Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies, published from 1757 to 1795, was an annual directory of prostitutes then working in Georgian London. A small pocketbook, it was printed and published in Covent Garden, and sold for two shillings and sixpence. A contemporary report of 1791 estimates its circulation at about 8000 copies annually.

Each edition contains entries describing the physical appearance and sexual specialities of about 120–190 prostitutes who worked in and around Covent Garden. Through their erotic prose, the list’s entries review some of these women in lurid detail. While most compliment their subjects, some are critical of bad habits, and a few women are even treated as pariahs, perhaps having fallen out of favour with the list’s authors, who are never revealed.

Samuel Derrick is the man usually credited for the design of Harris’s List, possibly having been inspired by the activities of a Covent Garden pimp, Jack Harris. A Grub StreetOnce a London street famous for its low-end publishers and hack writers, Grub Street has become a pejorative term for impoverished writers and works of low literary value. hack, Derrick may have written the lists from 1757 until his death in 1769; thereafter, the annual’s authors are unknown. Throughout its print run it was published pseudonymously by H. Ranger, although from the late 1780s it was printed by three men: John and James Roach, and John Aitkin.

As the public’s opinion began to turn against London’s sex trade, and with reformers petitioning the authorities to take action, those involved in the release of Harris’s List were in 1795 fined and imprisoned. That year’s edition was the last to be published; by then its content was cruder, lacking the originality of earlier editions. Modern writers tend to view Harris’s List as erotica; in the words of one author, it was designed for “solitary sexual enjoyment”.[1]

Introduction

Wikimedia Commons

The earliest printed editions of Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies appeared after Christmas 1756. Published by “H. Ranger”, the annual was advertised on the front pages of newspapers, and sold in Covent Garden and at booksellers’ stalls. Each edition comprises an attractive pocketbook, “beautifully packaged … in the modish style of the twelves”.[2][a]By this the author means duodecimo-sized pages. They usually contained no more than 150 pages of relatively thin paper, on which are printed the details of between 120 and 190 prostitutes then working in Covent Garden. Priced in 1788 at two shillings and sixpence, Harris’s List was affordable for the middle classes but expensive for a working class man.[3][4]

It was not the first directory of prostitutes to be circulated in London. The Wandering Whore ran for five issues between 1660 and 1661, in the early (and newly liberal) years of the Restoration. Allegedly an exposé of the capital’s sex trade and usually attributed to John Garfield, it lists streets in which prostitutes might have been found, and the locations of brothels in areas including Fleet Lane, Long Acre and Lincoln’s Inn Fields.[5] The Wandering Whore incorporates dialogue between “Magdalena, a Crafty Whore, Julietta, an Exquisite Whore, Francion, a Lascivious Gallant, and Gusman, a Pimping Hector”,[6][7] with the caveat that it was disseminated only so that law-abiding folk might avoid such people. Another publication was A Catalogue of Jilts, Cracks & Prostitutes, Nightwalkers, Whores, She-friends, Kind Women and other of the Linnen-lifting Tribe, printed in 1691. This catalogues the physical attributes of 21 women who could be found about St Bartholomew-the-Great Church during Bartholomew Fair, in Smithfield. Mary Holland was apparently “tall, graceful and comely, shy of her favours”, but could be mollified “at a cost of £20”. Her sister Elizabeth was less expensive, being “indifferent to Money but a Supper and Two Guineas will tempt her”.[8]

