William Holman Hunt (2 April 1827 – 7 September 1910) was an English painter, one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Group of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael.. His paintings were notable for their great attention to detail, vivid colour, and elaborate symbolism. These features were influenced by the writings of John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle, according to whom the world itself should be read as a system of visual signs. For Hunt, it was the duty of the artist to reveal the correspondence between sign and fact. Of all the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Hunt remained most true to their ideals throughout his career, always keen to maximise the popular appeal and public visibility of his works.[1]

Group of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael.. His paintings were notable for their great attention to detail, vivid colour, and elaborate symbolism. These features were influenced by the writings of John Ruskin and Thomas Carlyle, according to whom the world itself should be read as a system of visual signs. For Hunt, it was the duty of the artist to reveal the correspondence between sign and fact. Of all the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Hunt remained most true to their ideals throughout his career, always keen to maximise the popular appeal and public visibility of his works.[1]

Hunt was born at Cheapside in the City of London, as William Hobman Hunt, to warehouse manager William Hunt (1800–1856) and Sarah (c. 1798–1884), daughter of William Hobman, of Rotherhithe.[1] Hunt adopted the name “Holman” when he discovered that a clerk had misspelled his name that way after his baptism at the Anglican church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Ewell.[2]

Early career

Hunt’s father disapproved of his son’s ambition to become a professional painter, and so, at the age of twelve, Hunt secured a position as a copying clerk to a Spitalfields estate agent and auctioneer, James Labram, who introduced him to oil painting. During this period, Hunt studied drawing at a mechanics’ institute in the evenings, and spent his salary on weekly lessons with a City portrait painter, Henry Rogers. After eventually entering the Royal Academy Schools as a probationer, on his third attempt, Hunt was accepted as a full student on 18 December 1844, and the following year made his exhibition début at the Royal Manchester Institution with Pity the Sorrows of a Poor Old Man.[1]

In 1848 Hunt, together with the poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the painter John Everett Millais, formed the Pre-Raphaelite movement Group of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael., the aim of which was to revitalise English art by rejecting what they saw as the formulaic Classical poses made popular by the High Renaissance painter and architect Raphael (1483–1520), which they believed had a “corrupting” influence on the academic teaching of art.[3]

Group of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael., the aim of which was to revitalise English art by rejecting what they saw as the formulaic Classical poses made popular by the High Renaissance painter and architect Raphael (1483–1520), which they believed had a “corrupting” influence on the academic teaching of art.[3]

Later career

Hunt achieved some initial success with his vividly naturalistic scenes of modern rural and urban life, such as The Hireling Shepherd (1851) and The Awakening Conscience (1853). But he really rose to prominence with his religious paintings, and in particular The Light of the World (1854), “arguably the most famous religious image of the nineteenth century”.[1]

Hunt’s inherent nationalism came to the fore in the 1880s, with his resistance to the growing French influence on British art, but he was very open to the idea of religious experiences transcending any religion. His last oil painting, an almost full-size replica of The Light of the World, was created as a protest against the owner’s of the original, Keble College Oxford, charging visitors to see it, describing the college authorities as “bigotted Goths”. In his replica, Hunt added a crescent-shaped aperture to the lantern, suggesting that the light of God was available to Muslims as well as to Christians.[1]

Personal life

Hunt married Fanny Walker (1833–1866) on 28 December 1865. The following year the couple set out from England on a trip to the East, but their plans were disrupted by a cholera outbreak in Marseilles, so instead they settled in Florence. There, Fanny gave birth to a son, Cyril Benoni, but she never recovered from the childbirth, and a few weeks later died of miliary feverOutdated medical term for any infection characterised by a seed-like rash..[1]

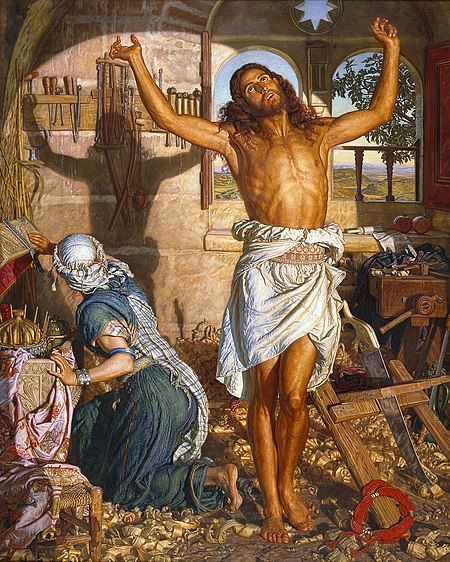

Hunt returned to England in October 1867, before returning to Florence the following year to supervise the elaborate marble tomb that he had designed for his wife in the shape of an ark on the waters. He then went on to Jerusalem, where he began preparatory work on The Shadow of Death, which he completed after his return to London in July 1872.[1]

