Wikimedia Commons

Victorian painting refers to the distinctive styles of painting in the United Kingdom during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837–1901). Victoria’s early reign was characterised by rapid industrial development and social and political change, transforming the United Kingdom into one of the most powerful and advanced nations in the world. Painting in the early years of her reign was dominated by the Royal Academy of Arts and by the theories of its first president, Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds and the academy were strongly influenced by the Italian Renaissance painter Raphael, and believed that it was the role of an artist to make the subject of their work appear as noble and idealised as possible. This had been a successful approach for artists in the pre-industrial period, when the main subjects of artistic commissions were portraits of the nobility and military and historical scenes. By the time of Victoria’s accession to the throne this approach was coming to be seen as stale and outdated. The rise of the wealthy middle class had changed the art market, and a generation who had grown up in an industrial age believed in the importance of accuracy and attention to detail, and that the role of art was to reflect the world, not to idealise it.

In the late 1840s and early 1850s, a group of young art students formed the Pre-Raphaelite BrotherhoodGroup of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael. as a reaction against the teaching of the Royal Academy. Their works were based on painting as accurately as possible from nature when able, and when painting imaginary scenes to ensure they showed as closely as possible the scene as it would have appeared, rather than distorting the subject of the painting to make it appear noble. They also felt that it was the role of the artist to tell moral lessons, and chose subjects which would have been understood as morality tales by the audiences of the time. They were particularly fascinated by recent scientific advances which appeared to disprove the biblical chronology, as they related to the scientists’ attention to detail and willingness to challenge their own existing beliefs. Although the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was relatively short-lived, its ideas were highly influential.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 led to a number of influential French Impressionist artists moving to London, bringing with them new styles of painting. At the same time, a severe economic depression and the increasing spread of mechanisation made British cities an increasingly unpleasant place to live, and artists turned against the emphasis on reflecting reality. A new generation of painters and writers known as the aesthetic movement felt that the domination of art buying by the poorly educated middle class, and the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on reflecting the reality of an ugly world, was leading to a decline in the quality of painting. The aesthetic movement concentrated on creating works depicting beauty and noble deeds, as a distraction from the unpleasantness of reality. As the quality of life in Britain continued to deteriorate, many artists turned to painting scenes from the pre-industrial past, while many artists within the aesthetic movement, regardless of their own religious beliefs, painted religious art as it gave them a reason to paint idealised scenes and portraits and to ignore the ugliness and uncertainty of reality.

The Victorian age ended in 1901, by which time many of the most prominent Victorian artists were dead. In the early 20th century, Victorian attitudes and arts became extremely unpopular. The modernist movement, which came to dominate British art, was drawn from European traditions and had little in common with 19th-century British works. Because Victorian painters had generally been extremely hostile towards these European traditions, they were mocked or ignored by modernist painters and critics in the first half of the 20th century. In the 1960s some Pre-Raphaelite works came back into fashion amongst elements of the 1960s counterculture, who saw them as a predecessor of 1960s trends. A series of exhibitions in the 1960s and 1970s further restored their reputation, and a major exhibit of Pre-Raphaelite work in 1984 was one of the most commercially successful exhibitions in the Tate Gallery’s history. While Pre-Raphaelite art enjoyed a return to popularity, non-Pre-Raphaelite Victorian painting remains generally unfashionable, and the lack of any significant collections in the United States has restricted wider knowledge of it.

Background

Wikimedia Commons

When the 18-year-old Alexandrina Victoria inherited the throne of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland as Queen Victoria in 1837, the country had enjoyed unbroken peace since the final victory over Napoleon in 1815.[4] In 1832 the Representation of the People Act (commonly known as the Reform Act) and its equivalents in Scotland and Ireland had abolished many of the corrupt practices of the British political system, giving the country a stable and relatively representative government.[5] The Industrial Revolution was underway, and in 1838 the London and Birmingham Railway opened, linking the industrial north of England to the cities and ports of the south;[6] by 1850 more than 6200 miles (9,977 km) of railways were in place and Britain’s transformation into an industrial superpower was complete.[7] The perceived triumph of technology, progress and peaceful trade was celebrated in the 1851 Great Exhibition, organised by Victoria’s husband Albert, which attracted over 40,000 visitors per day to view the more than 100,000 exhibits of manufacturing, farming and engineering on display.[8]

While Britain’s economy had traditionally been dominated by the landowning aristocracy of the countryside, the Industrial Revolution and political reforms had greatly reduced their influence, and created a booming middle class of merchants, manufacturers and engineers in London and the industrial cities of the north.[9] The newly rich were generally keen to show off their affluence through the display of art,[10] and rich enough to pay high prices for art works, but generally had little interest in the old masters, preferring modern works by local artists.[9] In 1844 Parliament ruled art unions legal, which commissioned artworks by famous artists, paying for them by means of a lottery in which the finished artwork was the prize; this not only offered an entrance to the art world for people who may not have been able to afford to buy a significant painting, but stimulated a growing market for prints.[11]

Reynolds and the Royal Academy

British painting had been strongly influenced by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792), the first president of the Royal Academy of Arts, who believed that the purpose of art was “to conceive and represent their subjects in a poetical manner, not confined to mere matter of fact”, and that artists should aspire to emulate the Italian Renaissance painter Raphael in making their subjects appear as close to perfection as possible.[12]