Content

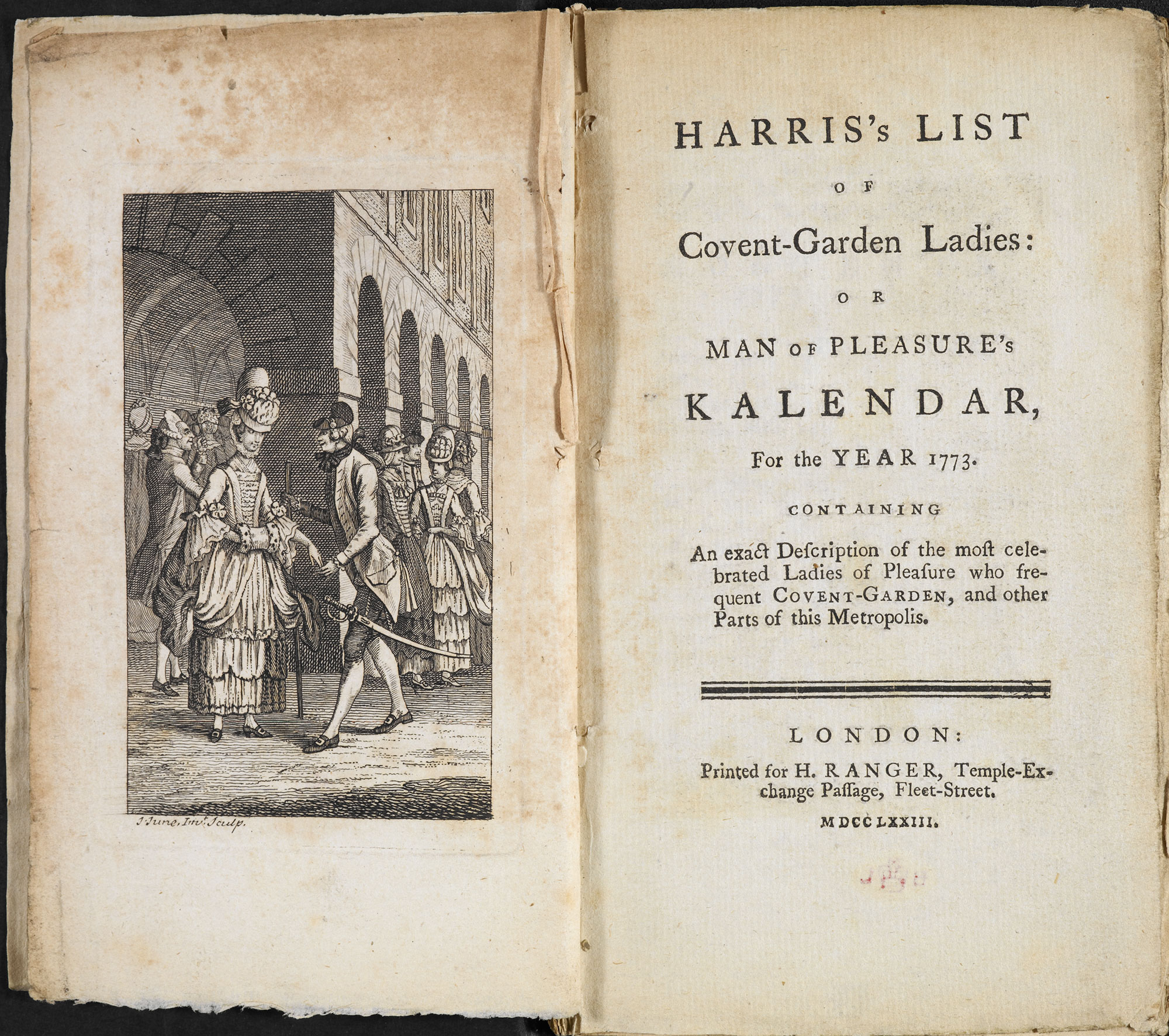

Each edition of Harris’s List opens with a frontispiece showing a mildly erotic stock image opposite the title page, which, from the 1760s to 1780s, is followed by a lengthy commentary on prostitution. This preamble argues that the prostitute is of benefit to the public, able to relieve man’s natural inclination towards violence. It describes the customer as a patron supportive of a good cause: “be your purse strings never closed; nor let the name of prostitute deter you from your pious resolve!”[9] Prostitutes were generally scorned by 18th-century society, and the 1789 edition’s preface complains “Why should the victims of this natural propensity … be hunted like outcasts from society, perpetually gripped by the hand of petty tyranny”, continuing: “Is not the minister of state who sacrifices his country’s honour to his private interest … more guilty than her?”[10]