In June 1873 Hunt became engaged to his late wife’s youngest sister (Marion) Edith (1846–1931), but such a union between a man and his deceased wife’s sister was at the time proscribed under English law.[a]The Marriage Act of 1835 had introduced a ban on marriage between a widower and his deceased wife’s sister, but such a union was still recognised if it took place in a foreign jurisdiction where it was legal. It was not until the Deceased Wife’s Sister Marriage Act of 1907 Act of Parliament making it legal for the first time in the United Kingdom for a man to marry his dead wife's sister. that a man was legally allowed to marry his deceased wife’s sister. To circumvent that restriction the couple arranged to be married at Neuchâtel in Switzerland on 8 November 1875, and sailed from Venice to Alexandria the following month, en route for Jerusalem.[1]

Act of Parliament making it legal for the first time in the United Kingdom for a man to marry his dead wife's sister. that a man was legally allowed to marry his deceased wife’s sister. To circumvent that restriction the couple arranged to be married at Neuchâtel in Switzerland on 8 November 1875, and sailed from Venice to Alexandria the following month, en route for Jerusalem.[1]

In 1903 the Hunts moved to 18 Melbury Road, Kensington, London. His advancing glaucoma made it increasingly difficult for him to continue painting, so he concentrated instead on his memoirs. While on holiday at Sonning-on-Thames, Berkshire in August 1910 Hunt contracted what at first appeared to be a slight chill, but he subsequently became critically ill and returned to his London home on 6 September. By 12:30 pm the following day he was dead, the cause of death given as “emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and respiratory and cardiac failure”. The funeral took place on 10 September at Golders Green crematorium, and Hunt’s ashes were buried in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral two days later, next to the grave of the painter J. M. W. Turner.[1]

Partial list of works

Created by the English artist William Holman Hunt in 1853, the painting was for a time the most talked about of the century.

Created by the English artist William Holman Hunt in 1853, the painting was for a time the most talked about of the century. Created by the English artist William Holman Hunt in 1853, the painting was for a time the most talked about of the century. (1853)

Created by the English artist William Holman Hunt in 1853, the painting was for a time the most talked about of the century. (1853)Wikimedia Commons

- Pity the Sorrows of a Poor Old Man (1845)

- Dr Rochecliffe Performing Divine Service in the Cottage of Joceline Joliffe, at Woodstock (1847)

- Rienzi vowing to obtain justice for the death of his young brother, slain in a skirmish between the Colonna and Orsini factions (1848)

- A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids (1850)

- The Hireling Shepherd (1851)

- Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus (1851)

- Our English Coasts (1852), also known as Strayed Sheep

- The Awakening Conscience

Created by the English artist William Holman Hunt in 1853, the painting was for a time the most talked about of the century.

Created by the English artist William Holman Hunt in 1853, the painting was for a time the most talked about of the century. Created by the English artist William Holman Hunt in 1853, the painting was for a time the most talked about of the century. (1853)

Created by the English artist William Holman Hunt in 1853, the painting was for a time the most talked about of the century. (1853) - The Light of the World (1854)

- The Scapegoat (1856)

- The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple (1860)

- Isabella and the Pot of Basil

Oil painting by William Holman Hunt, depicting a story in Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron. (1868)

Oil painting by William Holman Hunt, depicting a story in Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron. (1868) - The Shadow of Death (1872)

- The Importunate Neighbour (1895)

- The Miracle of the Holy Fire (1899)

Notes

| a | The Marriage Act of 1835 had introduced a ban on marriage between a widower and his deceased wife’s sister, but such a union was still recognised if it took place in a foreign jurisdiction where it was legal. It was not until the Deceased Wife’s Sister Marriage Act of 1907 Act of Parliament making it legal for the first time in the United Kingdom for a man to marry his dead wife's sister. that a man was legally allowed to marry his deceased wife’s sister. Act of Parliament making it legal for the first time in the United Kingdom for a man to marry his dead wife's sister. that a man was legally allowed to marry his deceased wife’s sister. |

|---|