Wikimedia Commons

By the time of Victoria’s accession the Royal Academy dominated British art, with the annual Royal Academy Summer Exhibition the most important event in the arts world.[13] The Royal Academy also controlled the prestigious Royal Academy art schools, which taught with a very narrow focus on approved techniques.[13] Painting in Raphael’s style had proved commercially successful for artists serving a nobility primarily interested in family portraiture, military scenes and scenes from history, religion and classical mythology, but by the time of Victoria’s accession was coming to be seen as a dead end.[9] The destruction of the Houses of Parliament in late 1834, and the subsequent competitions to select artists to decorate its replacement, threw into sharp focus the lack of competent British artists able to paint historic and literary topics,[14] which at the time were considered the most important form of painting.[10][c]For a work to be considered for the new Houses of Parliament building, it was a condition that it depicted either English history, or a scene from the works of John Milton, William Shakespeare, or Edmund Spenser.[15] From 1841 the new, and highly influential, satirical magazine Punch increasingly ridiculed the Royal Academy and contemporary British artists.[15]

John Ruskin’s seminal Modern Painters, the first volume of which was published in 1843, argued that it was the purpose of art to represent the world and allow the viewer to form their own opinions of the subject, not to idealise it.[2] Ruskin believed that only by representing nature as accurately as possible could the artist reflect the divine qualities within the natural world.[15] An upcoming generation of young artists, the first to have grown up in an industrial age in which the accurate representation of technical detail was considered a virtue and a necessity, came to agree with this view.[2] In 1837 Charles Dickens began to publish novels attempting to reflect the reality of the problems of the present day, rather than the past or an idealised present; his writings were greatly admired by many of the rising generation of artists.[13]

In 1837 the painter Richard Dadd

English painter of the Victorian era , noted for his depiction of fairies and other supernatural subjects. Most were completed while he was an inmate of Bedlam and Broadmoor lunatic asylums. and a group of friends formed The Clique, a group of artists rejecting the Academy’s tradition of historical subjects and portraiture in favour of populist genre painting.[16] While the majority of The Clique returned to the Royal Academy in the 1840s,[16] after Dadd’s incarceration after he murdered his father in 1843, they were the first group of significant artists to challenge the positions of the Royal Academy.[13] The 1840s was the decade during which the Romantic Movement came to an end and the Victorian period began.[17]

J. M. W. Turner

|  |

Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire (1839) and Rain, Steam and Speed (1844) depicted the early stages of the Industrial Revolution. Wikimedia Commons | |

At the time of Victoria’s accession, the most significant living British artist was J. M. W. Turner. Turner had made his name in the late 18th century with a series of well-regarded landscape watercolours, and exhibited his first oil painting in 1796.[18] A staunch ally of the Royal Academy throughout his life, he was elected a full Royal Academician in 1802 at the age of 27.[18] In 1837 he resigned from his post as professor of perspective at the Royal Academy, and in 1840 first met John Ruskin. The first volume of Ruskin’s Modern Painters was a defence of Turner, arguing that Turner’s greatness had developed despite, not because of, the influence of Reynolds and a consequent desire to idealise the subjects of his paintings.[2]

By the 1840s, Turner was drifting out of fashion. Despite Ruskin’s defence of his work as being ultimately “an entire transcript of the whole system of nature”,[15] Turner (who by 1845 had become the oldest Academician and deputy president of the Royal Academy[19]) had come to be seen by younger artists as embodying bombast and wilfulness, and to be a product of an earlier, Romantic period out of touch with the modern age.[2]

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Wikimedia Commons

In 1848 three young students at the Royal Academy art schools,[20] William Holman HuntEnglish painter (1827–1910), one of the founding members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood., John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, formed the Pre-Raphaelite BrotherhoodGroup of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael. (PRB). The PRB rejected the ideas of Joshua Reynolds, and had a philosophy based on working from nature as accurately as possible wherever possible, and when it was necessary to paint from imagination to strive to show the event as it most likely would have happened, not in the way that would appear most attractive or noble.[21]

The PRB took their inspiration from scientific exhibitions, and felt this scientific approach was in itself an instrument of moral good.[21] The intensely laboured detail and attention to accuracy showed that hard work and dedication had gone into their paintings, and thus illustrated the virtue of work, as contrasted to the “loose, irresponsible handling” of the Old Masters’ techniques or the “defiant indolence” of Impressionism.[22] Also, they felt it was the duty of the artist to choose subjects which illustrated moral lessons of some kind.[22] Early PRB works were noted for their inclusion of flowers, which suited their purpose well. Flowers could be used in almost any scene, they could be used to convey messages in the then-popular language of flowers, and accurately illustrating them showed the artist’s dedication to scientific accuracy.[22]

Wikimedia Commons

The Victorian age was characterised by rapid scientific advance, and by rapidly changing attitudes to religion as advances in geology, astronomy and chemistry disproved the biblical chronology. The PRB found these advances fascinating, based as they were in attention to detail and a willingness to challenge existing beliefs on the basis of observed fact. PRB founder William Holman Hunt led a revolution in English religious art, visiting the Holy Land and studying archaeological evidence and the clothing and appearance of local people to paint biblical scenes as accurately as possible.[24]

By 1854 the PRB had collapsed as an organisation, but its style continued to dominate British painting.[20] An exhibit of Pre-Raphaelite works at the 1855 Paris Exposition Universelle was well-received.[25]

