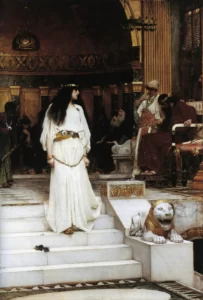

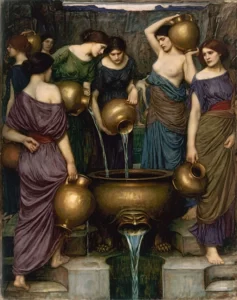

John William Waterhouse (1849–1917) was an English artist known primarily for his depictions of women set in scenes from myth, legend or poetry. He is the best known of the group of artists who from the 1880s revived the literary themes favoured by the Pre-RaphaelitesGroup of English artists formed in 1848 to counter what they saw as the corrupting influence of the late-Renaissance painter Raphael., although not themselves necessarily employing their techniques.[1]

Throughout his career Waterhouse returned repeatedly to the theme of the classical sorceress, as seen in his series of paintings of Circe, beginning with his Circe Offering the Cup to UlyssesOil painting in the Pre-Raphaelite style by John William Waterhouse, created in 1891. , 1891.[2]

Personal life

Documentation and records of Waterhouse’s personal life and character are patchy.[3] Modern-day historians and academics including Peter Trippi and Anthony Hobson believe that diaries, correspondence and journals were discarded or destroyed; there is also only scant detail or mention of Waterhouse in the letters of his contemporaries.[3][4]

Childhood

Baptised on 6 April 1849 in Rome, Waterhouse is thought by Trippi to have been born between 1 and 23 January that year.[5][a]Waterhouse’s exact date of birth is uncertain; an Italian birth certificate, which has since been mislaid, gave a date of 6 April but church records indicate that as the date of his baptism, a service not normally undertaken immediately a child is born.[5] The birth date on Waterhouse’s gravestone is now illegible, but Trippi notes that R.J.T.Cartwright saw the gravestone in the 1970s before it deteriorated and it displayed 16 January.[6] In his publications of 1980 and 1989 about Waterhouse, Hobson quotes 6 April 1849 as the date of birth.[7][8] The eldest of the four children born to William WaterhouseEnglish artist; father of John William Waterhouse (1816–1890) and his second wife Isabella MacKenzieEnglish portrait painter; mother of John William Waterhouse (c. 1821–1857),[9] the couple nicknamed him “Nino”, a pet name he employed until his death.[5][b]The nickname is a diminutive for Giovannino (Little John).[5] His parents were English, his father from Heckmondwike, West Yorkshire and his mother from Brompton;[10] both were artists who had exhibited at the Royal Academy.[11] Isabella concentrated on portraits while William predominantly focused on copying Old Masters, but also produced figure subjects and portraits.[12] The couple married on 5 February 1848 at Kensington, shortly afterwards moving to Rome, where William had been living intermittently since 1846.[13] Political unrest in the city led to the family relocating to a farmhouse in the Alban Hills near Frascati for a couple of years before returning to Rome.[11] Eventually, in 1854, the household permanently returned to England, living for a brief period at Brompton with Isabella’s father before moving to an upper middle-class area of Kensington where a house was newly built to accommodate their expanding family.[14][c]The four Waterhouse children were: John William; Edwin, baptised in 1850; Jessie, born in 1853; and Charles, their only child born in England, baptised in 1856.[15]

Education and training

When Waterhouse was eight, in 1857, his mother died of tuberculosis; three years later his father remarried, profoundly affecting the lives of Isabella’s children. The young Waterhouse was sent away to Leeds to be educated, although it is uncertain exactly which school, precisely where, whether he lived with relatives, or was enrolled as a boarder.[14] He did not excel at schoolwork but did display a penchant for sketching, although not sufficiently strongly to indicate any deep desire to become an artist. Engineering was one of the disciplines he considered following as a career. Specific interests included ancient history, especially Roman, with Waterhouse listing Smith’s Classical Dictionary as one of the school books he read with pleasure several times.[16] He was tutored in mythology, literature and Latin together with classical narratives; Trippi suggests the teenage Waterhouse probably read Tennyson’s Arthurian legends and Homer’s Odyssey.[17]