Wikimedia Commons

At a basic level, the entries in Harris’s List detail each woman’s age, her physical appearance (including the size of her breasts), her sexual specialities, and sometimes a description of her genitals. Additional information such as how long she had been active as a prostitute, or if she sang, danced or conversed well, is also included.[11] Addresses and prices, which range from five shillings to five pounds, are provided.[12][b]Many of London’s prostitutes took customers back to the brothels they worked from, although most retired to lodgings.[13] The types of prostitute the lists present vary from “low-born errant drabs”, to prominent courtesans like Kitty Fisher and Fanny Murray; later editions contain only “genteel mannered prostitutes worthy of praise”.[9] The charms of a Mrs Dodd, who lived at number six Hind Court in Fleet Street, were listed in 1788 as “reared on two pillars of monumental alabaster”, continuing: “the symmetry of its parts, its borders enriched with wavering tendrils, its ruby portals, and the tufted grove, that crowns the summit of the mount, all join to invite the guest to enter.”[14] In the same edition, a similarly lurid description precedes the latter part of Miss Davenport’s entry, which concludes: “Her teeth are remarkably fine; she is tall, and so well proportioned (when you examine her whole naked figure, which she will permit you to do, if you perform the Cytherean Rites like an able priest) that she might be taken for a fourth Grace, or a breathing animated Venus de Medicis … she has a keeper (a Mr. Hannah) both kind and liberal; notwithstanding which, she has no objection to two supernumerary guineas.”[15] Miss Clicamp, of number two York Street near Middlesex Hospital, is described as “one of the finest, fattest figures as fully finished for fun and frolick as fertile fancy ever formed … fortunate for the true lovers of fat, should fate throw them into the possession of such full grown beauties.”[16] More characteristic of Harris’s List though, is the 1764 entry for Miss Wilmot, which tells of an amorous encounter with King George III’s brother, the Duke of York:

The Duke of York was only one of many famous men to have been mentioned in the lists; others included James Boswell, Ernest Augustus, King of Hanover, the clergyman William Dodd, Charles James Fox, George IV, William Hickey, Francis Needham, 1st Earl of Kilmorey, Robert Walpole and many others.[18]

Commentary

The women’s route into the sex trade, as described by the lists, is usually ascribed to youthful innocence, with tales of young girls leaving their homes for the promises of men, only to be abandoned once in London. Some entries mention rape, euphemistically described as women being “seduced against their will”. Lenora Norton was apparently “seduced” in such fashion, her entry elucidating on her experience, which occurred while she was still a child.[19] The “old urban legend”[20] of young girls being apprehended from the crowd by devious bawds is illustrated by William Hogarth’s A Harlot’s Progress,[21] but although in reality such stories were not unheard of, women entered into prostitution for a variety of reasons, often mundane. Rural immigrants in search of work could sometimes find themselves at the mercy of unscrupulous employers, or manipulated into the sex trade by underhand means. Some entries in Harris’s List illustrate how some women managed to lift themselves out of penury. Becky LeFevre, once a streetwalker, used her business sense to amass considerable wealth, as did a Miss Marshall and Miss Becky Child, who are each mentioned in several editions.[22] Many of these women had rich keepers, and some married wealthy aristocrats; Harriet Powell married Kenneth Mackenzie, 1st Earl of Seaforth, and Elizabeth Armistead married Charles James Fox.[23]

Elements of politicisation appear in some entries. The famed prostitute Betsy Cox’s 1773 listing describes how, when refused entry to a gathering of polite society at the newly opened Pantheon, she was helped by, among others, the Duke of Fife, who drew his sword to enforce her entry. Some lists also contain defences of prostitution; earlier editions claim that the trade guarded against the seduction of young women, provided an outlet for frustrated married men, and kept other young men from “le péche [sic] que la Nature désavoue [the sin that Nature repudiates]”, or sodomy.[24] However, no such views were expressed with regard to lesbianism, which in England, unlike sexual acts between men, has never been illegal. Miss Wilson of Cavendish Square thought that “a female bed-fellow can give more real joys than ever she experienced with the male part of the sex”, and Anne and Elanor Redshawe provided a discreet service in Tavistock Street, catering for “Ladies in the Highest Keeping” and other women who preferred to keep their activities private.[25]

