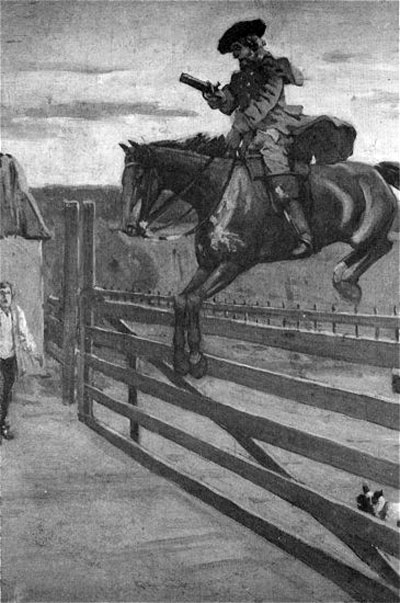

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess.

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess.

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess. and Varney the VampireMain character in a series of penny dreadfuls produced from 1845 until 1847. The stories introduced many of the ideas represented in modern vampire stories, such as Varley's fangs leaving two puncture wounds on the necks of his victims..

Although the term “penny dreadful” was originally used in reference to a specific type of literature circulating in mid-Victorian Britain, it came to encompass a variety of publications that featured cheap sensational fiction, such as story papers and booklet “libraries”. Penny dreadfuls were printed on cheap wood pulp paper and were aimed at young working class men.[2] More than a million boys’ periodicals were sold a week, but the popularity of penny dreadfuls was challenged in the 1890s by the rise of competing literature, especially the half-penny periodicals published by Alfred Harmsworth.[1][3]

Origins

Crime broadsides were commonly sold at public executions in the United Kingdom during the 18th and 19th centuries, often produced by specialist printers. They were typically illustrated by a crude picture of the crime, a portrait of the criminal, or a generic woodcut of a hanging taking place. There would be a written account of the crime and of the trial and often the criminal’s confession of guilt. A doggerelClumsy and awkward verse often employed for comic effect. verse warning others not to follow the executed person’s example, to avoid their fate, was another common feature.[4]

Victorian-era Britain experienced social changes that resulted in increased literacy rates. With the rise of capitalism and industrialisation, people began to spend more money on entertainment, contributing to the popularisation of the novel. Improvements in printing resulted in newspapers such as Joseph Addison’s The Spectator and Richard Steele’s The Tatler, and England’s more fully recognising the singular concept of reading as a form of leisure; it was, of itself, a new industry. Other significant changes include the invention of the locomotive and the development of a railway network,[a]The first public railway, Stockton and Darlington Railway, opened in 1825. all of which created a market for cheap popular literature and the means to circulate it widely. The first penny serials were published in the 1830s to meet this demand.[5] Between 1830 and 1850 there were up to 100 publishers of penny fiction, in addition to many magazines which embraced the genre.[6] The serials were priced to be affordable to working-class readers, being considerably cheaper than the serialised novels of authors such as Charles Dickens, which cost a shilling [twelve pennies] per part.[7]

Subject matter

Wikimedia Commons

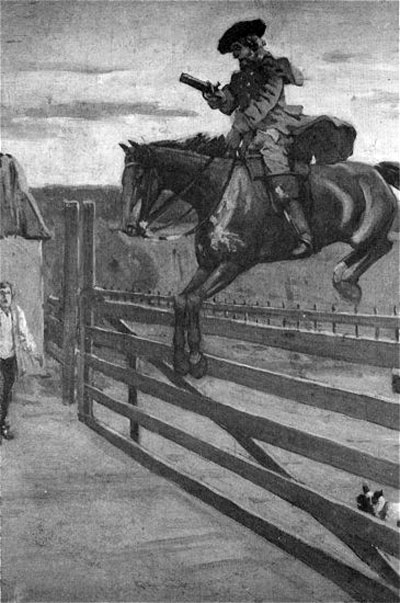

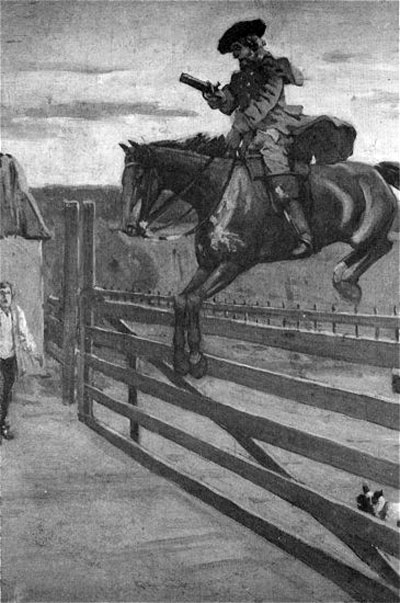

The stories themselves were reprints, or sometimes rewrites, of the earliest Gothic thrillers such as The Castle of Otranto or The Monk, as well as new stories about famous criminals. The first ever penny blood, published in 1836, was Lives of the Most Notorious Highwaymen, Footpads, &c. The story continued over sixty issues, each eight pages of tightly packed text with one half-page illustration.[6] Highwaymen were popular heroes; Black Bess or the Knight of the Road, outlining the largely imaginary exploits of real-life English highwayman Dick Turpin

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess.

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess.