After leaving school Waterhouse returned to London, starting to work in his father’s studio undertaking mundane tasks such as completing the backgrounds of portraits William produced.[18] Taking advantage of the family’s base in the vicinity of the South Kensington Museum,[d]Now the Victoria and Albert Museum.[19] Waterhouse spent his spare time sketching there, in the National Gallery or the British Museum.[19] Four or five years passed in this fashion, by the end of which Waterhouse decided he wished to pursue a career in art.[20] Initially, Waterhouse submitted a drawing to seek admission at the Royal Academy as a painter but it was not accepted by the panellists. He was eventually admitted as a probationer at the Academy on 28 July 1870 although it was as a sculptor rather than an artist; the route taken was also unusual as, instead of receiving any formal training, his tutelage came from his father. Full admission as a student sculptor came on 23 January 1871 after he received the support of his father’s friend, Frederick Richard Pickersgill.[21][e]Pickersgill held the office of Keeper at the Royal Academy from 1873 until 1887.[22] Contemporary biographers, Alfred Lys Baldry and Rose E. D. Sketchley, disagree on the length of his trainee period; Sketchley indicates he attended in the evenings for two or three years, whereas Baldry states it only spanned a few months.[23]

Marriage

Waterhouse married fellow artist Esther KenworthyEnglish artist, specialist in flower painting; her husband was fellow artist John William Waterhouse on 8 September 1883 at the parish church of St Mary in Ealing.[24][f]Trippi suggests that, despite the couple opting to be married in a Church of England, Waterhouse’s captivation with ritual magic as subjects reflects an interest in the occult.[25] Historical convention within the Kenworthy family is that the couple may have met via associations with her father in Yorkshire or, as suggested by Trippi, they possibly become acquainted when they were both exhibiting at the Academy.[26] They had no children;[27] Hobson states that this was Esther’s choice, possibly because her own childhood had been spent in a house filled to capacity by young boys boarding at the school run by her parents at their home, together with the large number of her siblings.[28]

Career

At the onset of his career, Waterhouse tended to produce work sharing characteristics with that of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, although on a grander size and using a bolder technique in the application of the paint.[1] During the period from 1872 until 1876 his paintings did not follow specific themes,[29] but generally portrayed classical scenes or those from ancient history.[1] Early works were exhibited at the Dudley Gallery, the Society of British Artists (SBA) and other London venues;[30] his first exhibition painting, Undine, was submitted to the SBA Winter showing in 1872, where it was sold for 18 guineas.[31] The subject matter for his introduction as a Royal Academy exhibitor in 1874 was an allegory, Sleep and his half-brother DeathOil on canvas painting completed by John William Waterhouse in 1874.[29] An unusual topic for Victorian painters at the time, it was received favourably by reviewers.[32]

Two years later Waterhouse’s submission After the Dance was displayed in the coveted position “on the line”.[33] Alma-Tadema had sent a painting with the same title to the exhibition; contemporary reviewers felt Alma-Tadema’s nude Bacchante[g]Or maenad highlighted flaws in the painter’s skills, whereas Waterhouse presented the dancers in a less offensive manner as they were “gracefully draped”.[34] Waterhouse again secured prime position the following year with A Sick Child Brought into the Temple of Aesculapius, another painting that revealed some influences from Alma-Tadema’s brushwork techniques with a lively stroke provided with a generally flat surface. Yet it also demonstrated subtle deviations, by being so large as to envelope observers while garnering sympathetic emotional reactions in contrast to Alma-Tadema’s aim of not appealing to viewers emotions.[35]

The money Waterhouse earned from the sale of his paintings allowed him to spend time travelling and studying abroad, including a return to Italy, together with the opportunity to further develop his skills. During this period he produced a string of Roman-themed paintings, including The Remorse of Nero after the Murder of his Mother.[36] In later years, Waterhouse expressed dissatisfaction with the series of works rendered while abroad, deeming them “rubbish”,[37] but Sketchley recorded that the paintings were liked by the general populace.[38]

Waterhouse’s acclaim continued on an upward trajectory, and following the success of his Saint Eulalia in the Academy exhibition of 1885, he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy, one of only three promoted that year.[39][h]The other two elected as ARA that year were Henry Moore, known for his maritime paintings and Edward Burne-Jones.[39] This led to the Magazine of Art carrying an illustrated six-page profile written by James A. Blaikie, who considered that the technical attributes of Waterhouse’s work made it more appealing “to painters than to popular tastes”;[40] thereafter critics daubed Waterhouse as a painter’s painter.[39]