A common complaint regarding street prostitution was the foul language used,[26] and while generally most entries in the lists look favourably on those women who refrained from swearing, the views expressed in the 1793 edition of Harris’s List tend towards equivocation. Mrs Cornish’s genteel nature was, on occasion, interrupted by “a volley of small shot”, and Miss Johnson’s proclivity towards “vulgarity of expression and a coarseness of manner” apparently suffered no shortage of admirers. Mrs Russell, attractive to “a number of clients among the youth, who are fond of beholding that mouth of the devil from whence all corruption issueth”, was admired for her “vulgarity more than any thing else, she being extremely expert at uncommon oaths”.[27] Drinking, intrinsically linked with prostitution, was also frowned on. Mrs William’s entry of 1773 is full of remorse, her having returned home “so intoxicated so as not to be able to stand, to the no small amusement of her neighbors”, and Miss Jenny Kirbeard had, in 1788, a “violent attachment to drinking”. Not all entries were disapproving though; Mrs Harvey would, in 1793, “often toss off a sparkling bumper,” while remaining “a lady of great sensibility … not a little clever in the performance of the act of friction.”[28] More generally, most entries are flattering, although some are less than complimentary; the 1773 listing for Miss Berry denounces her as “almost rotten, and her breath cadaverous”. Prostitutes may have paid money to appear in the lists, and in Denlinger’s view such commentary may indicate a degree of annoyance on the writer’s part, the women concerned perhaps having refused to pay.[29] Some listings also imply a degree of dissatisfaction on the part of the customer; in the 1773 edition, Miss Dean exhibited “great indifference” while entertaining her client, busying herself by cracking nuts while he was “acting his joys”. Others are scorned for wearing too much makeup, and some for being “lazy bedfellows”. A popular view that prostitutes were licentious, hot-blooded and hungry for sex was incompatible with the knowledge that most worked for money, and the lists therefore criticise women whose demands for payment appeared a little too mercenary.[30]

Possible authors

The identity of the lists’ authors is uncertain. Some editions may have been written by Samuel Derrick,[29] a Grub Street hack[31] born in 1724 in Dublin, who had moved to London to become an actor. With little success there, he had turned instead to writing, publishing works including The dramatic censor; being remarks upon the conduct, characters, and catastrophe of our most celebrated plays (1752), A Voyage to the Moon (1753) (a translation of Cyrano de Bergerac’s L’Autre Monde: ou les États et Empires de la Lune), and The Battle of Lora (1762). Derrick, who lived with the actress Jane Lessingham, was an acquaintance of Samuel Johnson18th-century English writer, critic, editor and lexicographer whose Dictionary of the English Language had far-reaching effects on the development of Modern English. and James Boswell.[32] The latter viewed him as “but a poor writer”,[33] while Johnson admitted that “if Derrick’s letters had been written by one of a more established name, they would have been thought very pretty letters.”[34]

Hallie Rubenhold’s 2005 book The Covent Garden Ladies sets out her interpretation of the story behind Harris’s List. She claims that John Harrison – otherwise known as Jack Harris, a savvy businessman and pimp who worked at the Shakespear’s Head Tavern in Covent Garden – was the list’s originator. Born perhaps around 1720–1730,[35] Harris apparently had expert knowledge of prostitutes working in Covent Garden and beyond, as well as access to rented rooms and premises for his clients’ use. He kept a record of the women he pimped and the properties he had access to, possibly in the form of a small ledger or notebook.[36] Derrick, having previously written The Memoirs of the Shakespear’s Head, and possibly also its companion piece, The Memoirs of the Bedford Coffee House, was probably familiar with the Shakespear’s Head. The former book details “Jack, a waiter … who presides over the Venereal Pleasures of this Dome”, and its author likely studied Harris as he went about his business. Which of the two men first thought to produce Harris’s List is unknown, but probably for a one-off payment Harris allowed his name to be attached to it. With his detailed knowledge of Covent Garden, and with help from various associates, Derrick was therefore able to write the first edition of Harris’s List in 1757. As an aspiring author and social climber he preferred not to associate himself publicly with such questionable material, and his name therefore does not appear on any editions.[37]