The 1857 Art Treasures Exhibition in ManchesterExhibition of fine art art held in Manchester in 1857, the largest art exhibition ever in the UK., which exhibited the works of contemporary artists alongside 2000 works by European masters, saw 1.3 million visitors, further increasing awareness of modern painting styles.[25] In 1856 the art collector John Sheepshanks presented his collection of modern paintings to the nation, which together with the exhibits from the Great Exhibition formed the South Kensington Museum in June 1857 (later divided into the Victoria and Albert Museum of visual arts and the Science Museum of engineering and manufacturing technology).[25]

Painting remained a field dominated by male artists at this time. In 1859 a petition by 38 female artists was circulated to all Royal Academicians requesting the opening of the Academy to women.[26] Later that year Laura Herford submitted a qualifying drawing to the Academy signed simply “A. L. Herford”; the Academy accepted it, and her as its first female student in 1860.[27][d]Herford died in 1870 at the age of 39.[27] The Slade School of Fine Art, founded in 1871, actively recruited female students.[26]

Love, lust and beauty

Wikimedia Commons

The Pre-Raphaelite movement splintered during the 1860s, with some of its adherents abandoning strict realism in favour of poetry and attractiveness. Particularly in the case of Rossetti, this tended to be embodied in paintings of women.[28] As with many other artists and writers of the time, as his religious faith waned Rossetti increasingly saw love as the most important subject.[28]

This move towards depicting the effects of love became explicit in Venus Verticordia (“Venus the turner of hearts”), painted by Rossetti in the mid-1860s.[28][e]Venus Verticordia was commissioned in 1863 or 1864. In 1867 Rossetti repainted it, replacing the original face with a portrait of Alexa Wilding.[29] The title and subject come from John Lemprière’s Bibliotheca Classica, and refers to a prayer to Venus to turn the hearts of Roman women away from debauchery and lust and back towards modesty and virtue.[30] Surrounding Venus, roses represent love, honeysuckle represents lust, and the bird represents the shortness of human life. She holds the Golden Apple of Discord and Cupid’s arrow, thought to be a reference to the Trojan War and the destructiveness of love.[31]

John Ruskin disliked the painting intensely. While it is now thought that his dislike of the painting was due to a dislike of the representation of the naked female form,[32] he claimed his issues with the painting were with the depiction of the flowers, writing to Rossetti to advise him that “They were wonderful to me, in their realism; awful – I can use no other word – in their coarseness: showing enormous power, showing certain conditions of non-sentiment which underlie all you are doing now”.[33] Ruskin’s hostility towards the painting led to a quarrel between Ruskin and Rossetti, and Rossetti drifted away from Pre-Raphaelite thinkings and towards the new doctrine of art for art’s sake expounded by Algernon Charles Swinburne.[34][35]

Animal painting

Since the time of George Stubbs (1724–1806), Britain has had a strong tradition of animal painting, a field which had gained respect owing to James Ward’s highly proficient animal paintings of the early 19th century.[36] Selective breeding of livestock, particularly dogs, had become highly popular, leading to a lucrative market in drawings and paintings of prize-winning animals.[36] In the early 19th century the Scottish Highlands experienced a dramatic upsurge in popularity among the wealthy of Britain, particularly for the opportunities they offered for hunting.[36] One painter in particular, Edwin Landseer (1802–1873), took the opportunity offered by the boom in Scottish travel, travelling to Scotland for the first time in 1824 and returning each year to hunt, shoot, fish and sketch.[37]

Wikimedia Commons

Landseer became well known for his paintings of the landscape, people and particularly wildlife of Scotland, to the extent that his paintings, along with the novels of Sir Walter Scott, became the primary means through which people in the rest of the United Kingdom came to picture Scotland.[39][f]Landseer was a child prodigy, and first exhibited at the Royal Academy at the age of 13. He was elected a full Royal Academician at the age of 29.[40] His works were in such high demand that the engraving rights (the right to make printed duplicates of a work) would generally sell for at least three or four times the sale cost of each work, and it was rare for a work of his to sell for less than £1000.[36] In 1840 Landseer suffered a bout of mental illness and suffered alcoholism and mental illness throughout the rest of his life, although he continued to work successfully.[41] In later years he became best known as the designer of the bronze lions at the base of Nelson’s Column, unveiled in 1867.[41]

Landseer and other animal painters such as Briton Rivière also became well known for sentimental paintings of dogs. Landseer’s The Old Shepherd’s Chief Mourner, showing a sheepdog sitting beside a coffin, was particularly well-regarded by John Ruskin, who described it as “a touching poem upon canvas, which, it cannot be doubted, has caused many a stout heart to ‘play the woman’ by moving it to tears”.[39] Many of the artists of the period were keen huntsmen, and accepted as a given that nature was inherently cruel and that learning to embrace this cruelty was a mark of manliness.[42] In this context, dogs exhibiting emotions were a highly popular topic in a time of rapidly declining religious faith, suggesting the possibility of a nobility within nature that transcended cruelty and the will to live as a driving force.[43]

Fairy painting

Main article: Fairy paintingGenre of art and illustration featuring small imaginary human-like creatures with magical powers, often with wings.

