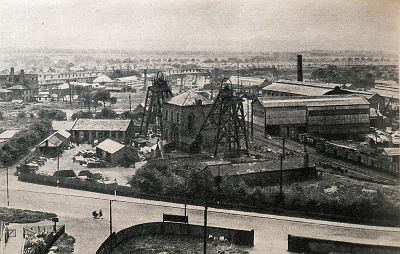

Ellesmere Colliery in Walkden on the Lancashire CoalfieldThe Lancashire and Cheshire Coalfield in North West England was one of the most important British coalfields. Its coal seams were formed from the vegetation of tropical swampy forests in the Carboniferous period more than 300 million years ago. was sunk in 1865 by the Bridgewater Trustees. The colliery was south of Manchester Road and north of the Manchester and Bolton Railway in the town centre. Two shafts were sunk to access the Doe, Five Quarters and Trencherbrook mines,[a]In Lancashire a coal seam is referred to as a mine and the coal mine as a colliery or pit. and the Navigable LevelExtensive network of underground canals that drained the Duke of Bridgewater's coal pits emerge into the open at the Delph in Worsley, Greater Manchester..[b]The Duke of Bridgewater’s underground canal system

Coal had been mined in the area for centuries, and the colliery was sunk to access coal at deeper levels. At different times over the life of the colliery, coal was moved by canal, road and rail. Production ended in 1923, but the shafts were retained for pumping, ventilation and access to the underground canal system until 1968.

Background

Small-scale coal mining had been carried on from the Middle Ages where coal seams outcropped in Worsley and the surrounding area of the Manchester CoalfieldPart of the Lancashire Coalfield. Some easily accessible seams were worked on a small scale from the Middle Ages, and extensively from the beginning of the Industrial Revolution until the last quarter of the 20th century.. Scroop Egerton, 1st Duke of Bridgewater, inherited the Worsley estate in 1730.[1] After inheriting the estate in 1748 the 3rd Duke was keen to exploit the coal under his largely agricultural estate, but the coal pits he inherited were small and particularly wet from water that percolated through porous sandstone above the coal. The water problem was solved by driving an underground level or canal that intersected the coal seams northwards towards Walkden from the rock face of an old quarry at Worsley Delph.[c]The Bridgewater Canal starts where the Navigable Levels exit the rock face at the Delph The level served three purposes; it drained the coal workings, provided a means of transporting coal out of the mines directly to the Bridgewater Canal which it also kept in water.[2]

The Navigable Levels were developed into an extensive system of underground canals branching from the original level. The mine workings were also accessed by shafts sunk along the main drainage level, providing access for colliers and materials and coal was transported underground directly to the Bridgewater Canal for onward shipment. The first pits to be linked included Wood Pit, Ingles Pit and Kempnough Pit in Worsley, Edge Fold Pits and Magnall’s Pit in Walkden.[3]

History

Ellesmere Colliery on Manchester Road, Walkden, was sunk adjacent to the main Navigable Level in 1865 by the Bridgewater TrusteesCoal mining company on the Lancashire Coalfield with headquarters in Walkden near Manchester., who owned the mineral rights in Worsley and Walkden. Its shafts were deeper than the nearby, older workings of the Causewayside Pits that were abandoned when Ellesmere was sunk. Ellesmere’s shafts accessed deeper seams than had previously been possible from the Navigable Level. A Fan Pit[d]ventilation shaft was started north of Ellesmere in 1867 and was linked to Ellesmere’s shafts in 1870. The first coal was boated down the the Level in 1870. Ellesmere was also linked Ashton’s Field Colliery and other pits to the north.[4] Coal could be moved from Ellesmere by canal, road and rail.[5] After 1887 the Level was no longer used to transport coal, but continued in use as a giant sough to drain the workings of the Bridgewater pits until Mosley Common Colliery closed in 1968.[6]

Ellesmere No. 1 Pit was 12 feet (4 m) in diameter, 276 yards (252 m) deep and had timber headgear. No. 2 Pit, also 12 feet in diameter with timber headgear, was 415 yards (379 m) deep. They accessed the Doe, Five Quarters and Trencherbone mines. Between the shafts was the square engine house, where a pair of Naysmith Wilson 175 hp steam winding engines with 30-inch by 54-inch cylinders were installed in 1866.[7]

Coal was wound to the surface in cages. Wire ropes were used on the winding gear and in the 1880s Ormerod detaching hooksEnglish mining engineer and inventor who worked at Gibfield Colliery in Atherton, Lancashire where he devised and tested his safety device, the Ormerod safety link or detaching hook. provided protection against overwinding. Coal was cut by hand by hewers, who performed the most dangerous tasks, undercutting the seam of coal before it “dropped”.[8] Candles were used into the 1870s; safety lamps were only used when testing for gasDamps is a collective name given to all gases other than air found in coal mines in Great Britain. The chief pollutants are carbon dioxide and methane, known as blackdamp and firedamp respectively. before the shift started.[9]

By 1900, No. 2 Pit had steel lattice headgear and the pit was working the Five Quarters, Seven Feet, Black, Doe, Trencherbone and Cannel mines. The pit had 870 coal tubs, 300 safety lamps and its surface plant was powered by four Lancashire boilers. The coal was readied for sale using four vibrating screens and 78 feet long picking belts. The Fan Pit had a Sirocco-type ventilation fan.[10] In 1923 shortly before coal production ceased, the colliery employed 401 underground and 400 surface workers.[11] Coal production ended in the 1923, but the shafts were retained for pumping, ventilation and access to the underground system until 1968.[6]

Notes

| a | In Lancashire a coal seam is referred to as a mine and the coal mine as a colliery or pit. |

|---|---|

| b | The Duke of Bridgewater’s underground canal system |

| c | The Bridgewater Canal starts where the Navigable Levels exit the rock face at the Delph |

| d | ventilation shaft |