Mining disasters in Lancashire in which five or more people were killed occurred most frequently in the 1850s, 1860s and 1870s. Many more miners were killed in everyday accidents than in the major disasters that had a catastrophic on mining communities, leaving widows and orphans without breadwinners.[1] Among the earliest deaths recorded in parish registers is that of Ffrancis Taylior, who lost his life in 1662 after a fall in a “coale pitte”.[2]

Most fatalities were caused by firedampDamps is a collective name given to all gases other than air found in coal mines in Great Britain. The chief pollutants are carbon dioxide and methane, known as blackdamp and firedamp respectively. , some by the miners who took the tops off the safety lamps that were designed to protect them because of the poor light they gave out. Some mine owners turned a blind eye to the use of candles in even the gassiest coal seams.[3]

To regulate working conditions, the government passed Acts of Parliament: the 1842 Act prohibited the employment of females and boys under 10 years old and appointed a single inspector, but inspections were few and breaches were common. Acts passed in subsequent years led to the appointment of more inspectors and increased their powers to regulate how mines were operated and the working conditions and welfare of the miners.[5]

The spate of disasters on the Lancashire CoalfieldThe Lancashire and Cheshire Coalfield in North West England was one of the most important British coalfields. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period more than 300 million years ago. in the late 1860s and early 1870s left authorities unable to cope with large numbers of widows and orphans whose main breadwinner had been killed. The Lancashire and Cheshire Miners Permanent Relief SocietyForm of friendly society started in 1872 to provide financial assistance to miners who were unable to work after being injured in industrial accidents in collieries on the Lancashire Coalfield. , championed by the Wigan miners’ agent, William Pickard, was started in 1872, when Lancashire was the country’s seventh largest coal producer and often had the highest accident figures.[4]

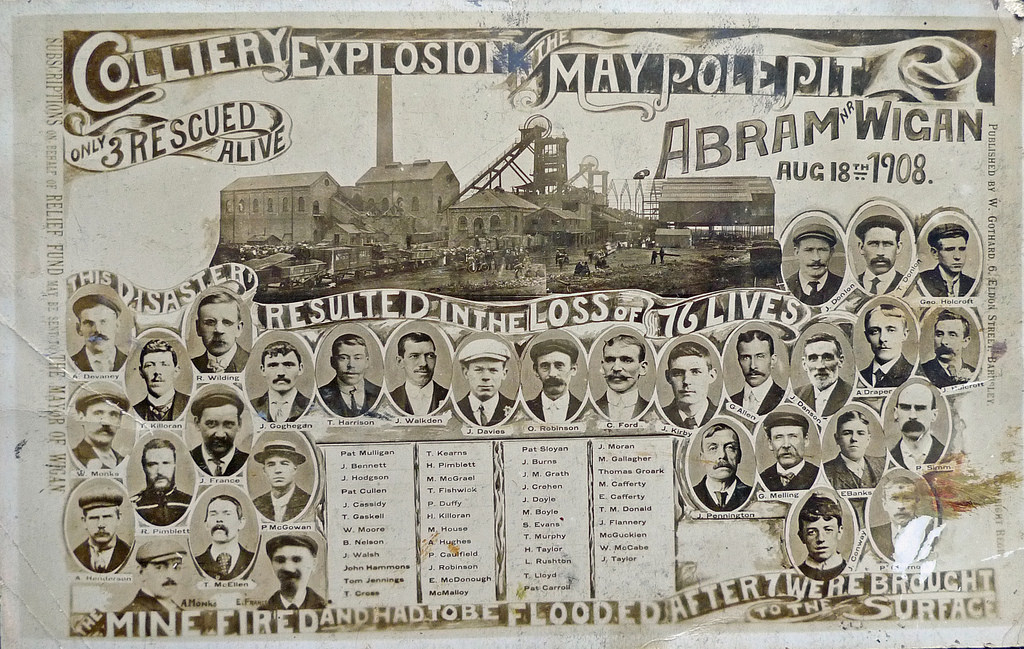

In the aftermath of a disaster the first rescuers were colliery managers and volunteer colleagues, who descended into the pits to look for signs of life, rescue the injured, seal off underground fires and recover bodies. Working in dangerous conditions, sometimes at great cost to themselves, their only specialised equipment was safety lamps to detect gases.[5] They were the predecessors of the mines rescueSpecialised job of rescuing miners and others who have become trapped or injured in underground mines because of accidents, roof falls or floods and disasters such as explosions caused by firedamp. teams recommended in a Royal Commission in 1886, but not made compulsory until the Coal Mines Act 1911.[5] In 1906 a committee of the Lancashire and Cheshire Coal Owners Association decided to provide a mines rescue station at Howe BridgeFirst mines rescue station on the Lancashire Coalfield, opened in 1908 in Lovers Lane Howe Bridge, Atherton, Lancashire, England. . Its trained rescuers were present at the Maypole and Pretoria Pit disasters.They also trained teams of men in pits throughout the coalfield. Boothstown Mines Rescue StationMines rescue station serving the collieries of the Lancashire and Cheshire Coal Owners on the Lancashire Coalfield, opened in 1933. opened in November 1933 close to the East Lancashire Road.[6] It replaced stations at Howe Bridge, Denton, St Helens and Burnley.[5]

Disasters by decade

References

- p. 7

- p. 217

- p. 9

- p. 158

- p. 134

- p. 213

- p. 14

- p. 16

- p. 18

- p. 62

- p. 1

- p. 3

- p. 122

- p. 4

- p. 9

- p. 26

- p. 18

- p. 19

- p. 28

- p. 32

- p. 24

- p. 38

- p. 33

- p. 36

- pp. 39–44

- p. 47

- pp. 43–49

- p. 48

- p. 53

- p. 55

- p. 59

- pp. 60–62

- p. 66

- pp. 62–64

- p. 67

- pp. 71–73

- pp. 74–75

- p. 79

- p. 81

- pp. 91–94

- pp. 94–96

- pp. 96–100

- p. 220

- pp. 104–106

- pp. 109–115

- p. 116

- pp. 118–134

- pp. 134–139

- p. 221

- pp. 146–161

- p. 69