Wikimedia Commons

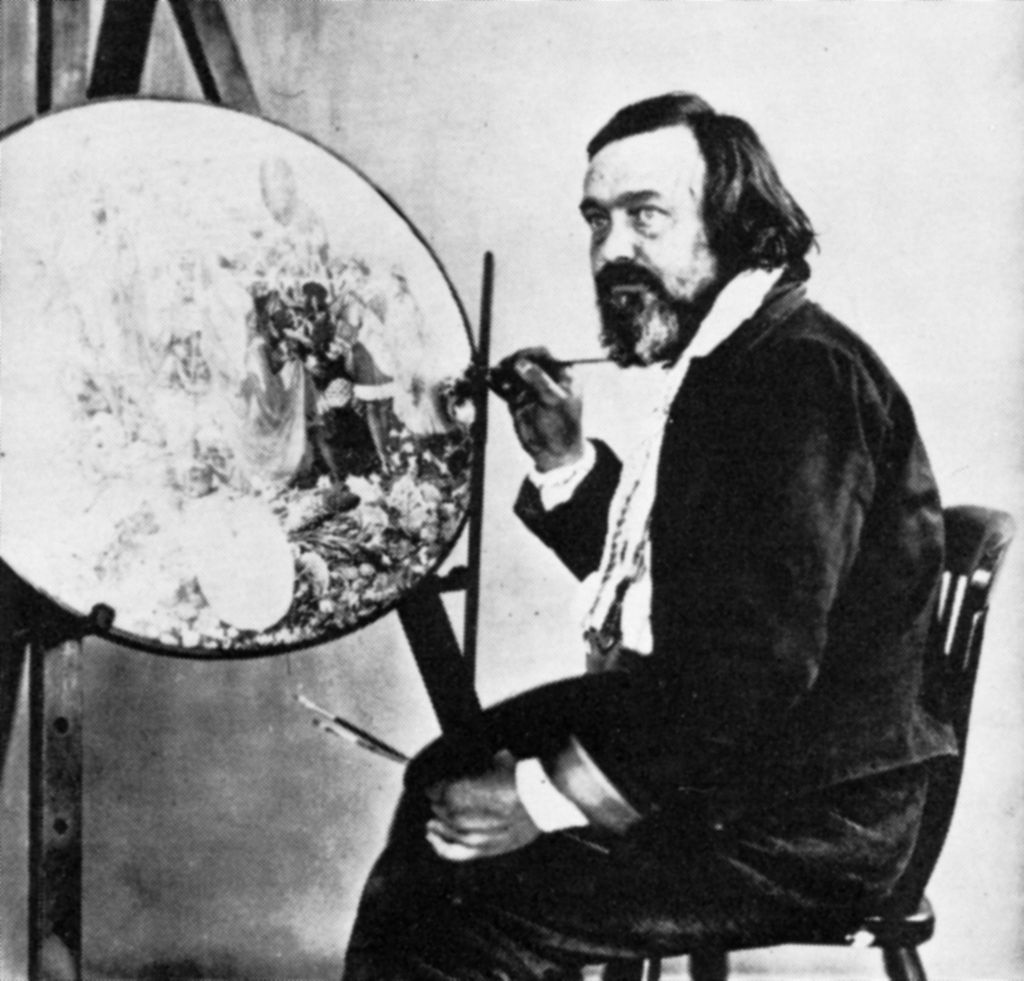

Fairy painting is a genre of art and illustration particularly fashionable during the Victorian period, featuring small imaginary human-like creatures with magical powers, often with wings. It was especially popular during the period 1840–1870, when its major practitioners included Joseph Noel PatonScottish artist, illustrator, antiquary, poet and sculptor.Scottish artist, illustrator, antiquary, poet and sculptor. and the “criminally insane” Richard Dadd,[44] who produced most of his work while incarcerated in the Bethlem psychiatric hospital for the murder of his father.[45]

The Victorian age exhibited a fascination with fairies and the supernatural,[46] but the popularity of the genre was also fuelled by the desire for new kinds of art by a growing middle-class audience.[47] The uprooting of long-standing tradition in the wake of industrialisation, and rapid advances in science and technology also played their part, encouraging a shift to fantasy subjects as a comforting distraction.[48]

Aesthetic movement

Wikimedia Commons

In the 1870s the Long Depression wrecked the economy and confidence of Britain, and the spirit of progress symbolised by the Great Exhibition began to fade, to the extent that in 1904 G. K. Chesterton described the Crystal Palace as “the temple of a forgotten creed”.[51] Some rising artists such as George Frederic Watts complained that the increasing mechanism of daily life, and the importance of material prosperity to Britain’s increasingly dominant middle class, were making modern life increasingly soulless.[52] The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 caused large numbers of French artists such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro to relocate to London, bringing with them new styles of painting.[53] Art critic Walter Pater’s The Renaissance, published in 1873, led a backlash against Pre-Raphaelitism, arguing that the only worthy way to conduct one’s life was through the pursuit of pleasure and the love of art and beauty for their own sakes.[54]

Wikimedia Commons

Against this background, a new generation of painters such as Frederic LeightonEnglish painter, knighted in 1878. and James Abbott McNeill Whistler departed from the traditions of storytelling and moralising, painting works designed for aesthetic appeal rather than for their narrative or subject.[54] Whistler disparaged the Pre-Raphaelite obsession with accuracy and realism, complaining that their audience had developed “the habit of looking not at a picture, but through it”.[55] The Pre-Raphaelites and their remaining champions protested vigorously against this new style of art,[55] as did the Royal Academy, leading Sir Coutts Lindsay to set up the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877 to show the work of artists overlooked by the Royal Academy.[56]

