Matthew Murray (1765 – 20 February 1826), an engineer born in Newcastle on Tyne, became known for building and improving steam engines. He built the world’s first commercially successful steam locomotive and a marine engine in 1812. After being apprenticed to a blacksmith and millwright in Stockton-on-Tees, Murray worked with steam engines and flax-spinning machinery before seeking work with John Marshall in Adel, Leeds.

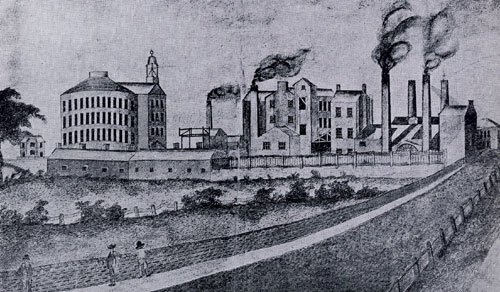

After setting up a new flax-spinning factory for Marshall in Holbeck, Murray went into business with partners who built the Round FoundryEngineering works off Water Lane in Holbeck, Leeds in Yorkshire, built for Fenton, Murray and Wood. in Holbeck, Leeds. Despite industrial espionage and attempts by rivals Boulton and Watt to discredit him, his pioneering engineering business thrived and manufactured the first machine tools, hydraulic testing machines, steam engines for factories, engines for steamboats. and the first commercially successful steam locomotive, Salamanca Salamanca, designed and built by Matthew Murray in 1812, was the world’s first commercially successful steam locomotive., for the Middleton Railway.

Salamanca, designed and built by Matthew Murray in 1812, was the world’s first commercially successful steam locomotive., for the Middleton Railway.

Early Life

Matthew Murray was born in Newcastle on Tyne in 1765, but little is known of his family or early life. After leaving school at 14, he was apprenticed to a blacksmith and millwright. Few children were educated until 14, so his parents must have had the means to do so. Murray probably gained experience of the Newcomen engines that operated in the area. In 1785 he ended his apprenticeship.[1]

Murray married Mary Thompson of Wickham in 1785. They moved to Stockton-on-Tees the following year, where Murray found work as a journeyman mechanic.[2]

Career

Flax spinning was important in the Darlington area, and mechanics from Stockton did most of the millwrighting. Murray made and repaired machines for Kendrow and Porthouse, who were the first to use power-driven machinery for spinning flax.[3]

In 1788 trade in flax was slack in Darlington, and so Murray set off to look for work at Scotland Mill, a water-driven flax mill in Adel near Leeds owned by John Marshall. Murray was engaged and put in charge of the machinery. He made improvements and Marshall, recognising his talent, gave him £20, a considerable sum that enabled his wife and family to join him to live in a cottage on Black Moor at Adel.[2]

Holbeck

Murray developed and improved the flax-spinning machinery, and when Marshall built a new mill in Holbeck, Murray set up the machinery and installed the spinning machines he had designed and patented in 1790. The mill was powered by a steam engine that lifted water from the Hol Beck to power a water wheel.[4] The steam engine was replaced by a Watt engine that drove 900 spindles in 1793. That year Murray took out a patent for “Instruments and Machines for Spinning Fibrous Materials, etc”. It included a carding engine and new process, wet spinning, which enabled finer yarns to be spun, revolutionising linen manufacture.[4][5]

Round Foundry

Main article: Round FoundryEngineering works off Water Lane in Holbeck, Leeds in Yorkshire, built for Fenton, Murray and Wood.

Engineers were in demand in Leeds, and in 1795 Murray left Marshall to set up in business with David Wood at a foundry at Mill Green, where they made flax-spinning machinery. James Fenton, and for a time William Lister, joined the firm; in 1802 they built the Round Foundry in Water Lane, Holbeck in Leeds.[4] The site was near the Aire and Calder Navigation,[6] where, in one of the world’s first integrated engineering works, Murray made his name and fortune.[7]

Murray’s first steam engine in 1799 attracted the attention of Boulton and Watt of Birmingham, who sent William Murdoch and Abraham Storey, as spies, to visit the works of the unsuspecting Murray. Murdoch and Storey were made welcome and given information about engine designs. Boulton and Watt incorporated the ideas into their own engines, and considered buying land next to Murray’s works to prevent his company expanding. When Murray paid a reciprocal visit to Boulton and Watt’s Soho Works he was turned away.[3]

Boulton and Watt successfully challenged two patents Murray had taken out in the courts. His patent for improved air pumps and other innovations in 1801, and one for a self-contained compact engine with a new type of slide valve in 1802, were contested and overturned. Murray had made the mistake of including too many improvements together in one patent so that if any single improvement was found to have infringed copyright, the whole patent was invalidated.[8] Nevertheless Fenton, Murray and Wood became serious rivals to Boulton and Watt, whose action to discredit Murray failed, and the Round Foundry thrived.[9] The firm attracted many orders across the field of engineering, including dye house, improved hydraulic presses for baling cloth, the first machine tools, and designed hydraulic testing machines, made steam engines for factories and textile machinery at the Round Foundry. In 1809 the Royal Society awarded Murray a gold medal for his flax-heckling machine.[10] He improved steam-engine design, including the three-port slide valve. In 1812 he built the first commercial steam locomotive, Salamanca, for Charles Brandling, owner of the Middleton Colliery. It ran on a rack railway designed by John BlenkinsopMining engineer at Charles Brandling’s Middleton Collieries who patented a rack and pinion system for a steam locomotive and commissioned the first practical railway locomotive from Fenton, Murray and Wood’s Round Foundry in Holbeck, Leeds in 1811., Brandling’s agent at the Middleon Collieries. On 27 June 1812 the engine hauled 27 waggons weighing 94 tons at 3½ miles per hour from Hunslet Moor to the coal staithe on the riverside.[11]

Around the same time the locomotive was being built, John Wright of Yarmouth ordered a high-pressure steam engine to power L’Actif, a captured French privateer that he had bought from the government. The 52-foot (16 m) long boat was taken to Leeds, where Murray installed the steam engine and paddle wheels. The boat was renamed Experimental before returning under steam to Yarmouth, where she went into revenue-earning service.[12]

In 1816 Murray built two large twin-cylinder marine steam engines for Francis B. Ogden, the first person to operate a regular paddle-steamer service on the Mississippi. Ogden patented the design as his own in America, where it was widely copied for Mississippi paddle steamers.[10] Murray’s last major work was a hydraulic press for testing chain cables for the Navy Board. The 34-foot (10 m) long press could exert a force of 1,000 tons, and was the model for hundreds of others.[10]

Family and legacy

Murray married Mary Thompson of Wickham in County Durham in 1785. They had three daughters and a son, Matthew.[2] After 1802, Murray lived at Holbeck Lodge which he built close to the foundry. It was usually known as Steam Hall, because it was one of the first houses to have steam heating.[4] In a Luddite riot in 1812, a group of rioters outside the house threatened to break the machinery in the works, but in the absence of Murray, were confronted by his wife who fired a pistol and the crowd dispersed.[13]

Murray’s son served his apprenticeship at the Round Foundry, and founded an engineering business in Moscow. His daughter Margaret married engineer Richard Jackson, who succeeded Murray at the Round Foundry when the company was renamed Fenton, Murray and Jackson.[14]

Murray died on 20 February 1826 and was buried in St Matthew’s churchyard in Holbeck; a cast-iron obelisk made at the Round Foundry marks his grave.[14] His firm survived until 1843. Several notable engineers trained there, including Benjamin Hick, Charles Todd, David Joy and Richard Peacock.[14]