Printed and published by the pseudonymous H. Ranger, responsible for such works as Love Feasts; or the different methods of courtship in every country, throughout the known world,[1] the proceeds from the hugely successful first edition enabled Derrick to repay his debts, thereby freeing himself from a sponging houseA sponging house was a place of temporary confinement for those arrested for non-payment of a debt..[38] His fortunes changed for the better[39] when he became master of ceremonies at Bath and Tunbridge Wells in 1763.[32] His death on 28 March 1769 followed a protracted illness, but despite a significant income, he died penniless. He left no official will, but on his deathbed he bequeathed the 1769 edition of Harris’s List to Charlotte Hayes, his former friend and mistress, and a madam in her own right.[40] Hayes died in 1813.[41]

As the self-declared “Pimp General of All England”, the swaggering Harris amassed a considerable fortune, but his indiscretion proved to be his undoing. Prompted by reformers, in April 1758 the authorities began to hunt down and close “houses of ill fame”. Covent Garden was not spared, and the Shakespear’s Head Tavern was raided. Harris was caught, locked up in the local compter, and then imprisoned in Newgate.[42] He was released in 1761 and had some interests in publishing from 1765 to 1766, printing Edward Thompson’s The Courtesan, and later The Fruit-Shop and Kitty’s Atlantis, but he seems to have given this up late in 1766.[43] He became the proprietor of the Rose Tavern, not far from the Shakespear’s Head, but by the 1780s had delegated its running to an employee. The Rose was demolished about 1790, and for a few years Harris ran another tavern, the Bedford Head, with his son and daughter-in-law. He died sometime in 1792.[44] The Shakespear’s Head closed for business in 1804, and four years later the empty premises were badly damaged in the same fire that consumed the Covent Garden Theatre. What remained was subsumed by the neighbouring Bedford Coffee House.[45]

Later years

Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz claimed in 1791 that the lists were published by “a tavern-keeper, in Drury lane”, and that “eight thousand copies are sold annually.”[46] There is nothing to suggest that Hayes had any involvement with any edition other than that of 1769, and the list’s authors following Derrick’s death have not been identified. From the 1770s Harris’s List changes focus, moving away from the women of Covent Garden, to their stories. Its prose becomes more genteel, lacking the euphemisms which had helped make it so popular. These changes are echoed by the front cover, whose frontispiece becomes more gentrified. Material from earlier editions is recycled, and little attention is paid to accuracy. The responsibility for some of these changes can be attributed to John and James Roach, and John Aitkin, who from the late 1780s were the lists’ publishers.[47]

In 1795 the Proclamation Society, created several years earlier to help enforce King George III’s proclamation against “loose and licentious Prints, Books, and Publications, dispersing Poison to the minds of the Young and Unwary”, and “to Punish the Publishers and Vendors thereof”, brought Roach up on libel charges. In court he highlighted the list’s longevity, and claimed that “nobody had ever been prosecuted for publishing it; and, therefore, he was ignorant it was a libel.” When Lord Chief Justice Kenyon mentioned that a John Roach had previously been convicted for selling Harris’s List, Roach “assured his Lordship, that he had never been indicted before for this offence.”[48] He was nevertheless sentenced to one year in Newgate Prison, with sureties of £150 for three years, to ensure his good behaviour. Lord Justice Ashurst called the List “a most indecent and immoral publication”, and of Roach’s crime said “an offence of greater enormity could hardly be committed.”[49] Aitkin, indicted as John Aitken, may have been fined £200 for selling the same edition,[12] although Rubenhold contends that by then he had died.[50] After these trials, the list was no longer published. Only nine editions are extant: those for 1761, 1764, 1773, 1774, 1779, 1788, 1789, 1790 and 1793.[51]