Matters reached a head in 1877, when John Ruskin visited an exhibition of Whistler’s Nocturne painting’s at the Grosvenor Gallery. He wrote of the painting Nocturne in Black and Gold – The Falling Rocket, that Whistler was “asking two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”. Whistler sued for libel, the case reaching the courts in 1878.[57] The judge in the case caused laughter in the court when, referring to Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge, he asked Whistler “Which part of the picture is the bridge?”; the case ended with Whistler awarded token damages of one farthingBritish coin with the value of one quarter of an old penny, 1/960 of a pound sterling.,[58] the costs of the trial driving him into bankruptcy.[56]

The aesthetic movement, as Pater and his successors came to be known, became increasingly influential; it was championed by Whistler and Oscar Wilde and until his death in 1883 by former Pre-Raphaelite Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and was popularised with the public by the successful Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera Patience.[56] The movement considered the rise of middle-class art buyers in Birmingham and Manchester, wealthy enough to buy art but insufficiently educated to show good taste, as having led to the decline of quality in British art.[59] Coupled with this, they felt that since industrialisation and capitalism were making the world increasingly unattractive, the emphasis of Pre-Raphaelite painters and those influenced by them upon reflecting reality as closely as possible was itself leading to the loss of beauty from art.[52] Consequently, the artists of the aesthetic movement saw the task of the artist as providing a distraction from the ugliness of reality for their viewers, readers and listeners,[52] and of trying to highlight and emphasise the beauty of the world and the nobility of good deeds, even if the artist no longer themselves believed in such things.[60][g]G. K. Chesterton, in his 1904 biography of Watts, attempted to describe the attitudes of artists who felt themselves surrounded by ugliness, in a culture in which the religious and political systems had been thrown into turmoil by scientific and social developments. ‘The attitude of that age … was an attitude of devouring and concentrated interest in things which were, by their own system, impossible or unknowable. Men were, in the main, agnostics: they said, “We do not know”; but not one of them ever ventured to say, “We do not care.” In most eras of revolt and question, the sceptics reap something from their scepticism: if a man were a believer in the eighteenth century, there was Heaven; if he were an unbeliever, there was the Hell-Fire Club. But these men restrained themselves more than hermits for a hope that was more than half hopeless, and sacrificed hope itself for a liberty which they would not enjoy; they were rebels without deliverance and saints without reward. There may have been and there was something arid and over-pompous about them: a newer and gayer philosophy may be passing before us and changing many things for the better; but we shall not easily see any nobler race of men. And its supreme and acute difference from most periods of scepticism, from the later Renaissance, from the Restoration and from the hedonism of our own time was this, that when the creeds crumbled and the gods seemed to break up and vanish, it did not fall back, as we do, on things yet more solid and definite, upon art and wine and high finance and industrial efficiency and vices. It fell in love with abstractions and became enamoured of great and desolate words.'[61] The 1878 election of Frederick Leighton as the Royal Academy’s president went some way to healing the breach within the British art world, as Leighton endeavoured to ensure the Summer Exhibition was open to young artists and artists working in new styles.[56]

Wikimedia Commons

The painters of the aesthetic movement prided themselves on their detachment from reality, working from studios and rarely mingling with the public.[59] Likewise, the subjects of their paintings were rarely engaged in activity of any kind; human figures typically stand, sit or lie still, generally with blank facial expressions.[62]

