“The Rajah’s Treasure” is a short story by the English author H. G. Wells (1866–1946) first published in Pearson’s MagazineMonthly publication founded by Cyril Arthur Pearson, published 1896–1939, the first British periodical to include a crossword. in July 1896 and subsequently in Thirty Strange StoriesCollection of 30 short stories by H. G. Wells, first published in 1897. (1897). Wells later rewrote the story under the title “The Spoils of Mr. Blandish”,[1] in which form it appeared in Boon (1915), purported to be a collection of humorous and satirical essays by the distinguished novelist George Boon, but written by Wells himself.[2]

Told as a third-person narrative, it concerns a rajah who is rumoured to have amassed great wealth and is murdered by his heir, who discovers that the treasure he has inherited is not what he had expected.

Synopsis

The rajah has transformed the village of Mindapore, on the slopes of the Himalays between Jehun and Bimabur, into a prosperous fortified city. Rumours begin to spread that he is creating a hoard of rubies, gold ornaments, pearls, diamonds from Golconda, and all manner of other precious stones. One day an Englishman visits the rajah, and is seen to take gold away with him when he leaves. Those closest to the rajah suspect that the Englishman, later revealed to be MacTurk, must be a dealer in diamonds or rubies, and one remarks that since his visit the rajah has been rather secretive, hiding something in his robe: “Rubies! What else can it be?” says the chief minister Golam Sha

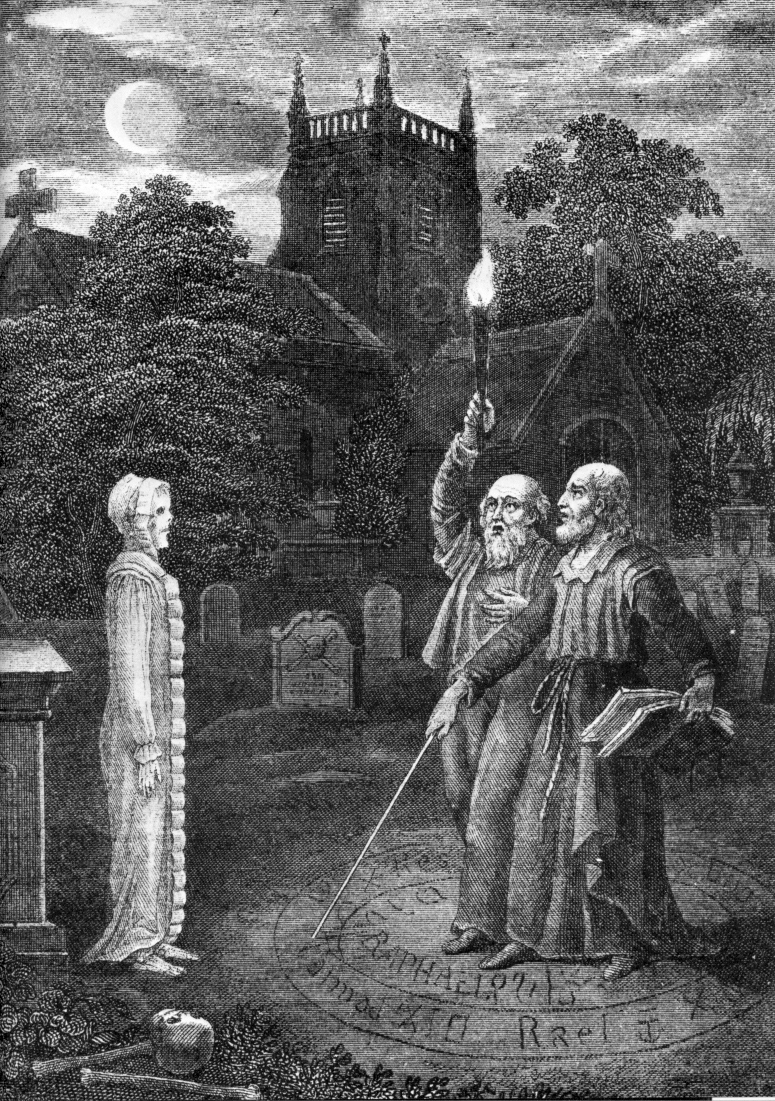

One day a huge safe is delivered to the rajah’s palace, said to have been built by necromancers

Form of magic in which the dead are re-animated and able to communicate with the sorcerer who invoked them, just as they would if they were alive. in England and to have a magic lock, which could be opened only by a word known to the rajah and a little key hung around his neck. At least once every day the rajah visits the safe in the little room where it is installed, returning with brighter eyes. “He goes to count his treasure,” concludes Golam Shah.

Those around the rajah begin to notice changes in his appearance and behaviour; he seems to be becoming enfeebled, stumbling as he leaves his treasure room with his turban askew, and his memory becomes “curiously defective”. Azim Khan, the rajah’s heir, encourages the disaffected soldiers – who have not been paid despite the rajah’s supposed hoard – to mount a coup, during which the rajah is shot dead. But the rioters are unable to open the safe.

Eventually the British deputy-commissioner takes charge of the situation.[a]India was under British rule from 1858 until 1947. He has the manufacturer of the safe, Chobbs, give instructions to an engineer as to how to open it, which he succeeds in doing. But what the engineer discovers is not a hoard of jewels but “undreds” of broken whiskey bottles. MacTurk reveals that he had introduced the rajah to Bourbon whiskey, but because of strict Islamic laws against the consumption of alcohol the rajah had become a secret drinker, and had ordered the safe from MacTurk as a store for his bottles of whiskey. When it had got too full, the rajah had smashed the empty bottles to make more space.

See also

- H. G. Wells bibliographyList of publications written by H. G. Wells during the more than fifty years of his literary career.