Modern view

Wikimedia Commons

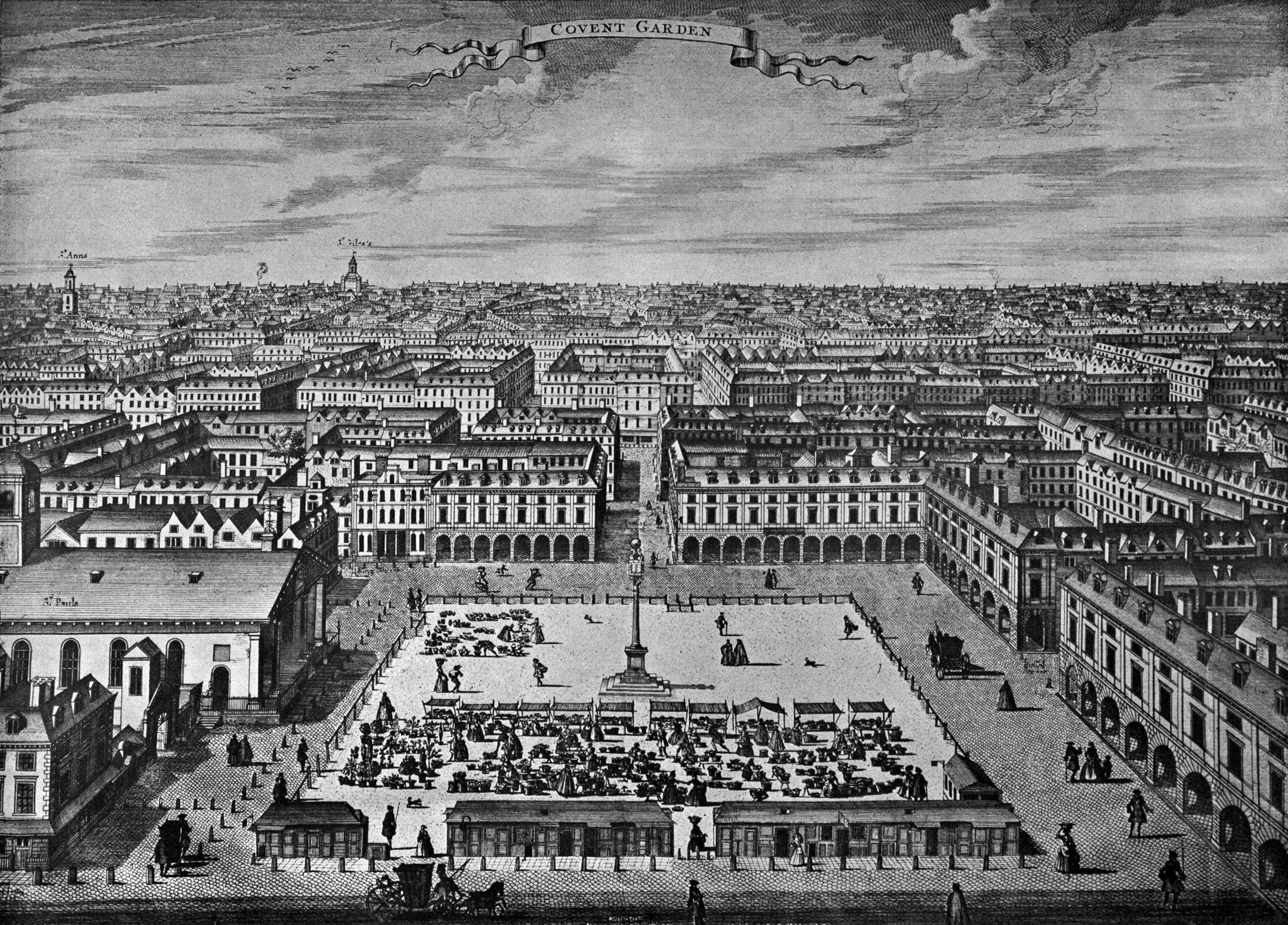

Harris’s List was published for a city rife with prostitution. London’s bawdy houses had, by the 1770s, disappeared from the poorer areas outside the city wall, and in the West End were found in four areas: St Margaret’s in Westminster; St Anne’s in Soho and St James’s; and most especially, with more than two thirds of London’s “Disorderly Houses”, around Covent Garden and the Strand.[52] The area was noted for its “great numbers of female votaries to Venus of all ranks and conditions”, while another author distinguished Covent Garden as “the chief scene of action for promiscuous amours.”[53] The Scottish statistician Patrick Colquhoun estimated in 1806 that of Greater London’s approximately 1 million citizens,[54] perhaps 50,000 women, across all walks of life, were engaged in some form of prostitution.[55]