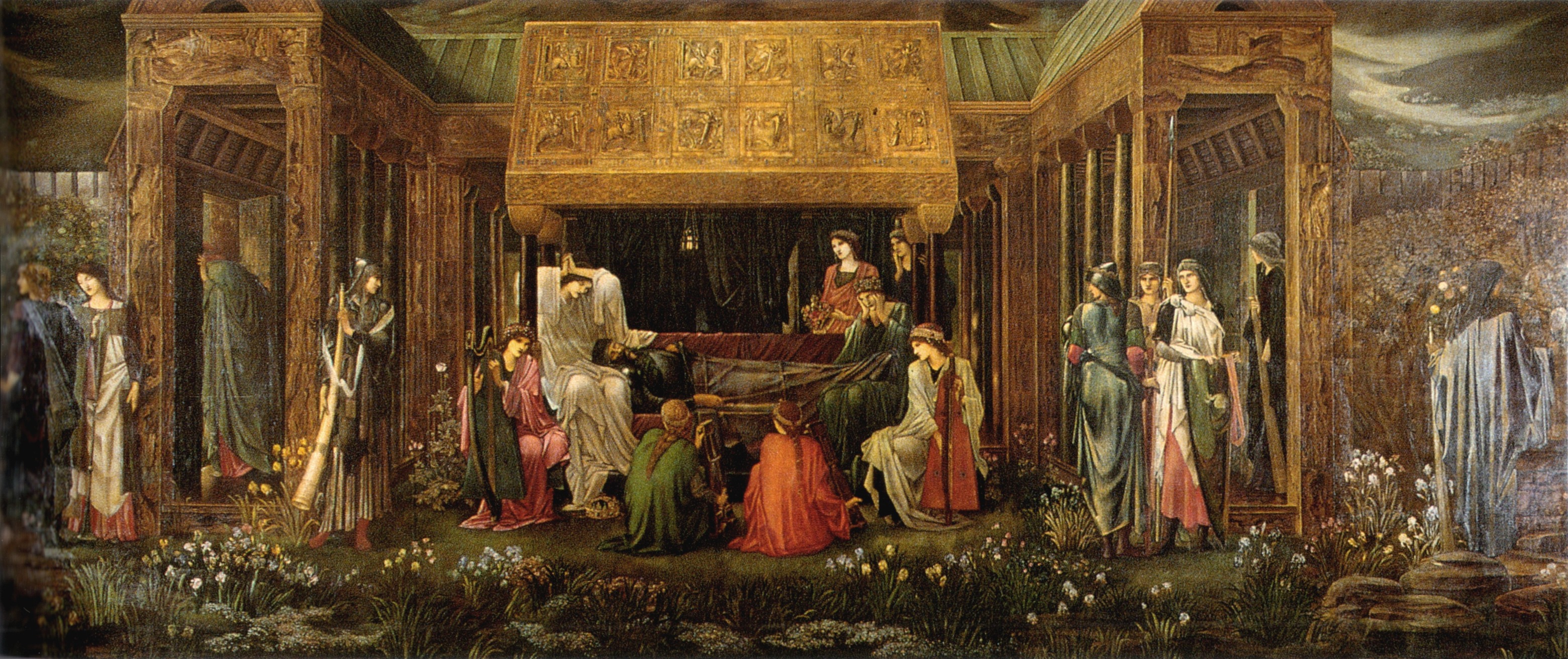

Classical revival

As the century progressed and the combination of mechanisation, economic decline, political chaos and religious faith made Britain an increasingly unpleasant place in which to live, the population increasingly came to look back to pre-industrial times as a golden age. As part of this trend, artists became drawn to pre-industrial subjects and techniques, and art buyers were particularly drawn to artists who could make connections between the present day and these idealised times such as to the Middle Ages, which were seen as the period in which the key institutions of modern Britain had begun and which had been popularised in the public imagination by the novels of Sir Walter Scott.[60]

Against this background there arose a great fashion for paintings on mediaeval themes, particularly Arthurian legend and religious themes. Many of the most noteworthy artists of the period, particularly from the aesthetic movement, chose to work on such themes despite their lack of religious faith, as it gave a legitimate excuse to paint idealised figures and scenes and to avoid reflecting the reality of industrial Britain.[64] (Edward Burne-Jones, who despite his lack of Christian belief was the most significant painter of religious imagery in the period, told Oscar Wilde that “The more materialistic science becomes, the more angels I shall paint”.[65])[h]Burne-Jones had studied to become a clergyman, but became a painter instead when he lost his faith. Despite his lack of faith, he painted Christian themes throughout his life and was in high demand from the Church of England as a designer of stained glass windows.[66] He was an entirely self-taught artist, other than a few informal lessons from Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1856.[67] Other painters took to painting different periods of the idealised past; Lawrence Alma-Tadema painted scenes of Ancient Rome,[60] former Pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais took to painting in the style of painters from the period immediately preceding the Industrial Revolution such as Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough,[60] and Frederic Leighton specialised in highly idealised scenes from Ancient Greece.[68][i]Leighton, like many other artists including Whistler and Burne-Jones, was heavily influenced by the collection of classical sculpture in the British Museum, particularly the Elgin Marbles. Records show that in the course of the 1870s, the number of students drawing in the British Museum rose more than five-fold.[69]

While there had been fashions for historical paintings before in British history, that of the late 19th century was unique. In previous revivals, dating from the Renaissance to the late 18th century, the ancient world symbolised greatness, dynamism and virility. In contrast, the aesthetic movement and their followers sought to emulate the most passive (and generally female) works of the classical world, such as the Venus de Milo.[70] Painters of this period emphasised passivity and internal drama, rather than the dynamism seen in previous works depicting the classical world.[70] They also, again unlike previous classical revivals, worked primarily in bright colours, rather than trying to suggest the bright but bleak appearance of classical stonework.[70][j]The use of bright colour to depict classical scenes was in part inspired by then-recent archaeological discoveries which indicated that classical statues had originally been painted. George Frederic Watts had been present at the excavation of the ruins of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, and had seen colour on surviving fragments of stonework as they were excavated.[70]

Not all members of the aesthetic movement subscribed to the backlash against the present in favour of an idealised past. Whistler, in particular, was scathing of this view, dismissing the sentiment as “this lifting of the brow in deprecation of the present – this pathos in reference to the past”.[60]

French influence and the rise of art colonies

Even among artists who did not paint pictures of the past, the influence of the backlash against modernity often had an effect. In landscape painting in particular, artists generally abandoned the effort to paint realistic depictions of views, and instead focused on effects of lighting, and on the capturing of elements of the pre-industrial countryside that they felt were likely to be destroyed.[73][k]Towards the end of the 19th century, as industrialisation, mechanisation and globalisation continued to spread, there was a genuine belief among some people that the whole of densely-populated England would become urbanised, and the countryside destroyed.[73] Country scenes, and images of country people (particularly farmers and fishermen and their families), became a highly popular topic both in Britain and throughout industrialising Europe.[73] Art colonies began to open in locations thought particularly picturesque, allowing artists and students to work in the countryside and meet genuine country people, while still in the company of like-minded people.[74] The most influential of these colonies was the Newlyn School in western Cornwall, which was heavily influenced by the style of Jules Bastien-Lepage in which individual brushstrokes remain visible, suggesting the coarse simplicity of the idealised country life.[71] The techniques introduced by the Newlyn School and other similar French impressionist styles such as those of Edgar Degas were in turn taken up by painters elsewhere in the country such as Walter Sickert, while John William WaterhouseEnglish artist known primarily for his depictions of women set in scenes from myth, legend or poetry. He is the best known of that group of artists who from the 1880s revived the literary themes favoured by the Pre-Raphaelites. fused backgrounds painted in Bastien-Lepage’s style with Pre-Raphaelite images of historical and classical legends.[71]