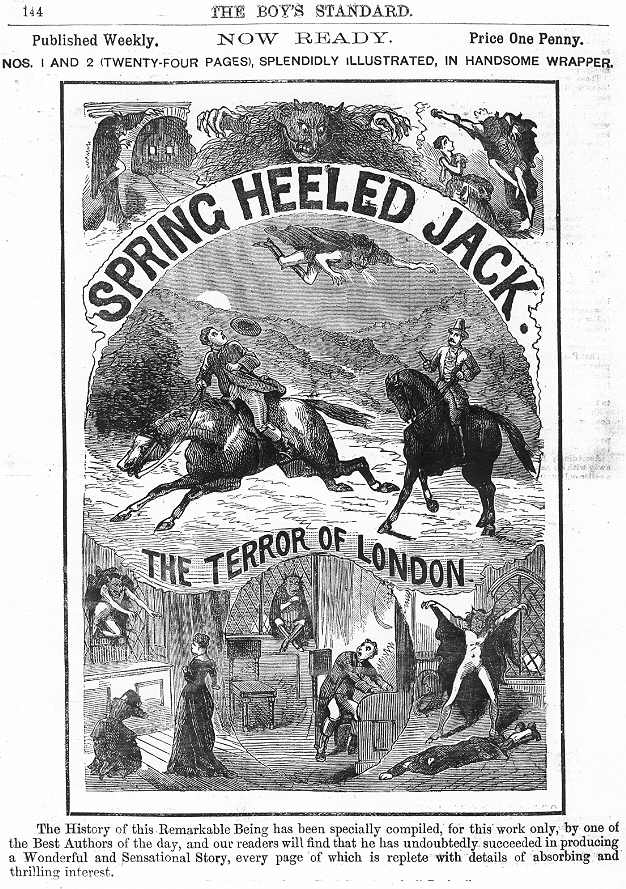

English highwayman whose exploits were romanticised following his execution in York for horse theft. In the popular imagination he is best remembered for a fictional 200-mile ride from London to York on his horse Black Bess., continued for 254 episodes and was more than 2,000 pages long; Turpin was not executed until page 2,207. Some lurid stories purported to be based on fact, but Spring-Heeled Jack was what we would now call an urban myth. The first “sighting” of him was in 1837, when he was described as having a terrifying and frightful appearance, with diabolical physiognomy, clawed hands and eyes that “resembled red balls of fire”. He was mainly sighted in London, but popped up elsewhere, and seems to have been a source of frightened fascination for several decades. At the height of Spring-Heeled Jack hysteria, several women reported being attacked by a clawed monster of a man breathing blue flames; the last reported sighting was in Liverpool in 1904. Other serials were thinly disguised plagiarisms of popular contemporary literature. The publisher Edward Lloyd, for instance, published a number of penny serials derived from the works of Charles Dickens entitled Oliver Twiss, Nickelas Nicklebery, and Martin Guzzlewit.[5]

The illustration which featured at the start of each issue was an integral part of the Dreadfuls’ appeal, often acting as a teaser for future instalments. As one reader said, “You see’s an engraving of a man hung up, burning over a fire, and some [would] go mad if they couldn’t learn … all about him.” Little wonder that one publisher’s rallying cry to his illustrators was “more blood – much more blood!”[6]

Working class boys who could not afford a penny a week often formed clubs that would share the cost, passing the flimsy booklets from reader to reader. Other enterprising youngsters would collect a number of consecutive parts, then rent the volume out to friends. In 1866, Boys of England was introduced as a new type of publication, an eight-page magazine that featured serial stories as well as articles and shorts of interest.[8]

The penny dreadfuls were influential since they were, in the words of one commentator, “the most alluring and low-priced form of escapist reading available to ordinary youth, until the advent in the early 1890s of future newspaper magnate Alfred Harmsworth’s price-cutting ‘halfpenny dreadfuller'”.[9] In reality, the serial novels were overdramatic and sensational, but generally harmless. If anything, the penny dreadfuls, although obviously not the most enlightening or inspiring of literary selections, resulted in increasingly literate youth in the Industrial period. The wide circulation of this sensationalist literature, however, contributed to an ever-greater fear of crime in mid-Victorian Britain.[10]

Decline

The popularity of penny dreadfuls was challenged in the 1890s by the rise of competing literature. Leading the challenge were popular periodicals published by Alfred Harmsworth. Priced at one half-penny, Harmsworth’s story papers were cheaper and, at least initially, were more respectable than the competition. Harmsworth claimed to be motivated by a wish to challenge the pernicious influence of penny dreadfuls. According to an editorial in the first number of The Half-penny Marvel in 1893:

The Half-penny Marvel was soon followed by a number of other Harmsworth half-penny periodicals, such as The Union Jack and Pluck. At first the stories were high-minded moral tales, reportedly based on true experiences, but it was not long before these papers started using the same kind of material as the publications they competed against. A. A. Milne, the author of Winnie the Pooh, once said, “Harmsworth killed the penny dreadful by the simple process of producing the ‘ha’penny dreadfuller'”.[11]

The penny dreadfuls were also challenged by book series such as The Penny Library of Famous Books launched in 1896 by George Newnes which he characterized as “penny delightfuls” intended to counter the pernicious effects of the penny dreadfuls.[12]

Legacy

Two popular characters to come out of the penny dreadfuls were Jack Harkaway, introduced in the Boys of England in 1871, and Sexton Blake, who began in the Half-penny Marvel in 1893.[13] The fictional Sweeney ToddFictional character who first appeared as the villain of the Victorian penny dreadful serial The String of Pearls (1846–1847). Fictional character who first appeared as the villain of the Victorian penny dreadful serial The String of Pearls (1846–1847). , the subject of a successful musical by Stephen Sondheim and a feature film by Tim Burton, also first appeared in an 1846/1847 penny dreadful titled The String of Pearls: A Romance.[14]

Over time, the penny dreadfuls evolved into the British comic magazines. Owing to their cheap production, their perceived lack of value, and such hazards as war-time paper drives, the penny dreadfuls, particularly the earliest ones, are fairly rare today.[15]