Whether any of these women could confirm their addresses for publication in Harris’s List is something that the author Sophie Carter doubts. She views the annual as “primarily a work of erotica”, calling it “nothing so much as a shopping list … textually arrayed for the delectation of the male consumer”, continuing “they [the women] await his intervention to institute an exchange”,[56] epitomising the traditional male role in pornography. Elizabeth Denlinger includes a similar sentiment in her essay, “The Garment and the Man”: “This varied display of women to satisfy the ‘great itch’ … is a fundamental aspect of the sphere to which Harris’s List offered British men a carte d’entrée”.[57] Rubenhold writes that the variability in the descriptions of prostitutes over the years the list was published defy “all attempts to categorise it as either exclusively up-market or simply middle of the road.”[58] She suggests that the annual’s purpose was to “conduct the desirous to the embrace of a prostitute”,[9] and that its prose was designed for “solitary sexual enjoyment”[1] (H. Ranger also sold back-issues of Harris’s List). Sold to a London public which was mostly patriarchal, its listings reflect the prejudices of the men who wrote them. They were therefore not representative of women generally, and as she concludes, “it is likely that their stories would have differed quite significantly from those recounted by their customers for the benefit of the List’s publishers.”[59]

Not every commentator agreed with Colquhoun’s estimate, which became “the most widely quoted sum”,[60] but in the opinion of Cindy McCreery the fact that most people agreed there were far too many prostitutes in London is indicative of widespread concern about the trade.[61] Attitudes towards prostitution hardened at the end of the 18th century, with many viewing prostitutes as indecent and immoral,[62] and it was in this atmosphere that Harris’s List met its demise. Books such as the Wandering Whore and Edmund Curll’s Venus in the Cloyster (1728) are often mentioned alongside Harris’s as examples of erotic literature. Along with the anonymously written Fifteen Plagues of a Maidenhead (1707), Garfield and Curll’s works were involved in cases that helped form the 18th-century legal concept of “obscene libel” – which was a marked change from the previous emphasis on controlling sedition, blasphemy and heresy, traditionally the ecclesiastical courts’ province.[63] No laws existed to forbid the publication of pornography; therefore, when Curll was arrested and imprisoned in 1725 (the first such prosecution in almost twenty years), it was under threat of a libel charge. He was released a few months later, only to be locked up again for publishing other materials deemed offensive by the authorities.[64] Curll’s experience with the censors was uncommon, though, and prosecutions based on obscene publications remained a rarity. Although their court action spelled the end for Harris’s List, despite the best efforts of the Proclamation Society (later the Society for the Suppression of Vice), the publication of pornography continued apace; more pornographic material was published during the Victorian era than at any time previously.[65][c]The Obscene Publications Act 1857 was the first piece of legislation specifically enacted to suppress the sale of such material, although this is no longer in force, having been amended by more recent legislation.[66]

Notes

| a | By this the author means duodecimo-sized pages. |

|---|---|

| b | Many of London’s prostitutes took customers back to the brothels they worked from, although most retired to lodgings.[13] |

| c | The Obscene Publications Act 1857 was the first piece of legislation specifically enacted to suppress the sale of such material, although this is no longer in force, having been amended by more recent legislation.[66] |

References

- p. 119

- p. 52

- pp. 358, 370–372

- p. 54

- pp. 413–414

- p. 192

- p. 369

- p. 84

- p. 120

- pp. 375–376

- pp. 183–184

- p. 120

- p. 362

- p. 378

- p. 379

- p. 359

- p. 373

- pp. 299–301

- p. 292

- p. 126

- p. 77

- pp. 315–316

- pp. 285–287

- p. 376

- p. 147

- p. 385

- pp. 391–392

- pp. 388–389

- p. 371

- pp. 295–296

- pp. 75–76

- p. 527

- p. 528

- p. 262

- pp. 52–72

- pp. 102–117

- p. 117

- p. 2230230

- pp. 236–240

- p. 277

- pp. 178–186

- p. 205

- pp. 260–267

- p. 197

- pp. 277–280

- p. 372

- p. 280

- p. 285

- pp. 120–122

- p. 16

- pp. 340–341

- p. 55

- p. 360

- p. 121

- p. 295

- p. 178

- p. 41

- p. 70

- pp. 70–71

- pp. 37–38

- pp. 127–129