This spread of French techniques was viewed with deep scepticism by the preceding generation of painters. British painters had historically prided themselves on each having a distinct and easily recognisable style, and viewed French and French-influenced painters as being unduly similar to each other in style, and as John Everett Millais said “content to lose their identity in their imitation of their French masters”.[71] George Frederic Watts saw the rise of the French style as reflecting a growing culture of laziness within Britain as a whole, while William Holman Hunt was troubled by the lack of significance of the paintings’ subjects.[75] Despite Leighton’s reforms of the Royal Academy the Summer Exhibition remained mainly closed to these painters, leading to the foundation in 1886 of the New English Art Club as an exhibition space in London for French-influenced painters.[76] The New English Art Club in turn suffered a schism in 1889 between those painters who painted rural life and nature, and a faction led by Walter Sickert who felt themselves more influenced by impressionism and experimental techniques.[77]

Legacy

Wikimedia Commons

The opening of the Tate Gallery in 1897, opened to display sugar merchant Sir Henry Tate’s collection of Victorian art, proved the last triumph of Victorian painting.[78] Leighton and Millais had died the preceding year; Burne-Jones died in 1898, followed by Ruskin in 1900 and Victoria herself in 1901.[78]

In the 1910s, Victorian styles of art and literature fell dramatically out of fashion in Britain, and by 1915 the word “Victorian” had become a derogatory term.[79] Many people blamed the outbreak of the First World War, which devastated Britain and Europe, on the legacy of the Victorian age, and arts and literature associated with the period became deeply unpopular.[79] Lytton Strachey’s Eminent Victorians (1918) and Max Beerbohm’s Rossetti and His Circle (1922), both extremely successful and influential, brought parody of the Victorian age and Victorian artists into the literary mainstream, while the increasingly influential modernism movement, which came to dominate British art in the 20th century, drew its inspiration from Paul Cézanne and had little regard for 19th-century British painting.[79][l]The highly influential art critic Clive Bell declared that it should be the role of the painter to “not convey sentiments about morals and religion, but to create forms which have an emotional significance of their own”, dismissing Pre-Raphaelite art as “a sermon at a tea party”.[80]

Throughout the 20th century the work of the 19th-century French impressionists and post-impressionists rose in value and importance. Because the Pre-Raphaelites and the members of the aesthetic movement, who between them had dominated Victorian painting, had united in the late 19th century in condemnation of French influence and the perceived laziness and insignificance of impressionism and post-impressionism, they were mocked or dismissed by many modernist painters and critics in the first half of the 20th century.[75][m]Not all modernists condemned Victorian painting; the young Pablo Picasso was a great admirer of Burne-Jones.[75]

In the 1940s William Gaunt’s The Pre-Raphaelite Tragedy, coupled with a general desire during wartime to celebrate the achievements of British culture, led to a revival of interest in Victorian art.[81] A number of major British museums held events and exhibits in 1948 to mark the centenary of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood,[81] but fashionable art critics such as Wyndham Lewis mocked the PRB as a pretentious irrelevance.[10]

A major exhibition in 1951–1952 at the Royal Academy of Arts, The First Hundred Years of the Royal Academy 1769–1868 brought a number of British works from the 19th century to a wider audience,[81] but the general opinion of Victorian art remained low.[82]

In the 1960s some aspects of Victorian art became popular in the 1960s counterculture, as Pre-Raphaelitism in particular began to be seen as a precursor of Pop art and other contemporary trends.[81] A series of exhibitions on individual Pre-Raphaelite and PRB-influenced artists in the 1960s and 1970s further boosted their reputation, and a major exhibition in 1984 at what was then the Tate Gallery (now Tate Britain) showcasing the entire Pre-Raphaelite movement was one of the most commercially successful exhibitions in the gallery’s history.[81]

Non-Pre-Raphaelite Victorian art mainly remained unfashionable. In 1963 Flaming June, one of the most significant among Sir Frederic Leighton’s classicist pieces, went on the market in London at just £50 (about £1,000 in today’s terms),[81][83][n]Flaming June was bought by dealer Jeremy Maas, who struggled to find a museum willing to exhibit it. Maas eventually sold it to Puerto Rican industrialist Luis A. Ferré (later Governor of Puerto Rico), and it now forms the centrepiece of the Museo de Arte de Ponce.[81] and as late as 1967 art historian Quentin Bell felt able to write that Victorian art was “aesthetically and therefore historically negligible”.[84] Although non-Pre-Raphaelite Victorian art has experienced a slight revival in subsequent years it remains unfashionable, and the lack of any significant collections in the United States has limited global interest in the topic.[85]