Illness and death

The brief death notice carried in The Times stated that Waterhouse had contended with a lengthy illness born with “great patience”.[41][i]This is in the short notice on p. 1, 12 February 1917;[42] an obituary appears on p. 6 in the same issue.[43] By 1913, he was displaying signs of ill health; a picture of him seated beside his work A Song of Springtime shows him appearing tired and haggard. Hobson describes another photograph of him from 1915, the first year he did not submit an exhibit to the Academy since 1890, as portraying him as “bent and frail, smoking the accustomed cigarette”.[44] The only time Waterhouse opted for a Christian theme for any of his Academy paintings was with The Annunciation in 1914; it marked the transition into his final collection of works when he focused entirely on events from medieval and Renaissance periods rather than myths.[45]

Waterhouse spent time at a hotel in Algeciras owned by Sir Alexander Henderson,[j]Later Lord Faringdon; together with later generations of the family, he purchased several of Waterhouse’s works and commissioned him to produce portraits of relatives.[46] possibly to recuperate in the favourable weather conditions.[47] He died on 10 February 1917 at his home, 10 Hall Road, St John’s Wood,[42] where he and his wife had lived since 1900;[48] the cause of death was “liver cancer, oedema of the extremities and heart failure.”[41] The funeral service took place on 15 February in the nearby Anglican Church; he is buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.[41]

Legacy

Wikimedia Commons

In the period leading up to his death Waterhouse was working on The Enchanted Garden; the painting remained unfinished but was displayed at the Royal Academy exhibition that year as a token of respect by his counterparts.[49] Three other items of his work were also included: Miranda;[k]This version of Miranda was noted as missing by Hobson in 1989; it is not Miranda – The Tempest and was around half the size of that painting.[50] Fair Rosamund; and Tristan and Isolde.[50] By 1917, Victorian painters had fallen out of fashion, and the vigour of the First World War was increasing, so no individual memorial exhibition was ever staged; thirteen of his works were however among those displayed as part of the commemoration exhibition “Works by Recently Deceased Members of the Royal Academy” held in 1922.[51]

Gallery

Notes

| a | Waterhouse’s exact date of birth is uncertain; an Italian birth certificate, which has since been mislaid, gave a date of 6 April but church records indicate that as the date of his baptism, a service not normally undertaken immediately a child is born.[5] The birth date on Waterhouse’s gravestone is now illegible, but Trippi notes that R.J.T.Cartwright saw the gravestone in the 1970s before it deteriorated and it displayed 16 January.[6] In his publications of 1980 and 1989 about Waterhouse, Hobson quotes 6 April 1849 as the date of birth.[7][8] |

|---|---|

| b | The nickname is a diminutive for Giovannino (Little John).[5] |

| c | The four Waterhouse children were: John William; Edwin, baptised in 1850; Jessie, born in 1853; and Charles, their only child born in England, baptised in 1856.[15] |

| d | Now the Victoria and Albert Museum.[19] |

| e | Pickersgill held the office of Keeper at the Royal Academy from 1873 until 1887.[22] |

| f | Trippi suggests that, despite the couple opting to be married in a Church of England, Waterhouse’s captivation with ritual magic as subjects reflects an interest in the occult.[25] |

| g | Or maenad |

| h | The other two elected as ARA that year were Henry Moore, known for his maritime paintings and Edward Burne-Jones.[39] |

| i | This is in the short notice on p. 1, 12 February 1917;[42] an obituary appears on p. 6 in the same issue.[43] |

| j | Later Lord Faringdon; together with later generations of the family, he purchased several of Waterhouse’s works and commissioned him to produce portraits of relatives.[46] |

| k | This version of Miranda was noted as missing by Hobson in 1989; it is not Miranda – The Tempest and was around half the size of that painting.[50] |

References

- p. 4

- p. ix

- p. 9

- p. 238

- p. 11

- p. 11

- p. 10

- p. 11

- p. 226

- pp. 11–12

- p. 12

- pp. 11, 12

- p. 14

- pp. 12, 13

- p. 2

- p. 14

- p. 15

- pp. 16–17

- p. 17

- p. 31

- p. 16

- p. 56

- p. 57

- p. 111

- p. 28

- p. 15

- p. 179

- p. 29

- p. 33

- p. 31

- pp. 35–36

- pp. 33–34

- p. 33

- p. 37

- p. 69

- p. 1

- p. 229

- p. 101

- p. 216

- p. 113

- p. 137

- p. 20

- p. 117

- p. 116

- p. 122