Notes

| a | A Private View satirises the aesthetic movement of the late 19th century. Oscar Wilde speaks on his theories of beauty to a crowd of admirers, while John Everett Millais and Anthony Trollope ignore him. Frith specialised in crowd scenes and literary illustrations, and rejected Pre-Raphaelitism and the aesthetic movement, the two main artistic trends of English painting during Victoria’s reign, making himself unpopular with many of his contemporaries. His career spanned the entire Victorian period, with his first public exhibit in 1838 and his last in 1902.[1] |

|---|---|

| b | Victoria’s journal notes that while the infant Arthur did give Wellington a nosegay as shown, Wellington’s gift for the prince was in fact a golden cup, not a casket.[3] |

| c | For a work to be considered for the new Houses of Parliament building, it was a condition that it depicted either English history, or a scene from the works of John Milton, William Shakespeare, or Edmund Spenser.[15] |

| d | Herford died in 1870 at the age of 39.[27] |

| e | Venus Verticordia was commissioned in 1863 or 1864. In 1867 Rossetti repainted it, replacing the original face with a portrait of Alexa Wilding.[29] |

| f | Landseer was a child prodigy, and first exhibited at the Royal Academy at the age of 13. He was elected a full Royal Academician at the age of 29.[40] |

| g | G. K. Chesterton, in his 1904 biography of Watts, attempted to describe the attitudes of artists who felt themselves surrounded by ugliness, in a culture in which the religious and political systems had been thrown into turmoil by scientific and social developments. ‘The attitude of that age … was an attitude of devouring and concentrated interest in things which were, by their own system, impossible or unknowable. Men were, in the main, agnostics: they said, “We do not know”; but not one of them ever ventured to say, “We do not care.” In most eras of revolt and question, the sceptics reap something from their scepticism: if a man were a believer in the eighteenth century, there was Heaven; if he were an unbeliever, there was the Hell-Fire Club. But these men restrained themselves more than hermits for a hope that was more than half hopeless, and sacrificed hope itself for a liberty which they would not enjoy; they were rebels without deliverance and saints without reward. There may have been and there was something arid and over-pompous about them: a newer and gayer philosophy may be passing before us and changing many things for the better; but we shall not easily see any nobler race of men. And its supreme and acute difference from most periods of scepticism, from the later Renaissance, from the Restoration and from the hedonism of our own time was this, that when the creeds crumbled and the gods seemed to break up and vanish, it did not fall back, as we do, on things yet more solid and definite, upon art and wine and high finance and industrial efficiency and vices. It fell in love with abstractions and became enamoured of great and desolate words.'[61] |

| h | Burne-Jones had studied to become a clergyman, but became a painter instead when he lost his faith. Despite his lack of faith, he painted Christian themes throughout his life and was in high demand from the Church of England as a designer of stained glass windows.[66] He was an entirely self-taught artist, other than a few informal lessons from Dante Gabriel Rossetti in 1856.[67] |

| i | Leighton, like many other artists including Whistler and Burne-Jones, was heavily influenced by the collection of classical sculpture in the British Museum, particularly the Elgin Marbles. Records show that in the course of the 1870s, the number of students drawing in the British Museum rose more than five-fold.[69] |

| j | The use of bright colour to depict classical scenes was in part inspired by then-recent archaeological discoveries which indicated that classical statues had originally been painted. George Frederic Watts had been present at the excavation of the ruins of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus, and had seen colour on surviving fragments of stonework as they were excavated.[70] |

| k | Towards the end of the 19th century, as industrialisation, mechanisation and globalisation continued to spread, there was a genuine belief among some people that the whole of densely-populated England would become urbanised, and the countryside destroyed.[73] |

| l | The highly influential art critic Clive Bell declared that it should be the role of the painter to “not convey sentiments about morals and religion, but to create forms which have an emotional significance of their own”, dismissing Pre-Raphaelite art as “a sermon at a tea party”.[80] |

| m | Not all modernists condemned Victorian painting; the young Pablo Picasso was a great admirer of Burne-Jones.[75] |

| n | Flaming June was bought by dealer Jeremy Maas, who struggled to find a museum willing to exhibit it. Maas eventually sold it to Puerto Rican industrialist Luis A. Ferré (later Governor of Puerto Rico), and it now forms the centrepiece of the Museo de Arte de Ponce.[81] |

References

- p. 21

- p. 17

- p. 221

- p. 217

- p. 209

- p. 18

- p. 19

- p. 12

- p. 46

- p. 20

- p. 44

- p. 15

- p. 45

- p. 22

- p. 16

- p. 236

- p. 237

- p. 47

- p. 22

- p. 23

- p. 24

- p. 25

- p. 48

- p. 49

- p. 31

- p. 40

- p. 41

- p. 28

- p. 30

- p. 50

- p. 88

- p. 226

- p. 89

- p. 90

- p. 227

- p. 94

- p. 91

- p. 9

- pp. 11–21

- p. 34

- p. 71

- p. 10

- p. 30

- p. 51

- p. 26

- p. 27

- p. 52

- p. 122

- p. 28

- p. 31

- p. 12

- p. 29

- p. 32

- p. 237

- pp. 32–33

- p. 219

- p. 34

- p. 16

- p. 35

- p. 37

- p. 36

- pp. 36–37

- p. 38

- pp. 53–54

- p. 54

- p. 55

- p. 11

- pp. 109–111

- p. 12

- p. 13

- p. 36

- p. 13

Bibliography

This article may contain text from Wikipedia, released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.